Puthi

Imagine a time when the printing press was not invented. A time when books were nonexistent and language was oral, narratives memorised and passed on from generation to generation solely by word of mouth. As humans evolved so did their means of preservation of thought, ideas -- initially on their cave walls and later on, on barks, dried leaves and bones of animals.

Only a few were enlightened by the gift of reading; for the general populace -- education and the wonderful world of books were a world hidden behind a veil of illiteracy. The advent of the Gutenberg press revolutionised the way knowledge is now being preserved, and disseminated. It is a milestone in human history when knowledge, for the first time, was made available to the common people.

Although the exact date when the printing press came to Bengal cannot be ascertained, as early as 1847 a press was operating in Rangpur, from where a weekly magazine -- Rangapur Barttabaha, was printed. However, we have a thousand-year-old history of written heritage.

Manuscripts or puthi, as they are called, has a long-standing position in our lives; people gathering around an elderly villager reciting verses from a puthi in a lyrical tone is an image impressed forever in our minds; although it is an image almost none of us have ever encountered.

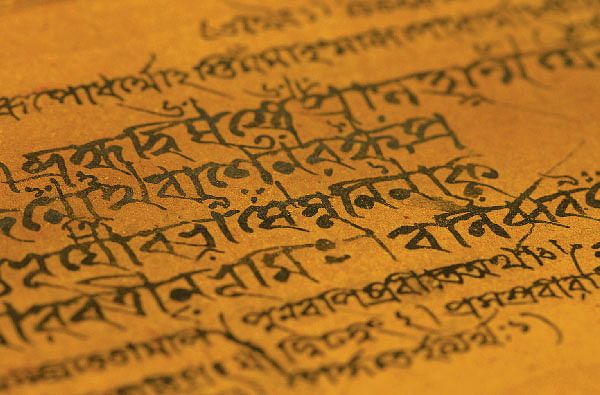

Puthis were written on parchment, leather, leaves, barks, and other materials available in nature. However, to impart longevity these materials were processed through dipping into boiling water and drying subsequently. In the process, the material turned grey or pale yellow and became resistant to insect infestations. And hence the word “pandulipi”-- pandu being the Bangla word for 'pale yellow' and lipi for 'writing'.

The oldest puthi in the collection of the Dhaka University is Saradatilaka dated 1439 A.D. and written on a bark. Puthis common to this region are mostly written in Sanskrit or Bangla, but almost inevitably all are written in the old Bangla script.

The scribes of the old times were respected people who earned their livelihood by penning puthis. In the Hindu community they belonged to a specific cast and were known as “Sharma”. And then there were Muslim scribes.

A scribe had to have the adequate knowledge of the script to execute a fine work of copying manuscripts; knowledge of the language was not a prerequisite but an added advantage. Although they were supposed only to copy the puthi, some of the scribes made some interpolations, resulting in textual variants.

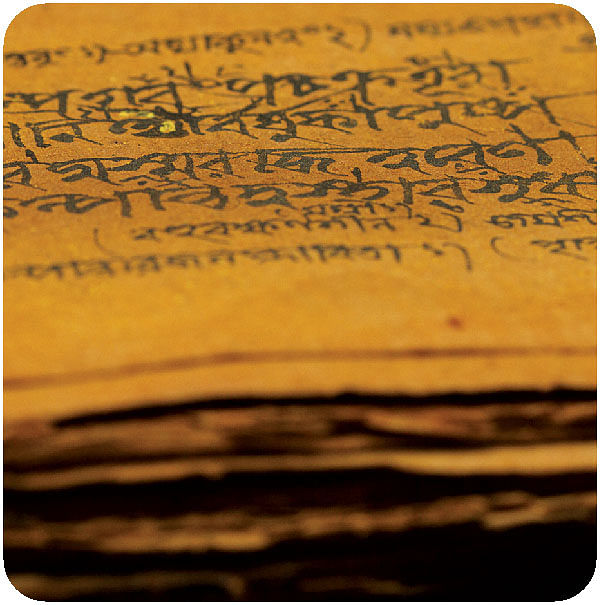

Once complete, many of the scribes wrote their names, occasionally providing a few autobiographical details and the date of the work. The sheets of the puthi were tied together with a piece of string passing through all of them. Two boards would be placed at both ends, often with intricate designs drawn on them.

The part of a puthi where the scribe provides a brief autobiography, the name of the puthi, the date of writing/copying, the name of the person who employed him in the work and for whom the copying is done, is called the colophon or puspika which literally means, floret.

The post scripts deserve due mention in the analysis of a manuscript as these inscriptions were often the most significant aspect of the puthi.

In one of the puthis now residing at the DU Archives, one Ramalochana Sarma who scribed Kautukaratnakara, the manuscript of a Sanskrit play, wrote: “This Ratnakara is copied by Ramalochana Sarma with utmost care. The onus of correcting the spelling lies with the pundits” in Sanskrit.

Another manuscript in Bengali, also in the DU Archive, mentions: “I'm Abdullah's son, a humble man. I hail from the village of Haola. I've copied as I've seen. Excuse my negligence.”

But some scribes did not stop just there. They further enhanced their prized copies often cursing people who steal manuscripts, a trait still as common today as it was almost five hundred years ago.

A scribe writes – “The book is written with utmost care. The mother of the man who steals it is a sow and his father a donkey.”

Some scribes were so attached to their work that they would put postscripts, “To the one who holds this, I say: a book is like a soul, say the wise men.” And then there were cryptograms, where the scribe wrote the date of the manuscript in an encoded puzzle.

Today, hundreds of years after they were penned, old Bengali manuscript are museum pieces. When we see them in archives or in special exhibitions, we stop and wonder at the impact they had in the preservation of ideas in our culture.

Puthis have a glorious past, just like printed books. With the advent of digital technology it is possible that within our lifetime, books may become museum pieces too. But books, just like puthis, are a wonderful creation of civilisation and no matter how far and wide we venture out, they will forever remain special.

Photo: Sazzad Ibne Sayed

Source: Banglapedia

Special thanks to Syeed Bin Salam for allowing us to photograph the puthi from his collection.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments