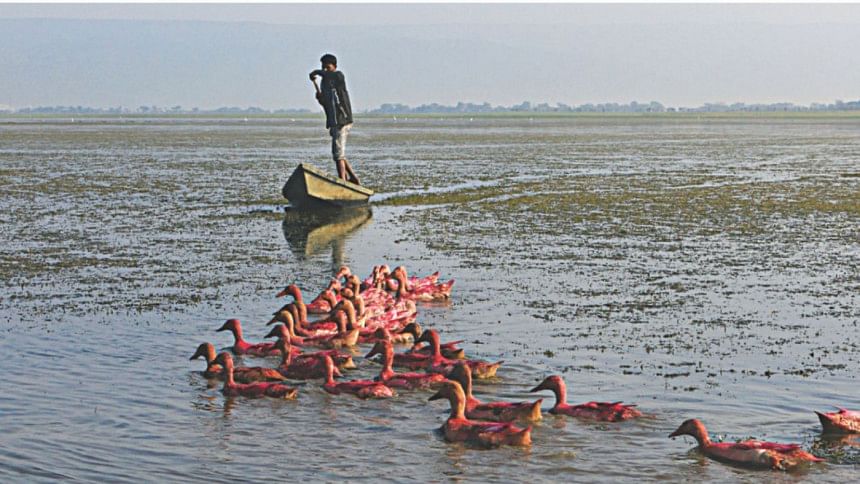

Is a new vision possible for Tanguar Haor?

Over the last 50 years, Bangladesh's journey towards community development has essentially been a result of government, donors, and NGOs coming together to work for the vulnerable people. But how do we capture our experience of community development and use it in follow up projects? Do we only rely on what donors tell us to do in every new project, forgetting what we did before? Is our organisational community development knowledge shareable or do we keep such knowledge within the organisation as "trade secrets"?

Experiences and lessons from numerous community development projects of our government and NGOs are rarely made public. Between 2010 and May 2021, for example, the Bangladesh Climate Change Trust Fund (BCCTF) supported 789 projects, implemented by different government agencies and NGOs. But how many project documents are available on the BCCTF website? None.

There are, of course, exceptions. For example, the Department of Environment (DoE) of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) implemented a project between 2010 and 2015 called "Community Based Adaptation in the Ecologically Critical Areas through Biodiversity Conservation and Social Protection Project" (CBA-ECA Project) with NGOs and supported by the BCCTF, the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Near the end of the CBA-ECA Project, the DoE collaborated with IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Bangladesh to capture the experiences of community development and resilience building in the Ecologically Critical Areas (ECAs) within the haor (wetland) and coastal regions. This collaboration brought out a fantastic book titled, "Community Based Ecosystem Conservation and Adaptation in Ecologically Critical Areas of Bangladesh".

Talking about the government's community development initiatives through natural resource management, in December 2006, the MoEFCC started collaborating with the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and IUCN to improve the dire condition of Tanguar Haor in Sunamganj. Since the 1930s, this freshwater wetland was overexploited for fisheries through leasing and other unsustainable practices by local elites, and to some extent by haor dwellers, with the government's policy and administrative support. Given its poor condition, Tanguar Haor was declared an ECA in 1999. In the following year, it was declared a Ramsar Site, under the Ramsar Convention, because of its globally important migratory birds.

In 2001, the land ministry handed over Tanguar Haor to the MoEFCC and the leasing was stopped. This landmark transfer opened the door to sustainable management of the haor with its people and resulted in the SDC-supported "Community-based Sustainable Management of Tanguar Haor Project". During 2006-2016, IUCN Bangladesh and its NGO partners implemented this project on behalf of the MoEFCC. Major achievements of this 10-year project included giving back the right to fish to the local community through permit fishing and benefit-sharing mechanism gazetted by the government, a three-tier inclusive governance system (from village to the central level) to participatory management of the wetland, restoration and protection of wetland resources and biodiversity, and overall community empowerment and livelihoods improvement. In 2016, "Tanguar Haor: A Decade-long Conservation Journey" by IUCN Bangladesh captured this 10-year experience.

After the end of SDC funding, the MoEFCC used government allocations to implement a two-year-long Bridging Phase project in Tanguar Haor. It was an unprecedented but welcome move from the MoEFCC to collaborate directly with IUCN and NGO partners. This brief phase converted the community organisations into cooperatives, continued with fishing permits and benefit-sharing from fish harvests, and protected the haor's fisheries and other resources through community guards and local administration.

Since January 2019, Tanguar Haor does not have any "project" to manage it. But local communities, village and central cooperatives, and the local administration did continue—to some extent—several major systems put in place over the last 12 years.

On August 17, 2020, I wrote in this daily about the need for long-term support to the people of Tanguar Haor. UNDP Bangladesh has recently received funds from the Global Environment Facility (GEF) to design a comprehensive project with the MoEFCC titled, "Community-based Management of Tanguar Haor Wetland in Bangladesh". As per the Project Identification Form (PIF) available on the GEF website, the UNDP and the DoE would implement a five-year-long USD 21.6 million project—with the GEF providing USD 4.4 million and the remaining USD 17.2 million being co-financed by the MoEFCC (USD 12 million) and Ministries of Water Resources, Agriculture, and Fisheries (USD 5.2 million). This proposed financial arrangement reiterates the Bangladesh government's commitment to sustainably manage Tanguar Haor with the local people by ensuring coordination among relevant government agencies.

Although prepared in September 2020, the PIF of the new project could not sufficiently capitalise on the knowledge and lessons of the past Tanguar Haor projects (2006-2018) by consulting and appreciating IUCN Bangladesh's comprehensive book on Tanguar Haor (2016) and accomplishments of the MoEFCC's Bridging Phase project (2017-2018).

A significant focus of the new Tanguar Haor project will be implementation of the "Ecologically Critical Area Management Rules, 2016" (ECA Rules) of Bangladesh. This is a logical approach since the long-anticipated ECA Rules are now available to be implemented in ECAs and the new project's implementing partner DoE is responsible for improving all 13 ECAs, including Tanguar Haor.

Many proposed activities of the anticipated project are broadly similar to what were done by the MoEFCC, IUCN and its partners for over 12 years, such as participatory wetland resource management, related frameworks and governance structures, biodiversity conservation, and livelihoods opportunity creation. There are also many new, timely activities expected to be included in the new project, for example, creating sustainable financial mechanism (including public-private partnerships), giving special focus to Covid-affected families, enhancing private-community partnerships, controlling pollution, addressing emergence of new diseases from damaged ecosystems, and establishing an ecological monitoring system.

The new Tanguar Haor project will indeed reflect the mandates and priorities of the DoE, UNDP, and GEF, and their past experiences in similar ecosystems. But the project development team of UNDP need to consider three crucial aspects while designing the new project. First, the wealth of experience and knowledge captured by MoEFCC, IUCN and partners during 2006-2018 should be duly considered by closely interacting with these agencies and individuals involved. The lessons from past projects on co-management structures, benefit-sharing mechanisms, resource protection measures, and community-based organisation management, for example, need to be appreciated. Second, based on the above lessons and the changes taking place in the absence of any projects over the last 30 months, DoE and UNDP can then align their new approaches with the existing best practices and new challenges and opportunities. In this way, Tanguar Haor can avoid being an experimental ground of new management structures, again and again. Third, both the DoE and UNDP are committed to implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). In October 2021, the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP) of the CBD is expected to decide on the next global conservation targets for the coming decade and beyond. The new Tanguar Haor project thus has an amazing opportunity to appreciate these new targets and become the first project of the new era.

Dr Haseeb Md Irfanullah is an independent consultant working on environment, climate change, and research systems. His Twitter handle is @hmirfanullah.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments