The 'nowhere people' of the enclaves

THERE is a rather curious place inside Rangpur which goes by the name of Dahala Khagrabari #51. Upon close inspection the landscape provides no clues as to what exactly is it about the area that garners such curiosity and interest among locals and visitors alike. The land is a small 7000 m2 of farm land that belongs to a farmer who lives in the village called Upanchowki Bhajni, which encompasses the entire area of the land. The uniqueness of this land is that it is legally claimed by the district of Koch Bihar of West Bengal, in India. India claims this land as one of its many enclaves that exist inside Bangladesh. Dahala Khagrabari #51 also has the (mis)fortune of being the only third-order enclave in the world. That means that it is a piece of India within Bangladesh, within India within Bangladesh.

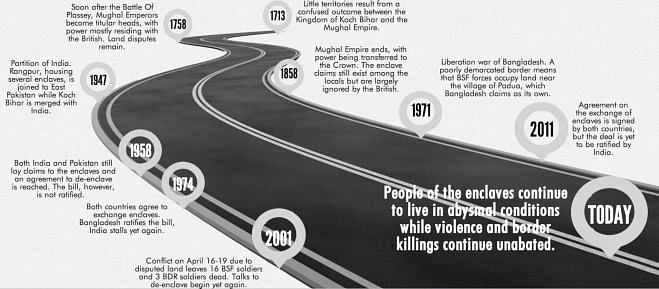

There might be a few raised eyebrows at the existence of such a claim on a small area of land, but it is nothing too surprising along the Indo-Bangladesh border. Near the border, there exist about 162 enclaves inside both India and Bangladesh (111 inside India and 52 in Bangladesh) that are claimed by the other country. The enclaves originated through a disputed and rather confusing deal between the Kingdom of Koch Bihar and the Mughal Empire in 1713. Famous legends say that these lands (or chitmahals, as they are called in Bangla) were used as bargaining chips to cover debts when the Raja of Koch Bihar played chess with the Maharaja of Rangpur. Tall tales aside, what seemed then as an irrelevant treaty over farm land, has now turned into prisons for almost 100,000 people living inside these enclaves.

The dispute over the enclaves stretched into colonial India, while the British ruled and the kings were denigrated to titular positions. However, they retained their claims and the locals continued in the same vein. The dispute became fiercer right after Partition, as India and Pakistan both laid claims on the enclaves on either sides of the border. A 'de-enclaving' agreement was reached in 1958, but the issue became a Supreme Court case in India and was never revived again. The War of Liberation in 1971 brought with it significant developments to this issue as the Indian forces aided Bangladeshi freedom fighters in their war against Pakistan. At this point, due to the poor demarcation lines, BSF forces took over a small strip of land near the village of Padua, close to the border. Bangladesh claimed it as its land while India refused to budge. The Indira-Mujib agreement on the border issue was signed in 1974, and while Bangladesh quickly ratified the bill and handed over Berubari to India, India was not able to hand over the Teen Bigha corridor to Bangladesh to connect Dahagram-Angarpota enclaves, due to lack of constitutional amendment and litigation by some aggrieved Indian nationals living along the border.

Talks were revived yet again in 2001 as conflict on the border reached tipping point as sixteen BSF troops and 3 BDR troops died in conflict. There was very little headway made until 2011, when India and Bangladesh signed an agreement to transfer enclaves to each other, giving the people of the enclaves the right to choose or repatriate to the country that claimed the enclave. The bill, though, is yet to be passed. It requires a constitutional amendment which was opposed by the Trinamool Congress and the BJP when Congress footed it. India's hue and cry stems from the fact that in this deal, India stands to lose a net worth of 40-square-kilometer of land.

The people of the enclaves live in an abysmal state of lawlessness. There is no electricity, no proper hospitals, no social institutions to provide them with anything. Residents of an enclave cannot cross the perimeter without infringing illegally into foreign. Since they do not have passports, they cannot ask for a visa from the host country. And to get a passport would mean crossing illegally, putting their lives at stake. The Teen Bigha corridor was leased to Bangladesh indefinitely to allow passage of the people of the enclave into the mainland but the situation is far from solved. In many areas, the small strips of enclaves have practically become prisons for its inhabitants, who grow up and die in that small perimeter.

The pertinent question is this: is it worth squabbling over a few odd acres of land while people's lives are at stake? The same people who have said, openly, that they care not a single jot about which side of the border they belong to; that they only wish to have a life where they are free to move without the fear of being shot by border security. The fact that this has carried on for as long as it has is a gross violation of human rights. At the same time, the residents of these enclaves are falling prey to fraudulent schemes by financial institutions that promise to store and pay interest on their money but end up stealing from them. The residents cannot complain to law enforcement authorities because crossing the border to complain will be seen as an even bigger crime.

The absurdity of the situation beggars belief and there seems to be no signs of this letting up. During her recent trip to Bangladesh, Sushma Swaraj said that the Modi-government is eager to come to a quick solution about this issue. How much of that is true remains to be seen. It was the BJP that opposed the passing of the bill by Congress, claiming that it was tantamount to sympathising with illegal Muslim immigrants from Bangladesh, in their bid to stoke the communal flames. In the end, the issue comes down to simple real estate for India, who have shown time and again their apathy towards the residents of the enclaves. Is the land worth wasting 100,000 people's lives? On current evidence, it would seem so.

The writer is Editorial Assistant, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments