The world of Abdus Shakoor's paintings

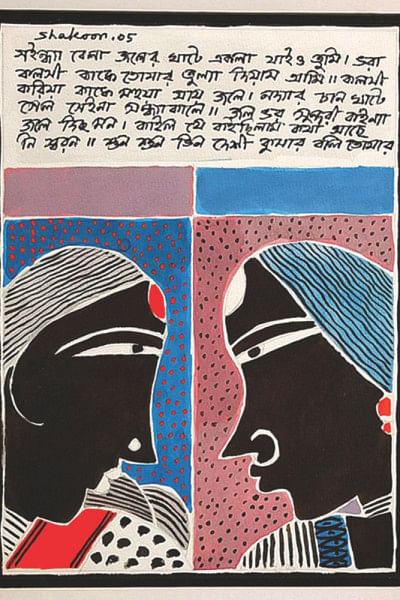

Last year, a handful of watercolour paintings of Abdus Shakoor Shah, along with a few selected works of two other artists from Bangladesh were put in an exhibition in a gallery in Tokyo, under the title “Three poems from Bangladesh”. The title was especially apt for Shakoor's paintings, since they display some of the qualities that one looks for in a poem- an inner rhythm, a neat composition, imagery, movement, and above all, a theme. In spite of these similarities, however, his paintings insist on an identity of their own, which is not difficult to recognize. Shakoor's works are known for their complex forms that engage his ideas in a dialectical exploration of metaphors, nuances and meaning. What it means for Shakoor is that he is constantly experimenting with newer modes of expression, since an ideal form remains forever in the realm of possibilities. His works display a combination of different expressive modes, sometimes complex, subtle or difficult, sometimes disarmingly simple. But nowhere he is naive, or labored. There is a feeling of naturalness in their composition, as they relate to the world of our experience, and take their strength from our feelings and emotions.

A Retrospective of Abdus Shakoor's works is currently on at the capital's Shilpangan Gallery, and will be open till May 15 from 12-8pm.

Shakoor's sketches fall in the category of the simple - where the form is easily reconcilable with the content, and the content is lifted from reality as we experience it. In terms of the composition, these sketches retain only the bare essentials, sometimes employing just a brief line to cover for a whole figure. Yet, there is no doubt about what they want to express, and what they aspire to.

The sketches have a recognisable content- they talk about the problems of man and society from the perspective of a struggling, developing country. Shakoor has been drawing these sketches with the same theme from 1976, although the very recent ones are presented here. There are free drawings where lines are simple but robust, and their interconnected patterns infuse a dynamism into the composition. Shakoor's favorite mode is pen and ink. Many of the sketches have bare outlines that convey the meaning with scant details, relying on a suggestiveness that leaves much of the space empty. But there are other sketches where the space is heavily worked over until a contrast is achieved between the white and black surfaces. This contrast is important to understand the symbolism of his sketches - they deal with contrasts that characterize our life- not simply the ones between the social classes or between one's expectation and achievement in everyday life, but deeper, more confusing ones between dreams and reality, between feelings of alienation and the sense of belonging that the family or the society wants to provide to the individual. It is interesting to see how the contrast within a monochromatic surface is extended to the way Shakoor uses light and shade, their interplay as well as their separate spheres of operation.

Shakoor's sketches are informed by a deep commitment he feels to humanity. He evokes, often wistfully, the forces of change in his works, which can eventually display dislodge the monolithic social structures. He draws his inspiration from progressive ideologies, which also provide him with the set of symbols he works within these sketches. One notices the ubiquitous kerosene lamp and hurricane lantern symbols of a developing country's poverty, struggle, as well as hope. There are broken windows and doors, suggesting the need for pulling down oppressive social machines. But in spite of the strident optimism that, at times, gives his sketches a rough edge, there is a genuine human touch in Shakoor's world. His people are linked to each other in a bond of togetherness, care and concern. His human figures and animals share the same space in an affectionate understanding of each other. His dogs are almost human in their insistence in carving out a space where love and affection will be prime factors.

The writer is an academic, novelist and critic. He is a professor at Department of English, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments