Jatra

What a tremendous roar of thunder!

What a dooms day!

Why does the thunderbolt not strike my head?

Oh time, devour me,

Oh thunder, destroy this degenerate soul,

Oh goddess of darkness-

Why keep this villain alive in this world,

Destroy him!

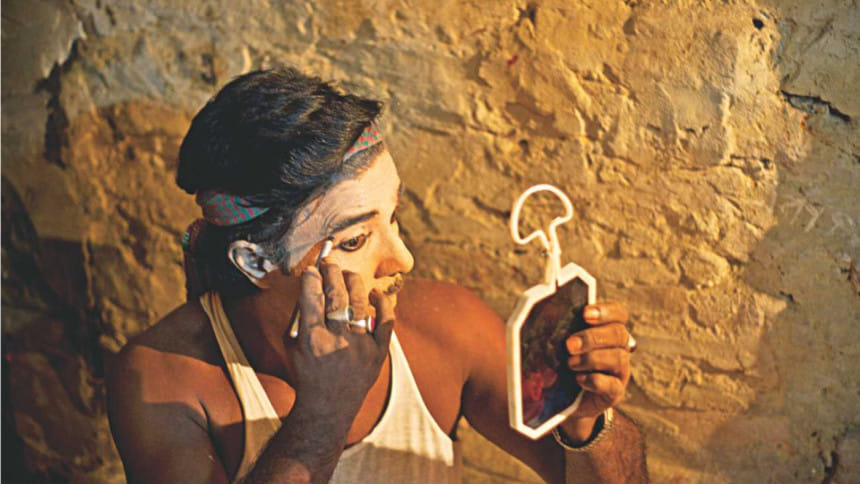

Thus thunders the hero, his voice reaching far and wide, capturing the full attention of his audience. The language of jatra, a community drama entrenched in the very roots of Bangladesh, is so poetic, rhythmic, enchanting and dramatic that it exudes a power that is captivating, alluring even.

In its earliest form, jatra was a performance based on spirituality; later it brought in social and historical elements. Popular amongst the rural communities, jatra was an instrumental cultural form to fight the oppressions of the British regime. Back then it was used to promote the swadeshi movement, as can be witnessed from the jatra pala Matri Puja (1906), written by Mukunda Das, which was charged with anti-state sentiments. Das was eventually charged with sedition, imprisoned and fine Rs. 300, a huge sum back then. And yet he would sing:

"O ladies of Bengal,

Do not use the mercerised bangle-

Throw it on the ground,

Wake up, wake up, hey ladies!"

In 1971, jatra was used to mobilise people. Many Bangladeshi refugees would collaborate with organisations in Kolkata during the Liberation War to put up jatras. Performances such as I am not Mujib, written by Monmotho Roy, Sangrami Mujib by Naresh Chakraborty and Bangabandhu Mujibor by Satya Prakash Dutta mostly inspired the Bangladeshis in Kolkata, uplifting their morale and keeping alive the spirit of liberation.

The long historical development of jatra is the pride of Bangladeshis. In rural areas, many aspiring actors take up this art form as their career. However, despite its historical relevance, jatra performers are facing an uncertain future.

Jatra owners are mostly wealthy influential men of the locality, who run a jatra troupe to earn as much profit as they can. It is alleged that many of the current jatra proprietors used black money to buy the troupes and have no taste or aesthetic sense. Today, jatra has gained notoriety, mostly for its crude language and obscene dance performances. It is thus natural that this art form is losing its popularity.

There are approximately 7,000 professional jatra artistes in Bangladesh. Even today, the genuine artistes want to leave behind the legacy of jatra as an art form that can eventually become a credible industry for rural artistes. But that is becoming more and more difficult. Jatra performers do not even get paid properly. Most of the time, they are not even paid according to their agreements. According to Tapan Bagchi in Bangladesher Jatra Shilpider Jiban o Jibika, 10.9 percent jatra artistes and workers receive less than Tk. 1000, 47.8 percent artistes earn around Tk. 2000 or less, 18.5 percent artistes take home Tk. 3000 or less, and 15.2 percent artistes earn Tk. 4,000 or less. They thus either have to depend on their family for financial assistance or work in over 100 troupes over the year to make ends meet. There is also discrimination according to "grade", with higher grade actors afforded special treatment, and better pay and facilities.

If jatra artistes continue to work under private ownership, they will never be able to make full use of their potential. That's why a cooperative needs to be established so that jatra performers can actually earn a substantial amount for their work. It is imperative that the artistes themselves form a guild that can ensure their subsistence. Perhaps it is also time for more research to be done on this art, as these studies can be used to transform the current jatra form to a tool for social mobilisation and change.

Qualitative change is also necessary, and accordingly, contemporary themes should be introduced when writing jatra palas to keep pace with the current times. Reportedly, it takes Tk. 20,000 to 30,000 to get permission to stage jatra performances. There is obvious corruption within law enforcement agencies, and as unscrupulous jatra owners seek to use obscenity to titillate their audience, they further promote corruption by giving in to the demands of the law enforcers.

According to Article 23 of our Constitution, "The state shall adopt measures to conserve cultural traditions and heritage of the people and to foster and improve the national language, literature and the arts that all sections of the people are afforded the opportunity to contribute towards act to participate in the enrichment of the national culture." Preservation of jatra in its original form is thus not just a moral duty but an obligation for the state. And yet, when compared to other art forms, there is widespread discrimination, gender and wage disparity, lack of funding and gross neglect from the authorities. There are no training opportunities for jatra artistes and thus, there is no scope for further development of their art.

Like with many other art forms, religious fundamentalists are the major enemies of jatra. If we can recall, seven years ago, a group of extremists bombed a jatra pandal, raising vehement, vulgar slogans against this art form. Being an open air performance accessible to all, jatra is especially vulnerable to fundamentalism and extremism. Yet, the government has not taken any concrete steps to protect jatra artistes and their means of livelihood.

Rural jatra artistes have dedicated themselves to jatra performances so passionately that they cannot think of accepting any alternative livelihood. And yet most of these artistes are so poor that they have no proper housing, food or health care facility, while their children cannot even attend school.

We cannot let this ancient art form crumble under these pressures that can be easily contained if the concerned authorities so wish. It is important for jatra to go back to its original people-oriented form if it were to sustain. But we, the nation, need to provide systematic support to return this art form to its original glory.

Nazmul Ahsan, Ph. D is a freelance researcher and a cultural consultant based in Khulna.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments