Without judicial supremacy, all institutions will collapse

The Daily Star (TDS): What are the key reforms required for the judiciary in Bangladesh?

Jyotirmoy Barua (JB): Judicial reform revolves around judicial supremacy, with a key focus on entry-level appointments. The judiciary consists of lower and higher courts, yet the Constitutional Reform Commission (CRC) proposed abolishing subordinate courts without addressing necessary structural reforms. For example, Article 111 mandates Supreme Court rulings as binding on lower courts, but the CRC did not recommend amending this, creating contradictions.

Currently, subordinate court judges are recruited through a commission, often appointed after passing an exam with minimal training. This system allows individuals with limited practical experience to adjudicate complex legal matters. In the past, judicial appointments required maturity and experience, but today, candidates can memorise textbooks, pass exams, and become judges with little real-world exposure. A minimum of five years of legal practice before judicial appointment would ensure practical knowledge.

The appointment of Supreme Court judges in Bangladesh is governed by Articles 95 and 98 of the Constitution. Article 95 outlines judge appointments, while Article 98 addresses temporary appointments. The Supreme Court Judges Appointment Ordinance 2025 introduced changes, some necessary but others problematic. Despite stakeholder consultations, key concerns were overlooked.

Previously, the Chief Justice (CJ) appointed judges in consultation with the President, though political interference was common. The new ordinance shifts this authority to a Supreme Judicial Appointment Council, contradicting Article 95, which mandates that only the CJ nominates judges. Again, the CJ is designated as a council member, despite the council's stated purpose of advising him. If such a council were necessary, it should have been structured to allow the CJ to form it at his discretion.

Other members include senior judges from the Appellate and High Court Divisions, but the inclusion of a district judge is problematic. Article 152(1) defines an administrative unit as comprising judges below the district judge rank. Allowing subordinate judges to influence Supreme Court appointments disrupts judicial hierarchy and raises concerns about conflicts of interest.

Another issue is the Attorney General's participation in the council. As a political appointee, the Attorney General is susceptible to government influence, which could compromise judicial impartiality. Additionally, the ordinance allows the CJ to appoint a law professor or legal expert as a council member. However, professors lacking direct legal practice experience may not be suited to assess judicial candidates.

The ordinance's provisions appear to promote inclusivity by allowing lower judiciary members and external stakeholders a role in judicial appointments. However, this structure is unsuitable for the judiciary, where hierarchy is crucial.

Historically, around 70% of Supreme Court judges have been appointed from practising lawyers, while 30% have come from the judiciary. This balance recognises the distinct skill sets required in higher courts. Lower court judges primarily follow strict legal procedures, whereas Supreme Court judges must exercise judicial discretion. Judges accustomed to rigid procedural rulings may struggle with the broader interpretative role required in the Supreme Court.

Article 6 of the ordinance outlines the council's authority to nominate candidates and introduce additional eligibility criteria beyond those in Articles 95 and 98 of the Constitution. One such criterion is a minimum age of 45 years for appointment. Lowering this to 40 years would be more reasonable, as lawyers gain substantial expertise within ten years of practice. Talented legal professionals may be dissuaded from joining the judiciary if they must wait until 45, especially given the financial and professional constraints of judicial roles.

The ordinance also introduces qualifications related to candidates' education, professional experience, and publications. While these may appear beneficial, they introduce loopholes that disadvantage practising lawyers. Lawyers can begin practising with an undergraduate degree, whereas lower court judges often pursue postgraduate degrees at government expense. This discrepancy gives judicial officers an advantage in Supreme Court appointments, effectively reducing the number of lawyer appointees.

Judicial appointments should not be based on retrospective scrutiny of qualifications but rather on professional competence. Eligibility criteria should be established by the Constitution or Parliament, not left to an appointment council's discretion. By undermining merit-based selection, the ordinance fails in its stated objective of enhancing transparency and competence in judicial appointments. Instead, it exacerbates existing challenges, creating barriers to the inclusion of qualified legal professionals. To uphold fairness, merit, and judicial independence, these structural flaws must be addressed and rectified.

TDS: Given the limited time of the interim government, what specific measures can be taken to ensure long-term sustainability in addressing systemic issues within the judiciary?

JB: Not all systemic issues within the judiciary fall under the remit of the interim government; rather, internal management-related matters must be addressed by the judiciary itself. As the CJ holds the jurisdiction to oversee these matters, it is within his authority to determine the appropriate measures for resolving various challenges related to case management. This includes decisions on forming special benches to expedite the disposal of cases.

Within the Supreme Court, a separate General Administration (GA) Committee operates under the CJ. In line with long-standing tradition, the CJ consults with the GA Committee and senior judges when making decisions regarding judicial directives, case management procedures, and necessary reforms. These considerations extend to streamlining judicial processes and enhancing digitalisation—in some instances, full digitalisation is being explored—which are commendable initiatives. In my view, rather than burdening the interim government with these matters, the judiciary itself must be held accountable and pressured to address such issues independently.

Given the short timeframe of the interim government, its focus should be on laying the groundwork for an independent and transparent judicial appointment process—one that ensures judicial competence, maintains professional diversity, and upholds public confidence in the judiciary. If these foundational principles are not safeguarded, any short-term adjustments will fail to deliver sustainable improvements, ultimately shifting the burden of inefficiencies onto the general public.

TDS: How should judicial accountability, particularly in matters of disciplinary actions and the removal of judges, be addressed?

JB: The proposed reforms concerning disciplinary actions and the removal of judges initially included the establishment of an independent judicial commission for appointing Supreme Court judges. However, the recently enacted ordinance introduced a council instead. Notably, this ordinance was passed before the Constitutional Reform Commission (CRC) submitted its report and recommendations, thereby lacking a substantive basis. The CRC had recommended the formation of an independent Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC), composed of the Chief Justice as Chair, the next two most senior judges of the Appellate Division, the two most senior judges from the High Court, the Attorney General, and a citizen nominated by the upper house of the Constitution.

A new provision has also been introduced concerning investigations, granting the National Constitution Council (NCC), alongside the President, the authority to refer complaints to the Supreme Judicial Council. This adjustment significantly diminishes the President's exclusive authority, granting similar powers to the council.

Regarding accountability, in many countries, the Constitution is entrusted with ensuring judicial accountability. However, in countries like ours, where democracy remains fragile, relying solely on constitutional mechanisms poses significant challenges. Even before the 16th Amendment, when the Supreme Judicial Council was in operation, there was little evidence of judges being successfully scrutinised or removed. In many cases, they were forced into retirement rather than held accountable.

If a judge has a serious case of financial corruption against him, allowing them to leave in the name of protecting the judiciary's honour and dignity is not only detrimental but also undermines the very principles of justice. Thus, while the Supreme Judicial Council exists, its mere presence does not guarantee judicial accountability unless these systemic issues are addressed.

TDS: Can you elaborate on the proposed decentralisation of the High Court and its impact on the overall judicial process?

JB: During the Ershad administration, an initiative aimed to establish High Court benches in Chattogram and other locations to improve access to justice. While some litigants voluntarily approach the High Court, others are legally bound to do so when lower courts fail to provide adequate remedies. Decentralisation could reduce financial and logistical burdens for litigants outside Dhaka, similar to India's model, which has multiple High Courts across states and circuit benches in remote locations. Implementing a comparable system in Bangladesh could enhance judicial accessibility.

However, decentralisation presents challenges. Identical cases filed in different regions could lead to conflicting decisions, undermining judicial uniformity and increasing the burden on the High Court. The absence of a centralised case management system could further complicate legal proceedings. Given that writ petitions alone exceed 20,000 annually, decentralised benches would need to handle all case types, which could risk inefficiencies.

Practical experience suggests that decentralisation offers limited benefits. Resistance also exists among Dhaka-based judges and senior lawyers, who fear that decentralisation will disrupt established practice structures and diminish their authority. Decentralisation would redistribute cases, potentially making it difficult for experienced lawyers to maintain influence.

While decentralisation offers advantages in accessibility, its feasibility depends on structured implementation to ensure judicial consistency. Without addressing these concerns, the initiative remains uncertain in its effectiveness.

TDS: What measures should be taken to reduce the backlog of cases, and how should the root causes of delays in the judicial system be addressed?

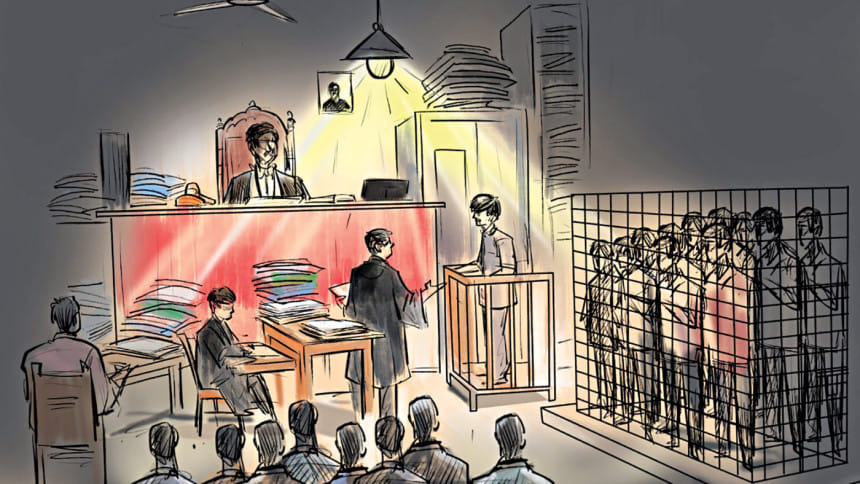

JB: The judiciary's backlog exists at both lower and higher courts, but the High Court faces a particularly severe and growing crisis. This surge in cases does not indicate increased legal awareness or trust in the system but rather reflects rising social injustice. Litigation has increased due to systemic injustices and administrative failures. With the state itself involved in criminal activities for over 15 years, it is inevitable that the judiciary will experience an influx of cases.

Judicial inefficiencies and case backlogs stem from structural flaws, further complicated by political appointments. Many judicial recruits, appointed through political affiliations, prioritise monetary incentives over legal integrity. Due to inadequate remuneration, they often lack the motivation to prepare for trials. Ensuring adequate compensation and establishing independent oversight could help ensure accountability.

Expanding access to legal aid could also help, but awareness and accessibility remain challenging. Major reforms are required in case management. Dr Yunus once compared the system to a "cage" where accused individuals face dehumanising treatment before trial. Justice demands that all be presumed innocent until proven guilty. Thus, reform is essential, particularly in judicial management, legal education, and recruitment, to address systemic failures and reduce case backlogs effectively.

The interview was taken by Miftahul Jannat.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments