The crime of being Bengali: The untold story of Bengali internment in Pakistan

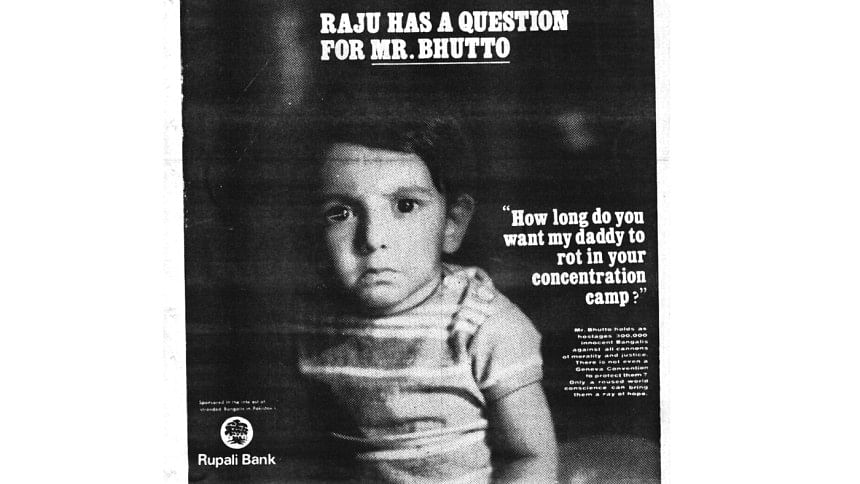

In the immediate aftermath of the Bangladesh Liberation War, as world attention fixated on the harrowing human toll of conflict and the fate of 93,000 Pakistani POWs in Indian custody, a darker, largely buried chapter was quietly unfolding in Pakistan. Thousands of Bengalis—military officers, civil servants, and civilians—were interned in Pakistan. Once loyal to the Pakistani state, these men and their families were recast overnight as ghaddar (traitors) and interned in about fifty camps across the country, pawns in a political standoff between Islamabad, Dhaka, and New Delhi, flung into a bureaucratic abyss of internment, and erasure.

Their crime? Being Bengali in a state that had disavowed their existence. An estimated 81,000 Bengalis were detained. These were soldiers held — not as combatants, but as hostages. They were civil servants, army officers, and government employees stationed in West Pakistan, part of the same state machinery they had earnestly served. Their lives were used as a grotesque currency in trilateral negotiations between Islamabad, New Delhi, and the nascent government in Dhaka. Pakistan used them as leverage to negotiate the return of its soldiers from Indian captivity. This was also tied to precluding the POWs from being tried for war crimes and to recognising Bangladesh as a sovereign state. What followed was not merely state retribution, but the calculated dehumanisation of a people rendered stateless and expendable.

Citizens Turned Traitors

Denationalized, de-personed, and dispossessed, these individuals were transformed from citizens into an internal other through the labelling of ghaddar, whose bodies had to be marked out both legally and socially as that of a traitor, after which they could be interned without any consequences. Their incarceration was not an aberration but in fact a deliberate state strategy: a moral betrayal disguised as political pragmatism.

Just days after the war ended, a petition by Punjabi bureaucrats demanded the expulsion and incarceration of Bengalis in West Pakistan. The state acted swiftly. Passports were seized, bank accounts frozen, and people rounded up and transported to remote internment camps. Held in makeshift prisons—ranging from British colonial forts to abandoned schools and military barracks—these Bengali internees were subjected to harsh and often inhumane conditions. By early 1973, more than fifty camps had been established, some of which were termed 'collection camp', 'transit camp', 'general repatriation centre', 'married camp' or 'bachelor camp', and some of which were transitory in nature.

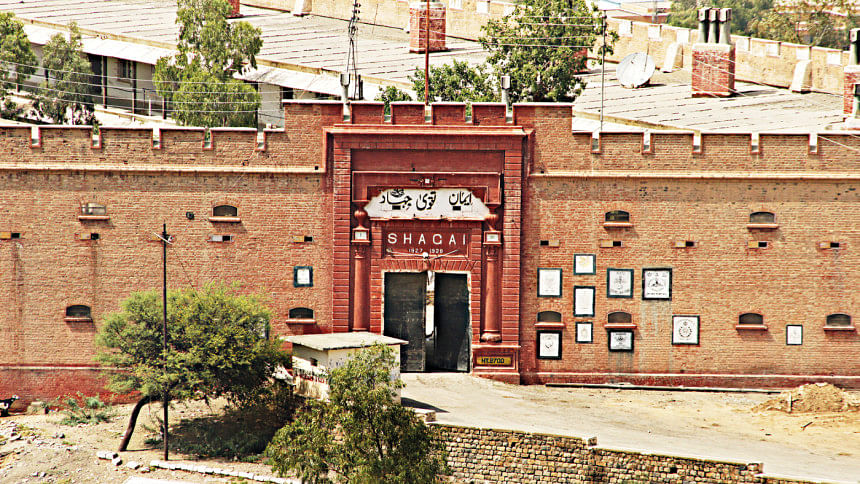

Shagai Fort: A Forgotten Hellhole of Internment

Nestled near the Afghan border, Shagai Fort—once a British outpost guarding the Khyber Pass—became one of Pakistan's most notorious internment sites following the 1971 war. From 1971 to 1973, thousands of Bengali detainees were confined here under horrific conditions that many described as 'subhuman'. Twenty men crammed into a single room. No beds, no sanitation, no medical care. Disease swept through the overcrowded facility, with outbreaks of influenza, fever, and chickenpox taking a deadly toll. 'They were living in subhuman conditions', recalled one escaped Bengali soldier. 'There were no latrines, no medical aid—and for months, no beds'.

The fort, originally designed to house a much smaller contingent, quickly became overwhelmed as more detainees arrived. Despite attempts to expand the infrastructure, it remained drastically insufficient for the swelling numbers. A report by the International Committee of the Red Cross confirmed the dire situation: 'the diet was inadequate, medical facilities were non-existent, and hygiene conditions were appalling'.

These conditions inevitably led to several desperate attempts to escape from the camp and reach the neighbouring Afghan borderland, with few successes. The daring escape by five Bengali officers—Captain Nazimuddin, Lieutenant Mohammed Alim, Lieutenant Syed Ali Mahmood, Flying Officer Rafiqul Haq, and Cadet Mohiuddin Khondkar—briefly thrust the camp into the spotlight. They fled on foot across treacherous terrain toward the Afghan border. BBC New Delhi aired interviews of some escapees from Shagai Fort: 'They were held there for almost a year and were not allowed to go out or to have visitors. They were denied all basic facilities necessary even for criminals lodged in jails'.

But not all were so lucky. Many who attempted escape were caught and subjected to solitary confinement, with some driven to mental breakdowns. As escapes increased, 'local armed tribal militia' were deployed to guard the fort, with the authority to 'shoot anyone trying to escape. They did shoot one officer when he jumped outside from the rooftop'. Despite the hardships they faced, the internees demonstrated remarkable resilience through various means – drawing strength from religious observance, participating in sports and cultural activities.

Today, the grim legacy of Shagai Fort remains largely unacknowledged—a silent witness to the suffering of those forgotten by both history and politics.

Sandeman Fort: Where Captivity Meant Dehumanisation

Located about 280 miles northeast of the city of Quetta, Fort Sandeman in Baluchistan, once a colonial outpost, became one of the largest internment sites for Bengalis detained in Pakistan after the 1971 war. At its peak, the camp held nearly 10,000 people—including soldiers, doctors, engineers, and their families. The conditions were grim. In cramped 20-by-20-foot barracks, entire families were forced to live behind makeshift partitions made from torn sarees and blankets. 'A dismal sight reminiscent of a refugee camp', one Bengali officer wrote in a letter smuggled out of the facility in April 1972.

Class and rank shaped daily life behind the barbed wire. Officers and their families received better medical care, while enlisted soldiers—referred to as 'other ranks'—suffered from a lack of even basic medicines. The fort was divided into five segregated 'wings' based on rank, family status, and arbitrary moral judgments. Some rules bordered on the absurd. Adult men without family accompaniment—whether bachelors or married soldiers—were prohibited from living near their loved ones. Colonel Chowdhury's young son, placed in a 'bachelor wing', was forbidden even to speak with his mother. The restrictions, internees argued, were less about discipline and more about humiliation.

Escape attempts were rare but serious. Those caught were subjected to harsh punishment. 'Deaths were few', a survivor recalled, 'but every escape attempt caused widespread panic'. Despite the hardships, the internees made efforts to preserve some sense of normalcy—especially for their children. Over 100 children were housed in the camp, and internees formed a school. Women took up teaching roles, showcasing resilience in the face of uncertainty and confinement.

A diplomatic breakthrough came in late August 1973 when India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh signed a tripartite agreement. Under its terms, Pakistan consented to repatriate all interned Bengalis—including those in prisons and psychiatric institutions—in exchange for the release of its POWs held in Indian custody. By mid-1974, nearly 120,000 were returned to Bangladesh. But the ordeal didn't end there.

'bastard repatriate(s)': Stigma After Return

When the detained Bengalis in Pakistan were finally repatriated to Bangladesh in 1974, their return was met not with relief or celebration, but with suspicion, scorn, and silence. Branded as collaborators and dismissed from service, many were denied promotions and labelled 'bastard repatriates'—a cruel phrase that captured the bitterness of postwar politics. Among them was Shafiul Azam, East Pakistan's former chief secretary, who was blacklisted by the new Bangladeshi leadership. His crime: appearing in a Pakistani-produced documentary, Ghaddar. Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, influenced by political insiders, reportedly could not 'even tolerate the mention of Mr. Azam's name'.

Another victim of this silent purge was Tabarak Hussain, a senior foreign service officer held at Shagai camp. Though he had stayed behind to protect his wife and children, his peers saw it as weakness. Upon his return, he was demoted. A British diplomat observed that Hussain—once considered an 'honourable public servant'—had been reduced to a 'political pawn'.

The tensions between repatriates and the veterans of the liberation war were not just about bureaucratic ranks or political position. They ran deeper—cutting through the very identity of the newly liberated nation. While 'freedom fighters' were celebrated as patriots, repatriates were portrayed as tainted, sometimes traitorous, carrying a Pakistani 'mentality' incompatible with the spirit of Bangladesh's liberation. Yet, after Mujib's assassination in 1975, many repatriated officers found new footing under the regimes of Generals Ziaur Rahman and H.M. Ershad. Tabarak Hussain, for instance, unexpectedly rose to become Bangladesh's Foreign Secretary from 1975 to 1978. Certainly, the internment in Pakistan had provided a framework for a community of servicing classes to establish bureaucratic links and kinship ties. The post-internment experience too belongs to the 'hidden history(s)' of 1971, obfuscated by reductive nationalist histories and one-dimensional war memoirs and sacrifices.

Still, the political, psychological and social scars of internment remained. Many repatri-ates avoided discussing their pasts, fearful of surveillance or political reprisals. Some went as far as to erase traces of their captivity from personal histories. For their chil-dren, growing up with a 'repatriated father' often meant enduring whispers, doubts, and an inherited stigma. Their stories remain largely absent from official accounts and pop-ular narratives of 1971. These men and women are not celebrated in nationalist histories. They occupy what Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot famously called 'silences within silences'—those stories deemed too inconvenient for national myths.

Half a century has passed since Bangladesh's birth, but the moral reckoning for what happened to these people is far from complete. Will their suffering ever be formally acknowledged? Will they ever discover the sites of power where internment methods were designed to justify their encampment? Will reparations or apologies be offered? Will their children learn that their parents were not cowards, but casualties of diplomacy and betrayal? Lastly, will the story of their internment ever be common knowledge in Pakistan and Bangladesh?

Until these questions are answered, the internment of Bengalis will remain a moral wound—unhealed, unspoken, and unseen by those who choose not to look.

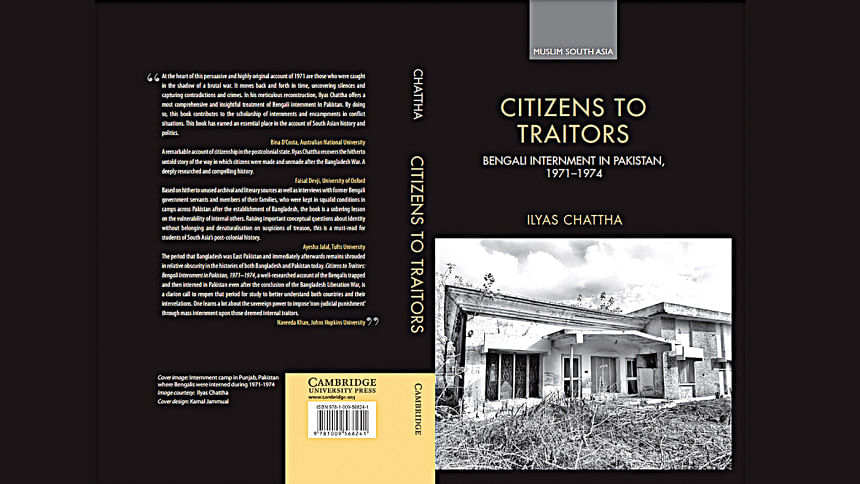

Dr. Ilyas Chattha is a Fellow at Oxford University and Professor of History at LUMS. He is the author of Citizens to Traitors: Bengali Internment in Pakistan, 1971–1974 (Cambridge, 2025).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments