Folk songs of East Bengal

East Bengal has a population of about 45 millions and an area of about 15,000 square miles. Less than three per cent of its people have any education in the real sense of the term. The only way in which you can get to know this province, is to study its folk-songs and tales, which mirror its aspirations, achievements and frustrations.

An acquaintance with the geographical conditions of this province is necessary in order to understand and appreciate its folk literature. East Bengal is essentially a land of many waters, an intersecting network of streams and rivers. On these rivers and streams flows its trade and commerce; upon them depend its communications, and on the banks of these waterways are situated the main population centres of this province.

Bands of singers roam about from village to village singing poetical, religious or historical songs or more recent compositions about their own daily lives.

East Bengal's folk-songs are not unlike those of other countries. They are occasionally repetitive, even monotonous. Repetition and monotony, however objectionable from a literary point of view, are, it should be remembered, absolutely unavoidable in oral compositions. Their natural simplicity, however, provides a refreshing contrast to the sophistication of metaphor-ridden classical literature, and in their simplicity lies the secret of their appeal.

We shall offer below a few specimens of East Bengal songs but it is necessary to warn the reader that it is impossible to convey through translation any idea of their artless charm and their freedom from sophistication. It is difficult for an educated reader to appreciate properly the attitude of mind which these folk songs express; we are more often than not likely to forget that they enshrine the reactions, vague, unanalysed, of primitive minds to awe-inspiring natural phenomena; nor should we overlook the fact that the songs we are talking of, are actually sung in our villages, and unless you know the tunes, you miss the greater part of the beauty.

The village poet offers a faithful portrayal of all phases of life from childhood to old age. The newly born child is greeted with songs descriptive of the circumstances of his birth.

"Where is the child born?

The child is born in the house of Amir Ali.

In the lap of its mother the child asks for milk and rice

Where is the child born?

From the mother's lap the child goes to the father's

And asks for a melodious flute.

From the father's lap the child goes to the uncle's

And asks for beautiful dolls.

From the Uncle's lap the child goes to the aunt's

And asks for a ball of red thread.

Where is the child born?"

Other relations, the grandfather and grandmother, come in successively: the child's demands also increase. What we get is a charming insight into the pageant of family-life.

Segregation of the sexes in the rural areas of East Bengal had far-reaching influence on the folk-songs. Unmarried girls play an important part in certain social ceremonies. During periods of drought it is the girls who move from house to house in groups carrying with them a bronze vessel filled with water and painted yellow with turmeric and oil. The vessel is placed upon a winnowing fan along with a few grains of paddy, a few mango leaves, and some blades of grass. The privilege of carrying it falls to the most beautiful girls in the group. Each housewife, when the girls come to her house, sprinkles some drops of water over their bodies. The songs they sing on such occasions are reminiscent of ancient magic rites:

"In the house the plough neglected lies

In the burning sun the farmer dies

O rain come, never to go,

O rain come, never to stop

The paddy seed lies rotting

In the burning sun the farmer dies

O rain come in torrents,

The black clouds come

And black pigeons fly

The yellow clouds come

Any yellow pigeons fly

The red clouds come and red pigeons fly

O rain come, never to go."

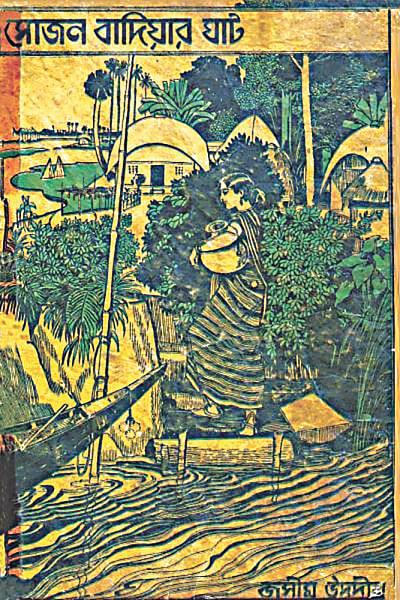

ROMANCE BY THE RIVER

Free mixing is frowned upon by society, but the inevitable attraction between the sexes overcomes the barriers of social convention and clandestine meetings between boys and girls are not infrequent. Such trysts usually take place in the neighbourhood of bathing ghats where the boys wait for the girls who come to fetch water.

Here is a beautiful dialogue between two lovers:

"Your pitchers, oh beautiful damsel,

Are starting ripples in the water.

Won't you smile and speak a few words to me

Now that nobody is with you?"

"I have no words to speak to a stranger.

Stand aside, let me fill my pitcher and go."

"Strange must be your parents

And stranger their hearts

That they have sent you alone to the bathing ghat with a pitcher".

"Good are my parents and better their hearts,

They have sent me alone to this bathing ghat with a stony heart.

But strange must be your parents

And stranger their hearts

That they have not arranged a marriage for so big a boy."

"Good are my parents and better their hearts,

They would have arranged a marriage

If for me they could get a beautiful bride like you".

"Shut up, oh shameless one,

You have no shame,

Drown yourself in the river

With a pitcher tied round your neck."

"Where shall I get the rope ?

I shall drown myself if you consent to be the water of the Jumna."

We shall now turn to peasants' songs. These are plaintive in tone and extremely nostalgic; they are sung usually when the cultivators work in jute or paddy fields. An unwritten law forbids the peasants to sing them at home. It is thought that women-folk find them irresistible. Many of them celebrate illicit love. The peasants sing them at night to the accompaniment of a flute as they keep watch over paddy fields.

In the specimen below the words are supposed to be those of a woman expectantly waiting for her sweetheart while the night passes:

'O night, you are almost ended!

The day is over, evening is come;

Candles are lighted in the home.

I cannot say how late

A women's love will knock at the gate!

O night, you are almost ended!

The first watch of the night is over,

The star-candles flicker.

I cannot say how late,

Cooking and preparing food, I wait.

O night, you are almost ended!

The second watch of the night has fled,

A shua bird cries in a tree o'erhead.

O night, you are almost ended!

The third watch of the night is fled;

The Ko'il shrilly calls o'erhead.

Open the door of the temple wide,

Let the cool breezes blow inside!*

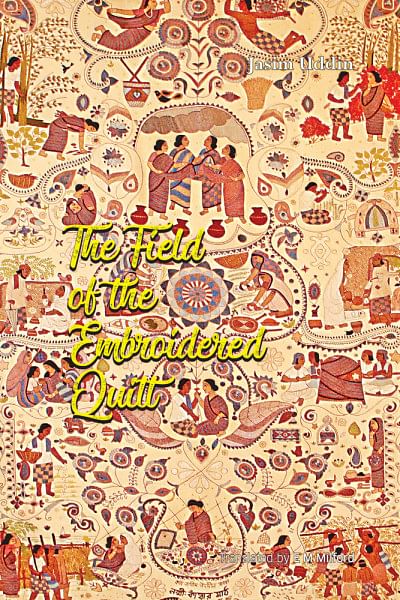

(Quoted from Mrs. Milford's translation of the author's "The Field of the Embroidered Quilt")

GHATU SONGS

We will next pass on to a category of songs current in the district of Mymensingh which form part of elaborate pageants and bear a family likeness to the dance songs out of which drama originated in ancient times. Each Ghatu Party includes, in addition to a chorus of singers, one or two dancers. These latter roles are usually played by the most handsome boys of the village who dress themselves for the occasion in women's attire. The songs of the chorus supplemented by the movements and gestures of the dancers unfold drama:

O my friend, whence comes the music of my love's flute?

For my love's sake I have left my home

And I tarry under the shade of a tree on a river-bank.

O my friend, whence comes the music of my love's flute?

There are various songs corresponding to the various ceremonies of marriage; together they form an integrated dramatic whole. The characters associated with different nuptial ceremonies have appropriate songs of their own. The utterances put into the mouth of each individual character sometimes form in themselves little pieces woven into the texture of the bigger drama. In songs celebrating the arrival of the bridegroom are introduced references to romantic stories of the past illustrative of similar situations. Hindu marriage songs generally use the symbolism of mythical tales; on the other hand, Muslim marriage songs are more realistic. The composers are invariably women; custom denies men-folk any access to the places where these songs are sung. One of their striking peculiarities is that the majority of these songs make no use of rhyme; they resemble metrical composition in classical languages like Sanskrit and the oldest specimens of Bengali poetry. They are specially fascinating for the scenes they depict of rural life down the ages:

"Nila fills a pair of caskets

With sandal paste and agur powder.

Nila goes to the river for water with a pitcher of gold."

"Cuckoo, you belong to the high tides

And you live among the low.

Anchor your boat a little further away,

Let me have a bath, O cuckoo".

"O Nila, you have grown so big,

But your hair-parting is unpainted.

Come with me Nila, your hair will be painted

O Nila, your hands lack bangles

Come with me, O Nila, I shall give you bangles to wear".

"If I go with you, O my cuckoo,

My uncle will be dishonoured,

If I go with you, O my cuckoo

My father will be dishonoured".

"I shall save your uncle's honour with money,

I shall save your father's honour with a respected bow".

The song that follows portrays a bathing ghat scene. A girl encounters a boy at the ghat and communicates her reaction to her attendants:

"Who is this nobleman bathing at my ghat

The water has turned entirely yellow like turmeric".

The man who has heard the remark comes to her house in the darkness of the night and sings:

"I know, Bibi, you are in love with me,

Open your door and let me in".

"How can I open the door?

My hair-parting is unpainted

I blush to sit by your side".

"Tomorrow morning, I shall send for the merchant

And buy you vermillion powder".

How shall I open my door?

My hands are without bangles"

"Tomorrow morning, I shall send for the merchant

And buy you bangles".

Marriages in our country are solemnised at the residence of the bride. Upon the conclusion of the nuptial ceremonies which include a feast, the bride is taken to her bridegroom's home. The occasion marks the beginning of a new phase in a girl's life; she is permanently separated from her parents and wrenched from her old moorings. Consequently, there runs through all songs relating to marriage a note of wistfulness, sorrow and tragedy. Separation from loved ones is a recurring theme, and has left a deep impression, not only upon our folk-songs, but also upon old Bengali literature.

The following song is a dialogue between bride and bridegroom on the eve of their departure from the home of the former's parents:

''The golden boat with winds for oars waits for us."

"Wait a little, O merchant's son!

Let me go and bid adieu to my mother"

"O Sua, dear, I have a mother at home

Who will be a mother to you also."

"Can the bark of one tree, O merchant's son

Be worn by another?

Can the bark of a sandal tree be put upon a mango tree?

The sweet words of my mother are sweet as honey

The words of your mother are as bitter as neem"

NARRATIVE SONGS

There are several types of these: simple stories, Ghazi songs. Tamasa songs, Lamba git and Jari. The character in these tales represent a bewildering assortment of figures drawn from such varied sources as the Bengali stories of Madhu Mala, Malancha Mala and Abdul Badsa and the Arabian Night's tales of Badiuzzaman, Jamal Kamal and Saiful Muluk; they consist of human beings, fairies and jinns who range unfettered through all times and places, the earth and the heaven, the past, the present and the future. Upon this vast and limitless stage are enacted the dramas that express the quintessence of the imaginative idealism of our people. These stories sometimes unfold tales of oppression and cruelty, of the trials and tribulations of the virtuous and of the ultimate triumph of truth; and sometimes tales of love and devotion, tales of the sufferings of women who in the midst of temptations and tortures keep the torch of their pure love steadily burning,

Lamba Git are current in the districts of Mymensingh, Tippera and Sylhet. Lamba Git literally means long narrative ballads. To the accompaniment of a sarinda and dotara, the leader of the party sings the story and the chorus repeats the refrain at intervals.

The Ghazi songs are conducted by professional singers. The leader carries a crescent-crested staff and an ornamental fan. The course of the narrative is punctuated at suitable stages by prose dialogues between the leader and the chorus. The narrative opens with an invocation:

"Hail to the Himalayas in the North

Whose winds shake the leaves of all trees.

Hail to the creamy ocean in the South

Upon whose waters sail the argosies of Merchants.

Hail to the lonely island in the far South beyond the oceans

Where Sadhu, the Merchant, cooked his meal and ate it.

Hail to the Sun King in the East

Who rises from one corner

And spreads his light in all directions.

Hail to Mecca and Medina in the West

To which the Muslim offers salams".

The invocation is followed by the proper story. These stories are mostly borrowed from the Arabian Nights deal with Muslim life. There are certain set descriptive patterns, handed down by word of mouth from generation to generation, into which they are fitted. Female beauty, a bride's toilet [sic], laments for the departed, merchant-boats, and so on, each of these topics has a set formula of its own.

FEMALE BEAUTY

"In her bridal dress she looks tall and slender

As though she has come down from heaven,

Her waist is so thin

That you can clasp it within the palm of a single hand,

Like a wind-shaken areca-nut-tree.

She sways from side to side.

She walks with the gait of a Khanjan bird.

And her eye-brows are like two bows drawn.

Her toilet completed,

She chews a pan

And puts to shame the sun and moon of the sky".

JARI SONG

The difference between Ghazi and Jari songs is two-fold. First the Jari ballads are based on Muslim religious stories whereas the material of the Ghazi ballads is borrowed from ordinary folk-tales. Secondly, they are sung in different ways. The main content of a Jari ballad is the martyrdom of Imam Hussain and the legends which tradition has woven round it. Into the main narrative are introduced, at frequent intervals, choral songs called 'Dhuyas' expressive of sentiments appropriate to particular situations. The Jaris also characterised by extempore musical debates between parties of singers. They are followed by dances, in the district of Mymensingh. The Jaris are essentially Muslim in character; the subjects and the atmosphere are Islamic, and to achieve this effect the singers use a large proportion of Arabic and Persian words.

There are unhistorical elements in the story of Imam Hussain's martyrdom as narrated in Jari ballads, but these unhistorical additions to the story are in themselves a unique record of the workings of the imagination of East Bengal, and a reflection of their spiritual adventures. We reproduce below two Dhuyas in which Sakina bewails the death of her husband in the battle of Karbala

Despair consumes my days, cries Sakina,

My husband promised to return

But he will come back no more.

Listen, o birds, I see you flying in pairs

But what have I done to deserve this fate?

Listen, mother dear,

You built great hopes on our marriage

But your load of merchandise has gone down into the water

Mother, says Sakina,

What consolation do you offer me?

Prepare some bitter poison pills for my death.

My husband was as stable as the sky

But that sky has now fallen to pieces

How should the heart of a dumb woman like me bear this sorrow

Were it a stone it would have cracked.

BAUL AND MARAFATI SONGS

The Baul and Marafati songs embody the philosophical speculations of our people and provide a record of the gradual evolution of religious thought in this country.

Close to my house lies the city of mirrors;

And in that city dwells a neighbour

But alas, I have never set eyes on him!

Endless waterways encircle the village;

There are no shores nor any boats.

Alas! how shall I cross?

How shall I describe my neighbour?

He has neither hands nor feet.

My neighbour and myself are thousands of miles apart,

Exclaims Shiraz the Fakir.

MURSHIDI SONGS

The Murshidis are devotional songs. "Murshid' means a religious preceptor, but the 'Murshidis' do not necessarily deal with the praises of the preceptor alone; they deal also wider religious topics. They differ from Bauls in their approach towards the problems of religion. The Baul's attitude to life is intellectual, whereas that of the Murshidis emotional. The Bauls aim at spiritual enlightenment through esoteric physical practices; the Murshidis aim at spiritual development through devotions:

O Allah be merciful,

I have none but thee to complain to.

I have none but thee to speak to.

My heart frets restlessly

Like the trembling waters of the ocean.

You make me drift from shore to shore

Like small hyacinth plants.

You make me weep

Like a madman who weeps by the roadway:

As the dumb dream, and keep their dreams to themselves,

So do I.

BOATMEN'S SONGS

East Bengal, we have already said, is a land of rivers. Our boatmen form no class by themselves, they are drawn from the ranks of landless cultivators who are obliged to seek their livelihood by working on boats for nearly six months in the year. During this period, they are completely cut off from their families, relatives and friends, and live on boats with the river underneath, and the sky over head. The sights they daily see, the dangers and perils of their existence, the stretch of the eternal sky and the uncontrollable fury of the water, induce in their minds a mood of mysticism and obstinate questionings". This is reflected in the words as well as the tunes of these songs known popularly as Bhatialis.

"The river has neither shore nor bank,

Who will now guide my movements from shore to shore?

Half the boat is sunk,

On whom will you now depend?

You will surely lose your life,

Unless Allah, the shoreless one, guides you to a shore.

Clouds are gathering across the river,

Flashes of golden lightning dazzle the eyes;

Shai shal flows the river.

Suddenly I see before me a golden picture,

But alas! I see it no more."

Thus the entire of East Pakistan finds expression in these songs written by anonymous tillers of the soil and toilers on the water, reflecting their loves and sorrows, their longings and fears and modest aspirations.

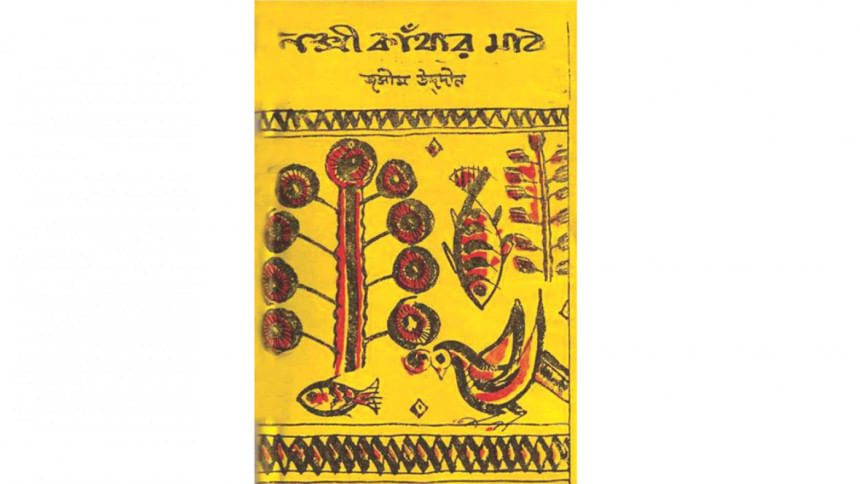

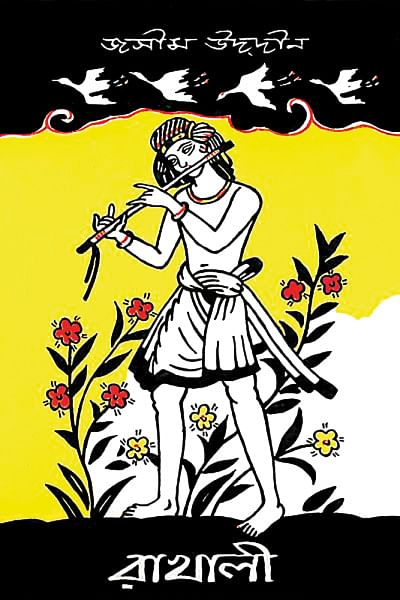

Jasim Uddin was one of the great literary figures of Bengali language and literature.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments