Jibanananda Das: Tropes, Tensions, Tendencies

Today—February 17—marks the 123rd birth anniversary of Jibanananda Das (1899-1954), recognised today as one of the greatest Bengali poets of all time. But he was quite neglected during his lifetime. Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) did not take Jibanananda seriously at all. His first reaction to Jibanananda's poems was downright harsh and even gruffly dismissive, while his subsequent reaction was brief, curt, but favourable—inadequately, though—as he only spoke of the pleasure of looking at Jibanananda's poems, thereby pointing to the profusion and plenitude of visual images in his poetry. Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976) went to the extent of making fun of Jibanananda, saying something to this effect: For him, metaphor is more important than mother.

But then, it is true that both metaphors and images constitute and characterise the very power of Jibanananda's poetry, although he is much more than his tropological and metaphorical interventions and inventions as such.

But, among his notable contemporaries, it was only Buddhadeva Bose (1908-1974) who cared to read Jibanananda and evaluate his work to the extent that he could. Yet, I argue that his fondness for Jibanananda notwithstanding, Buddhadeva—remaining high on Western poetics and aesthetics, while characterising Jibanananda as the loneliest of poets—ultimately failed to do justice to his wide-ranging oeuvre that cannot be simply reduced to the themes of mere individual loneliness, alienation, and even existential crisis, although those themes are by no means absent in his work.

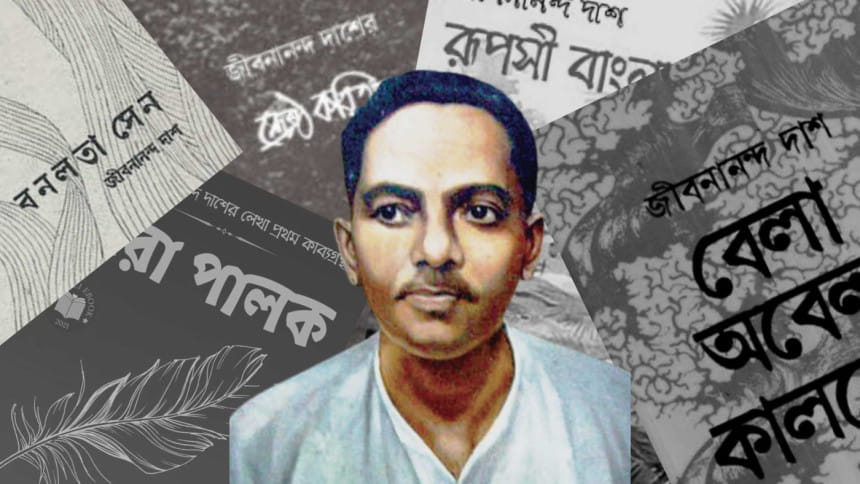

Jibanananda's first collection of poems, called Jhara Palak (Fallen Feathers), appeared in 1927. Then his second volume, Dhushar Pandulipi (Grey Manuscripts), came out in 1936, while the year 1942 saw the publication of one of his major works, Banalata Sen, a veritable tour de force. His other great collections such as Mahaprithibee (The Great World) and Satti Tarar Timir (The Darkness of Seven Stars) came out in 1944 and 1948, respectively. It was in 1954—the year of his death—that his Sreshtha Kabita (Best Poems) was published, and his posthumous collections such as Rupashi Bangla (Beautiful Bengal) and Bela Obela Kalbela (Time, Odd Time, Inauspicious Time) appeared in 1957 and 1961, respectively.

Indeed, Jibanananda Das's writing career spanned 35 years, from 1919 to 1954, during which he published a total of 269 poems in different magazines and journals. Of them, only 162 poems were collected in his seven volumes that I already mentioned. But, over a period of more than six decades following his death, Jibanananda's numerous poems, 28 novels, and more than a hundred stories—including his essays, letters, diaries, songs, even drawings and pencil sketches, as well as his massive "literary notes" of as many as 4,272 pages—were discovered. Thus, it's clear today that Jibanananda the poet was also an extraordinarily powerful short story writer and novelist as well as a thinker, among other things.

His novels—yet to be engaged adequately—were written between 1931 and 1948, and some of them include Purnima, Bibha, Karubasana, Jeebonpranalee, Pretinir Rupkatha, Mallyaban, Jalpaihati, Basmatir Upakkhyan and Sutirtha, experimentally structured and textured works of fiction that explore the complexities of the modes of becoming and being—as well as the limits of our language—differentially enmeshed as they all are in the tensions and transactions among the autobiographical, the psychological, the social, and even the political-economic, to say the least.

But, of course, Jibanananda Das—known as one of the major modernists in Bangla literature—was a poet in the first place. Today, critics and readers—invoking Western figures or approaches—find in Jibanananda such things as Keatsian sensuousness, Edgar Allan Poe's sense of the mysterious and even the macabre, Mallarméan symbolism, WB Yeats' sense of melancholy and death, the imagism of William Carlos Williams, and so on. The aesthetic of synaesthesia—or what I wish to call the "intersensory" experience that the great French poet Charles Baudelaire memorably embodies in his superb sonnet called Correspondences—is also at work in Jibanananda, as the critic Alakranjan Dasgupta pointed out once. And, then, a whole host of critics have found in Jibanananda certain elements of impressionism, abstract expressionism, Dadaism, surrealism, and even "postmodernism."

This list—by no means exhaustive—at least gives us an idea of the textual plasticity and hermeneutic hospitality of Jibanananda's extraordinarily rich poetic oeuvre, which, however, remains exemplarily rooted in his own land, Bangladesh—both urban and rural.

For instance, in his collection of incomparably beautiful sonnets called Rupashi Bangla alone, Jibanananda's massive constellations of images—soundless lights and silent surges of moist smells in the peasant's field, dewdrops drenching the chalta flowers, the brown-winged shalik growing cold in the shadows of the dusk, the Kadam forest under Ashwin's autumnal sky, spotted owls smelling like paddy fields, kingfishers iridescent in the sun, ripening mangoes, the stellar totality of the carambola, lemon tree branches drooping in the dark, the sharputi and chital fish leaping, and then the rivers Karnaphuli, Dhaleshwari, Padma, Jalangi as well as the proverbial Dhansiri River itself, among others—distinctly and abundantly bespeak the poet's sensuous rootedness in rural Bengal.

In fact, this very Bengal comes to constitute a "concrete universal" in much of Jibanananda's work. It's not for nothing that the poet ardently announces in one of his sonnets, "Go wherever you desire—I'll remain by Bengal's banks."

But then, cities and their daily dirty dialectics—engendered by capitalism and colonialism—also figure profusely in much of Jibanananda's poetry. Even in his book Banalata Sen—as in his other works—city streets, trams, buses, gaslights, bricks, signs, windows, doors, roofs—among others—serve as pervasive, even governing tropes, while the bustle of slums and the busyness of bazaars, cries of street vendors and lepers on footpaths, day labourers and rickshawallahs, beggars and even the lumpenproletariat, etc, come to characterise much of the class-riven cityscape in Jibanananda, whose brand of modernism singularly represents the tensions and transactions between cities and villages, for instance. Indeed, Jibanananda was one of the most acutely class-conscious poets among the modernists in colonial Bengal.

And—as I have argued elsewhere—he even deftly mobilised the tropes of political economy within the spaces of his poems themselves, advancing his "micro-critique" of the commodity culture of capitalism and thus unsettling the otherwise misleading characterisation of this poet as a "purist," or as an "aesthete," indifferent to the dull prose of daily living. Indeed, the Jibanananda of political economy has remained unheeded in contemporary Bangla literary criticism.

Now, as for Jibanananda's broad thematic preoccupations in his poetry, one can go on and on naming them in a great variety of ways: for example, the contradictions between the temporal and the timeless within the determinate horizon of the historical, the metaphysics and the physicality of language and love, pre-history and even geological time, geographical-cartographical imagination, war and peace, social conflicts, deep nostalgia, the corruption and hypocrisies of middle-class politicians and businessmen, moral decadence in contemporary society, deadly pessimism yet tremendous optimism, and even the question of Revolution (it is not only interesting but also suggestive that he uses directly in his poetry the word "biplob" or "revolution" quite a number of times from, say, at least Mahaprithibee to Satti Tarar Timir to Bela Obela Kalbela, not to mention numerous poems discovered after his death).

In any event, one can easily see that the political and the philosophical profoundly intersect in Jibanananda's poetic spaces forged with boundless energeia and élan. I should also point out that the rhythms and pressures of his historical conjuncture—characterised by events such as World War II, communal riots and violence, famine, and the Partition of India, among others—have significantly informed his poetic sensibility and poetry.

Now, let me make a few more general observations about Jibanananda Das. True, he has most effectively and influentially shaped the idiom of modern Bangla poetry, while his persistent concerns with the entire range of places and peoples and seasons of his own land fiercely bespeak his anticolonial rootedness, underlining his brand of poetics that challenges Eurocentrism at every turn.

In fact, Jibanananda ultimately emerges as an anti-capitalist, anti-colonial, and anti-communal poet. And, thus, he is markedly different from some of his contemporaries known as the modernist poets of the 1930s—Sudhin Dutta (1901-1960), Amiya Chakravarty (1901-1986), and Buddhadeva Bose (1908-1974), for instance. Also, Jibanananda's relentless explorations of the historical and the unconscious—accompanied by his explorations of the various rhythms of time and of different spatial contours and constellations—have given his poetry the kind of textures as well as stylistic range and flexibility that were totally unknown before him. It is because of all this that Jibanananda is always with us.

Let me now conclude by commenting on his own statement about his poetry made in the preface to Shrestha Kabita (Best Poems). He himself told us that his work should not be reduced to pigeon-holing labels, many of which are already in circulation; rather, he looked for a critical consideration of his oeuvre in its totality. And the very question of totality continues to remain a challenge for the readers and critics of Jibanananda Das.

Dr Azfar Hussain is interim director of the graduate programme in social innovation, and associate professor of integrative, religious, and cultural studies at Grand Valley State University in Michigan, US. He is also the vice-president of the US-based Global Center for Advanced Studies (GCAS).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments