From the margins, a voice remembered

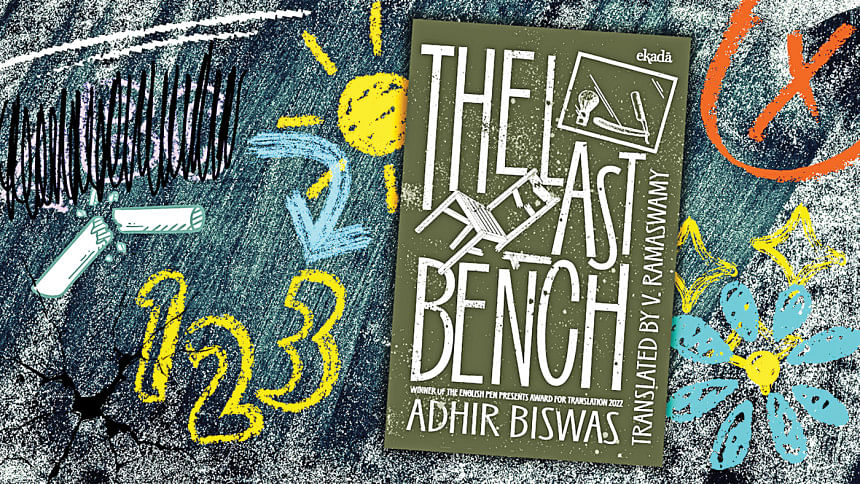

In The Last Bench, Adhir Biswas returns to the landscapes of his childhood with the tenderness of a son and the precision of a chronicler. This deeply moving memoir, translated masterfully by V. Ramaswamy, is at once an act of remembrance and resistance, a testimony to growing up Dalit, poor, and displaced in post-Partition India.

Born in 1955 in Magura (now in Bangladesh), Biswas was 12 years-old when his family migrated to Calcutta in 1967, carrying with them little more than loss. For a Bangladeshi reader, this journey from the familiar rhythms of East Pakistan to the hostile margins of Indian society evokes not just Partition, but the continuing exile and erasure many refugees experience in the subcontinent. But The Last Bench is not just a refugee story. It is an intimate portrait of caste, class, and childhood told with searing honesty and lyrical restraint.

At the heart of the memoir is the figure of the young boy, Biswas himself, made invisible in a world structured to exclude him. School becomes the starkest symbol of this exclusion. He is relegated to the literal last bench, isolated and humiliated, his cracked slate and wet rag a silent protest against poverty and prejudice. These classrooms, which should have been spaces of learning and liberation, are instead sites of cruelty with social hierarchies mapped neatly onto seating arrangements and classroom silence.

Yet Biswas's prose does not dwell in bitterness. It is illuminated by affection for his ailing mother, with whom he shares quiet, wonder-filled journeys into the forest; for Bhombol, the loyal dog who becomes his companion after her death; and even, in moments, for the father who pins all his desperate hopes on him, his youngest son. There is grief, but also a defiant love that sustains the boy through hunger, ridicule, and loss.

What elevates The Last Bench beyond memoir is Biswas's unflinching gaze at caste oppression in Bengal, an aspect often conveniently omitted from mainstream narratives. The notion that caste discrimination is a southern or rural issue is powerfully dismantled here. In a state that prides itself on intellectualism and egalitarian ideals, Biswas exposes how caste continues to determine access, dignity, and voice. His father's humble profession as a barber not only defines the family's economic standing but also their social visibility or lack thereof.

The narrative unfolds with sensory richness: the aroma of the weekly market, the oppressive heat of tin-roofed schoolrooms, the silent companionship of a dog's footsteps. Ramaswamy's translation preserves these textures with fidelity and grace, ensuring that the reader never feels detached from the Bengali or rural idioms that shape Biswas's world. There's a humility in the language that mirrors the boy's own life accompanied with a quiet, stripped-down prose that reveals just enough without veering into sentimentality.

Biswas's prose does not dwell in bitterness. It is illuminated by affection for his ailing mother, with whom he shares quiet, wonder-filled journeys into the forest.

For readers, The Last Bench also serves as a mirror into a shared, fragmented past. Biswas's memories of Magura are lush, intimate, filled with ancestral echoes. They remind us that the wounds of Partition are still tender. His return to that lost land is not nostalgic but aching. It asks: What do we carry when we lose home? What parts of us remain rooted even after the soil beneath our feet has changed?

The title itself is layered with meaning. The last bench is not just a place in the classroom. It becomes a metaphor for marginality, for a childhood spent in the shadows of both history and hierarchy. But it is also from this place of invisibility that Biswas emerges as one of Bengal's foremost Dalit voices, a writer and publisher who has made it his life's work to speak for those still seated at the back, unseen and unheard.

The Last Bench is essential reading, not only as a memoir of a refugee child, or a Dalit writer, but as a fierce and beautiful act of memory. In recounting his personal struggles, Biswas tells a much larger story, that of migration, caste, belonging, and survival. It is a story we in Bangladesh too often forget we are part of.

This is a voice that has waited too long to be heard.

Namrata is a literary consultant, columnist, and podcast host.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments