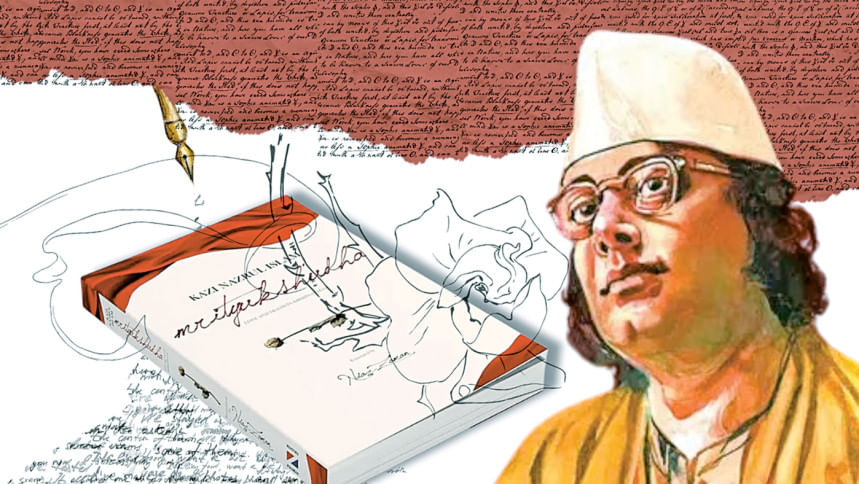

The bard of love and rebellion in prose

Being a musician who grew up singing and listening to Kazi Nazrul Islam's songs, I was quite familiar with his writing, particularly his diction, figures of speech, and sundry themes. His musical oeuvre includes a vast array of music genres, including ghazal, thumri, khayal, qawwali, kirtan, and many more, which likewise address diverse subject matters. He created mellifluous lyrical songs that delineate passionate love while composing robust protest songs reflecting his rebellious zeal, side by side. He indeed had a "war bugle" in one hand and a "tender flute" in another, as he famously said in his poem "The Rebel" (1922).

One might wonder why I began with his songs and poems while writing a review of his novel. One reason to start with this discussion is to emphasise how skillfully Nazrul weaves together all these diverse themes, ideas, and beliefs into this short novel Mrityukshudha, which his songs and poems, across different genres, present separately. He depicts a rebel imbued with Marxist zeal who seeks to raise national consciousness among the poor to fight for their rights and a woman who embarks on a challenging journey to create her identity and change her fate through education and religious conversion, all while narrating a love story that challenges the prevailing societal rules and regulations. He concisely intertwines the themes of nationalism, plight of the subalterns—especially the women and their different mechanisms of survival and small-scale resistance, divisions within people of different religious views and how religion can be used as an oppressive apparatus to manipulate and exploit the sufferers even more and not to mention, love and how societal restrictions may intervene in such a powerful affect.

Another reason I began with this comparative discussion is to highlight how wonderfully poetic the language of Mrityukshudha appeared to me, ornamented with his signature literary devices and phraseologies. This brings to mind renowned Romantic poet William Wordsworth's argument in "Preface to the Lyrical Ballads 1800" where he postulates that one cannot differentiate between the language of a good poem and good prose. This idea constantly flashed through my mind while reading the novel. Particularly, Nazrul's preoccupation with similes and metaphors involving natural elements, a common feature in his songs and poems, recurs in his depiction of various characters, settings, and incidents throughout the novel. Furthermore, his incorporation of songs from time to time adds another layer of poetic essence to this novel.

Although the novel is simply structured with 28 chapters, it contains a subtle, intriguing division. The story begins with a family in Krishnanagar, struggling with extreme poverty as they literally die of hunger. Three unnamed daughters-in-law live with their children, the mother-in-law, and Paykale, the only surviving son of the mother-in-law. The first half of the novel highlights the intensity of their poverty and suffering. The second half introduces another family: Latifa and her fugitive brother, Ansar. Ruby, a widow and Ansar's love interest, is also introduced in this part. This section focuses on Ansar's revolutionary activities and Mejo Bou's efforts to change her destiny. She converts to Christianity after being shunned by her community for receiving education from Christian missionaries. Later, she reconverts to Islam as her son dies, and she needs to feed the children in the 40-day rite. Meanwhile, Ansar is imprisoned. The novel ends with Mejo Bou's vision of educating the village children and Ansar's final days of amorous love with Ruby, who comes to look after him breaking all the social boundaries and prejudices.

Interestingly, Ansar does not appear in the novel until chapter 15. After his dramatic entrance, Mejo Bou's new identity as an educated Christian woman named Helen is revealed. This subtle division within the plot symbolically showcases that change and revolution become inevitable when exploitation reaches its zenith.

Interestingly, Ansar does not appear in the novel until chapter 15. After his dramatic entrance, Mejo Bou's new identity as an educated Christian woman named Helen is revealed. This subtle division within the plot symbolically showcases that change and revolution become inevitable when exploitation reaches its zenith. Ansar emerges as a messiah of humanity, under whose influence, voiceless people dare to speak. Ansar's emergence and his death, hence, appear as a deft structural design in the novel.

Published in 1930, a turbulent time in world history, Nazrul's narrative captures the zeitgeist of that period. He includes direct and indirect references to significant events of that time, such as the Russian Bolshevik Revolution, the national resistance movement against the British in India, and Gandhi's non-cooperation movement. However, what struck me most is how predominantly it is about Muslim people and their culture. This is remarkable because when he was writing, Muslim representation, especially of the lower social strata, was rare in the Bengali literary canon. Nevertheless, he does not do so to elevate any religion over others; rather, he seems to criticise any religious venture that exploits people. The incidents of Maulana pushing the impoverished family of Mejo Bou to further poverty by suggesting they sell all their goats and contribute 15 rupees as penance for Mejo Bou's conversion, or Mejo Bou's feeling of being shackled by new ties despite adopting an educated identity as Helen after conversion, reflect Nazrul's stance against manipulative religious manoeuvres. After all, Nazrul is known as a writer of humanity who believes in the emancipation of people from all forms of restriction and exploitation by those in power, whether social, religious, or political.

One cannot finish reading this translated novel without feeling profound gratitude towards the translator, Dr Niaz Zaman; there is no doubt that Nazrul's writing is complex. Moreover, he uses local people's dialects so authentically that sometimes the general people of Bengal might miss the overt and covert meanings. Zaman translates those difficult words, phrases, and even slang with lucidity. Additionally, she includes footnotes to help readers understand the cultural and historical context of Bengal at that time. She has definitely made a significant contribution, not only to the Bangladeshi literary canon but also to world literature. Although Nazrul is a powerful revolutionary writer who seamlessly blends love and revolution in his work, he remains largely unknown worldwide. It is now an intellectual responsibility to celebrate his writing both locally and globally as much as possible.

Moumita Haque Shenjutee is Lecturer, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments