The villainy you teach me . . .

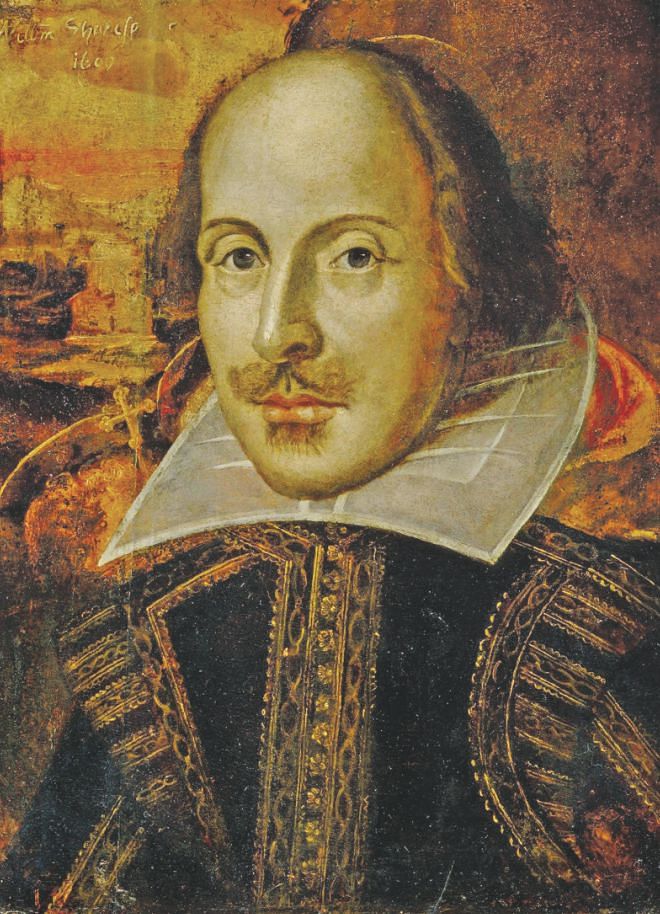

William Shakespeare would be four hundred and fifty years old, had he lived, on 23 April this year.

When you reflect on him, you tend to focus not just on literature but on an entire range of philosophy as well. He does not just come back to you every April. He is, has always been, with us. And just how he has managed to do that comes through the everyday acts in life you go through. You watch the stars in the night, beside some rural pond in Bangladesh or somewhere in a bush deep in Africa. And you recall Hamlet: “There are more things on heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy, Horatio.”

And there you have it, this acknowledgement of the huge mystery we call Creation. It is something that comes to us through the tranquil waters of faith. And Shakespeare evokes that call of faith, that sure sense of feeling involving the real and the imagined, or the shadow and the reality. You think of the ghost of Hamlet's father, of the truths that sometimes come revealed to men in their dreams or in their treks through deserted woodland paths. And you remember Shakespeare.

William Shakespeare is our man for all seasons. He brings to his thoughts the broad compactness of the universe and then transfers that compactness of experience to us. His comedies are perhaps the places where the common, huddled masses come resplendent in their pedestrian gleam. Nick Bottom. There is little question he is a buffoon, but then, aren't we all buffoons of some degree or the other in life? And the young fairyland woman who falls for his charms? Call that the effect of blind love. And love must be blind. What is that memorable line from the Bard again? Ah! “Love looks not with the eyes but with the mind / And therefore is wing'd Cupid painted blind.” So true, so true. If you wish to be in love, shut your eyes and imagine the feminine object of your desire in all her diversity of beauty. You will love the levels of adrenalin coursing through your being.

Macbeth loved his wife, even if it was, at a point, love induced by the lady's domineering tendencies. The proof? Well, he did go and try to kill Duncan, didn't he? And then there is Othello for you. He was a jealous man, a possessive husband. And he thought he was symbolic of masculinity. But make no mistake about it --- he loved Desdemona, for he could not imagine any other man passing on to her the priapic affections he so lavishly heaped on her. He did away with her life. The handkerchief is not important. Othello murders Desdemona. Browning, in later times, makes another envious lover kill Porphyria. Call it murderous love, call it whatever you will. It is there. You cannot run away from it.

Shakespeare's women, at least most of them, happen to be challengingly intelligent. No, not Amazonians, but women like Kate who throw down the gauntlet before proud men and then end up being in fierce love with them. But if Kate is fire and fury, Portia is cool, collected and inclined to the reasonable. She makes a gash on her patently alluring thigh to demonstrate her spousal feelings for the brooding, doomed Brutus. You have a sure sense that if Portia and not Calpurnia were married to Caesar, the Roman dictator would be persuaded to stay home and not walk to his death in the senate. Tragedy would not happen.

Often in Shakespeare, as also in the banality of life through the millennia, tragedy has been a straight offshoot of arrogance. Caesar believes he is constant as the north star. He is dismissive of the ides of March prediction, taunts the man who has served warning on him: “The ides of March are come.” The response is cool and deadly: “Ay, Caesar, but not gone.” In Caesar, you spot the human flaw which leaves scores of lives reduced to wrecks of dreams and ambitions. He understands the malignancy in Cassius: “Yon Cassius has a lean and hungry look. Such men are dangerous.” And yet he does not, will not smell the mischief already afoot. King Lear too will not see the brutish in his elder daughters' demeanour toward him. He pays a price, cradling the dead Cordelia in his arms and wondering why a rat, a horse, a dog will have life but his dear daughter none at all.

In Shakespeare and through him, you wonder all the way. Even as the blossoms dance before you, you wallow in the winter of your discontent. You do not take kindly to the grasping Shylock, but when he comes close to you, breathes down your face in all his centuries-old fury, you understand his loneliness. “Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands . . .” The pain in him is asphyxiating, for you, as you hear him condemn his tormentors: “If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die . . . The villainy you teach me I will execute. It will go hard but I shall better the instruction.”

It is Shylock's desperation and your resultant morbidity at play. Ah, the morbid! “Where's Polonius?” asks the king of the Prince of Denmark. “At supper,” answers the surly young man. “At supper?” wonders a worried monarch. And then comes the last word from Ophelia's lover: “Not where he eats, but where he is eaten.”

(William Shakespeare, born in 1564, died in 1616).

The writer is Executive Editor, The Daily Star

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments