The making of Bangladesh’s leftist politics

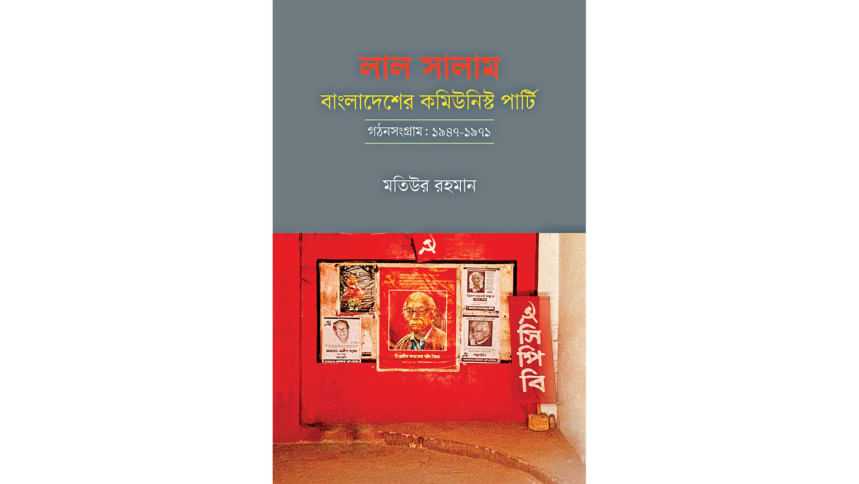

The history of Bangladesh's leftist politics is a story of unity and division, of shared ideals splintering into competing paths. Despite drawing strength from the same ideological roots, the movement has long been defined by factionalism, shifting strategies, and contested visions for the future. For anyone seeking to understand Bangladesh's political journey—from the Partition of India in 1947 to the Liberation War of 1971—these struggles within the left provide essential context. Matiur Rahman's recent work, Laal Salam: Bangladesh's Communist Party, shines a light on this complex landscape, offering a rare window into the forces that shaped, divided, and defined the country's leftist politics.

The ideological roots of the left trace back to Enlightenment and revolutionary thinkers—Voltaire, Paine, Bentham, and above all Karl Marx—whose writings gave shape to the intellectual foundation of socialist and communist politics. Their ideas travelled across continents, igniting movements that challenged power and reimagined society. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 marked the moment when theory translated into power, as a communist party for the first time seized control of a state. South Asia soon felt the reverberations.

Marxism's dawn in Bengali intellect

The emergence of Marxism in Bengal was a dynamic interplay of intellectual discovery, political disillusionment, and the pressing socio-economic conditions of the time, gradually transforming into a significant intellectual and political force. It was not a sudden transplantation but rather a gradual evolution, influenced by a confluence of factors.

By the 1920s, a growing number of Bengal's revolutionaries began searching for an ideology that went beyond the limits of nationalist slogans and sporadic acts of violence. Confronted with the stark realities of colonial exploitation and entrenched social inequality, many found in Marxism a framework that spoke directly to the need for structural change. In prisons and detention camps, they came across Marxist texts that reshaped their political imagination. The triumph of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, and the bold Soviet experiment that followed, further deepened this turn, fuelling a socialist consciousness that would soon take root across Bengal's political landscape.

The efforts of Indian revolutionaries living abroad, who made early contacts with groups like Anushilan and Jugantar in Bengal, played a crucial role in introducing Marxist concepts. The 1920s saw significant efforts by Indian expatriate revolutionaries such as M. N. Roy, Virendranath Chattopadhyay, Ghulam Ambia Khan Luhani, Bhupendranath Dutt, Abani Mukherjee, and Panduraj Khankhoje. Operating from abroad, they established crucial contacts with Soviet leaders in Moscow, including Vladimir Lenin, and played a key role in integrating Marxist ideologies into the Indian political landscape. For a detailed account of these expatriate revolutionaries, see Ghulam Ambia Khan Luhani: Ek Ojana Biplobir Kahini by Matiur Rahman, editor and publisher of the Daily Prothom Alo.

The translation of Marxist classics into Bengali, though initially slow, gradually made these ideas accessible to a wider intellectual audience. Early communist figures such as Rebati Barman were instrumental in translating and disseminating Marxist texts. Moreover, the Bengali journals of the time became crucial arenas for vigorous debates on Marxist theory, reflecting both the multiple shades of Bengal Marxism and its critics.

A key aspect of Marxism's theoretical emergence in Bengal was its strong engagement with the cultural and intellectual arena. From the mid-1930s onwards, arts and aesthetics became important for Marxists. Intellectuals debated how Marxism could be integrated into Bengali literature, art, music, and theatre to propagate socialist ideals. The "Progressive Writers' and Artists' Association" and the "Indian People's Theatre Association" were founded to spread socialist ideas through cultural mediums. Poets like Kazi Nazrul Islam were deeply impressed by communist ideals, writing about social justice and editing journals focused on workers and peasants.

While the Communist Party of India was formally founded in 1925, various communist groups were active in Bengal in the 1920s and early 1930s. These early groups, though often operating under colonial bans, laid the organisational and theoretical groundwork for the wider adoption of Marxism.

Politics in a divided land

In the aftermath of Partition in 1947, the Communist Party of Pakistan emerged as the country's first leftist political organisation. At the Communist Party of India's second congress in Calcutta in 1948, the party was formally split into two, giving rise to a separate Pakistani branch. A nine-member central committee was elected to lead it, and March 6, 1948 was officially recognised as the founding date of both the Communist Party of Pakistan and its East Bengal wing.

Initially, the Communist Party agreed to cooperate with the East Bengal government; however, this accord did not last long. Between 1948 and 1950, several peasant movements and uprisings took place under the leadership of the Communist Party of East Bengal. The Party was influenced by the ultra-revolutionary line of B. T. Ranadive, the then general secretary of the Communist Party of India. Many party activists were killed and imprisoned during these events. As party members went underground, they became largely disconnected from the general populace. Following widespread criticism of the ultra-revolutionary line, a 1951 conference in Calcutta resolved that the Communist Party of East Bengal (later the Communist Party of East Pakistan) would operate by working within other political parties.

Over time, the Communist Party of East Pakistan underwent further divisions. The 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party in 1956 marked the beginning of a schism within the international communist movement. From the early 1960s, this division spread to the Communist Party of India, which split along Soviet–China lines, and it also influenced the fragmentation of the Communist Party of East Pakistan. After Bangladesh's Liberation War, these rifts deepened, giving rise to multiple ideological streams within the country's communist movement. Amid these divisions, the Communist Party of Bangladesh is considered a leading branch.

A considerable body of research-based literature has been produced on the history of the Communist Party of Bangladesh. Alongside these works, autobiographies and memoirs by leading figures associated with the party provide more personal perspectives on its political journey. Adding to this body of knowledge, the recently published Laal Salam: Bangladesh's Communist Party stands out as a distinctive and timely contribution.

A considerable body of research-based literature has been produced on the history of the Communist Party of Bangladesh. Alongside these works, autobiographies and memoirs by leading figures associated with the party provide more personal perspectives on its political journey. Adding to this body of knowledge, the recently published Laal Salam: Bangladesh's Communist Party stands out as a distinctive and timely contribution.

Matiur Rahman, the author, maintained a close association with the Communist Party for over three decades, beginning in the early 1960s. During this time, he played an active role in many of the party's activities and publications, eventually rising to leadership positions, including membership of the central secretariat and serving as international secretary. He also edited the party's official mouthpiece, the weekly Ekota, for an extended period, and was involved with other significant publications such as the underground Shikha, the bi-monthly Muktir Diganta, the literary journal Gonosahitya, and during the Liberation War, Muktijuddho. This long engagement gave him unparalleled access to party documents and archives, much of which he helped to preserve.

Rahman notes that the publication of this book, the product of years of effort, was also a way to acknowledge his debt of gratitude to the party and its leaders. He dedicated it to two of the most prominent figures in Bangladesh's communist movement—Comrade Moni Singh and Comrade Mohammad Farhad.

The book brings to light several little-known dimensions of familiar political events. One such episode is the landmark Jukto Front (United Front) election of 1954. While this election has been discussed extensively in historical and political literature, the role of communist candidates remains only partially understood. Some communists contested under the banner of the Communist Party, others as independents, and still others as Jukto Front nominees. Despite the repressive measures of the Pakistani authorities, a number of them managed to secure victory. Yet, the exact tally of successful communist candidates has long been a matter of debate, with different sources citing conflicting figures.

Drawing on the 1977 report of the Bangladesh Election Commission as well as contemporary newspaper accounts, this book attempts to clarify the record, confirming that 24 communist and leftist candidates were elected. It also makes an important distinction: the noted leftist leader Sardar Fazlul Karim entered the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan in 1955, but his election was separate from the 1954 polls and should not be conflated with them.

The book also offers valuable insights into the wide-ranging contributions of communists to the political, cultural, and social landscape of early East Pakistan. Among the initiatives discussed is the formation of the Jubo League in 1951—distinct from the present-day organisation—which stood as the first progressive youth platform in East Pakistan. The narrative also traces communist involvement in the Language Movement, the creation of the East Pakistan Student Union, their active role in literary and cultural circles, and the establishment of the Peace Council.

Another key development in Pakistan-era politics was the formation of the Ganatantri Dal (Democratic Party). Faced with the Pakistani government's repressive policies, communists found it increasingly difficult to operate openly under their own banner. To continue their activities, they advanced their politics through this new platform. The book explores the motivations behind the Ganatantri Dal, its organisational evolution, and its eventual decline.

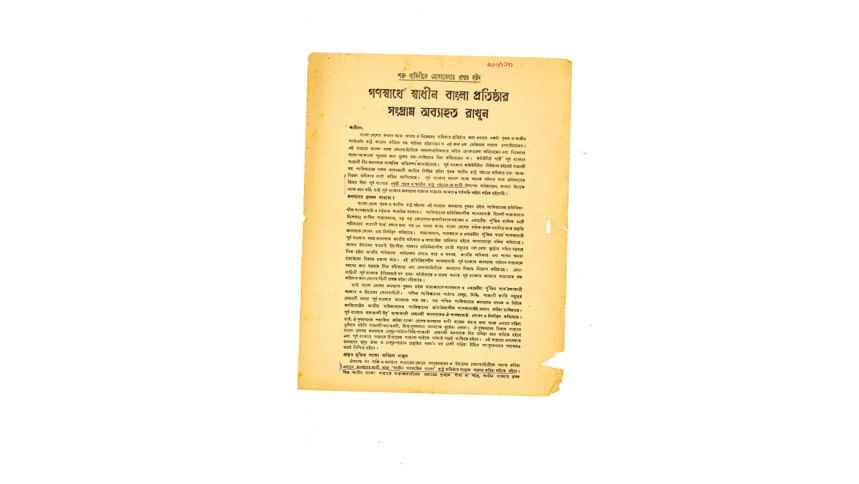

The communists played a central role in the formation of the Jukto Front during the 1954 elections. Yet the victory was short-lived: arrests and detentions of communist leaders began almost immediately afterwards, and by July 1954 the party was formally banned. Here, the book underscores the decisive role of both the Pakistani state and the United States administration in suppressing communist activities, bringing to the surface aspects of these events that have received little attention in earlier accounts.

Struggle for democracy

With the imposition of martial law by Ayub Khan in 1958, Pakistan entered an era of autocratic rule. Yet, communists in East Bengal remained deeply engaged in the democratic struggle, sustaining their involvement in movements and protests throughout the following decade. Drawing from Matiur Rahman's extensive personal archive, Laal Salam reconstructs this history by presenting rare documents, including the political report, programme, and proposals adopted at the Communist Party's first congress in 1968. These papers reveal a striking fact: the idea of an independent Bengal was being formally considered within the Party as early as that year.

Rahman's account is not simply archival but deeply personal. As an active participant in the student movement against martial law—launched on 1 February 1962—he occupied a unique position, simultaneously maintaining clandestine links with the Communist Party leadership while publicly working with the East Pakistan Student Union and the broader student movement. His testimony situates East Bengal's activism within a global moment. The 1960s were a high point for student movements across the world—from Africa and the Americas to Asia and Europe—driven by opposition to war and imperialism, demands for civil rights and democracy, the rise of countercultural politics, and Cold War anxieties. Most of these currents resonated powerfully in East Pakistan, fuelling Bengali students' anger at the authoritarian regime and strengthening their yearning for democracy and independence.

Following the Communist Party's first congress in 1968, the nation's political milieu underwent rapid transformation. The Student Union and the Student League, reaching a significant accord, resolved to augment Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's seminal Six-Point Programme into an Eleven-Point Programme. This new manifesto incorporated the demands of workers and peasants, called for the nationalisation of banks, insurance companies, and major industries, and advocated an independent, anti-imperialist foreign policy. On January 4, 1969, the Eleven-Point Programme was formally announced, sparking a mass movement across East Bengal that culminated in the historic uprising of 1969 and the eventual downfall of Ayub Khan's regime.

The years that followed, from 1969 to 1971, were marked by profound upheaval, ultimately leading to the birth of Bangladesh. During the Liberation War, the National Awami Party, the Communist Party, and the Student Union came together to form a united guerrilla front against Pakistan's military regime and its local collaborators, including the Razakars, Al-Badr, and Al-Shams. The Party also played a crucial role in mobilising international opinion in support of Bangladesh's independence. Rahman's collection preserves rare leaflets, circulars, evaluation reports, and booklets that document this struggle, while his own first-hand participation in both the 1969 uprising and the Liberation War lends authenticity and immediacy to the narrative.

The book is further enriched by historically significant appendices, including the Communist Party's 1948 leaflet on armed revolution, the US State Department's 1950 programme against communism in East Bengal, the Party's 1953 draft political programme, short profiles of communist candidates in the 1954 Jukto Front elections, lists of political prisoners released in 1955–56, and the text of Anil Mukherjee's speech representing East Pakistan at the 1969 Moscow conference of 75 communist parties.

In tracing this history, Laal Salam makes clear that the Communist Party of Bangladesh's early years were defined by formidable challenges and relentless repression. Its formative journey was far more complex than most existing accounts acknowledge. From the creation of Pakistan in 1947 to the emergence of Bangladesh in 1971, the Party remained deeply woven into the nation's political, social, economic, and cultural struggles. Any serious account of Bangladesh's political history would be incomplete without recognising this role. By drawing on both documents and lived experience, Rahman offers not only a historical record but also a portrait of resilience, defiance, and the uncompromising determination of the Bengali Left in the face of systematic suppression.

Khalilullah is the Climate Project Manager at The Daily Prothom Alo.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments