A Tale of Two Standards

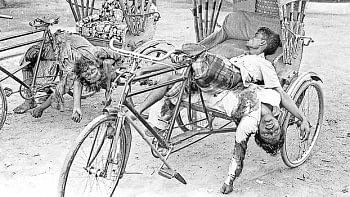

When the tragic Rana Plaza incident occurred on April 24, 2013, the entire international readymade garments (RMG) community cried out loud—and rightly so—about the abysmal working conditions in Bangladeshi apparel industry. In an article in Time magazine on July 11, 2013, a broadside was launched that Bangladeshi RMG workers "perish on the job with depressing frequency". Then in May and July 2013, we saw the formation of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh (Accord) and the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety (Alliance) respectively—two multi-stakeholder governance programmes that worked towards a safer RMG industry in Bangladesh. There is no gainsaying that both Accord and Alliance have done good things for the RMG sector in Bangladesh.

However, it is equally true that steps taken under the Accord and the Alliance were possible because of the influence exerted by Western buyers over Bangladeshi factories. Noted management consultancy firm McKinsey & Company wrote in its 2011 survey report that price attractiveness was the first and foremost reason for Western brands purchasing in Bangladesh. To put it bluntly, Western brands can dictate the pricing terms of a contract with Bangladeshi factories.

Enter Covid-19 in 2020—with teetering economies and trembling infrastructure. Bangladeshi RMG sector has already reported an estimated USD 3.17 billion worth of orders being cancelled. Many international brands are raising defences of force majeure and frustration of contracts under Covid-19 to get out of their obligations, the legality of which is a subject matter of deep discussion in itself.

Recently, however, it has been reported by Reuters that Western brands that agreed not to cancel orders due to Covid-19 epidemic are demanding price cuts of up to 50 percent. The news report also quoted Rubana Huq, president of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), as saying, "We are still observing their departure from original contract terms ... which includes renegotiating prices as low as 50 percent of the original deal."

It's important that we explore the legality of such a stance by the foreign brands. It is true that a contract can be altered by mutual agreement of the parties (see section 62 of the Contract Act 1872). But here, the issue is not about mutual alteration of a contract. The problem lies in the bargaining power of the parties and the context in which such a bargain is made by a party. And at the heart of that context are the principles of economic duress and undue influence.

First, let us start with some general principles. As a matter of law, no contractual bargain—however hard it may be—which is the result of the ordinary interplay of forces will be declared invalid. For example, if a poor man agrees to pay a high rent to a landlord, then the law will not interfere on the ground that it is an unfair bargain. In the eye of the law, the man's impecuniosity will not be a defence in a case by the landlord for non-payment of rent. The decision to declare such a bargain illegal is left to the Parliament.

But every law has an exception. There are cases where courts will interfere and set aside a contract if it can be shown that the parties have not bargained on equal terms—where the bargaining power of one of the parties is so strong and the other's is so weak that, as a matter of fairness, the court will decide that the strong should not be allowed to push the weak to the wall.

One such example is the case of "undue influence". For example, an employer—the stronger party—employs a builder—the weaker party—to do certain work for him. When the builder finished his work and asked for his payment, the employer refused to pay unless he was given some added advantage, like a discount. It may well be that in order to pay his employees, the builder agrees to such a discount and revision of the original contract. It has been observed that the court will set aside such a contract executed under pressure by the weaker party. This principle is codified in section 16 of the Contract Act 1872.

In this type of cases, the common undercurrent is "inequality of bargaining power". It has been held by the courts that when there is inequality of bargaining power in a contract that is grossly underpriced, the law gives relief to the one who executes such a contract, when his bargaining power is seriously impaired by his own needs, coupled with undue influence by or for the benefit of the counter-party.

Here, it should be remembered that the word "undue" does not mean the existence of any wrongdoing. Rather, it refers to the self-interest of a contracting party who is indifferent to the distress he is causing to the other party. On the other hand, a person who is in extreme need (for example, of money) may knowingly consent to a most one-sided bargain, only to get himself out of such financial peril.

But when the stronger party takes advantage of the economic pressure of circumstances, rides onto it and forces the weaker party to revise a subsisting contract, such conduct no longer remains reasonable and the court will strike down such conduct. Covid-19 has created a dire economic situation in the global trade and business. Nonetheless, just because there is economic uncertainty does not mean that a party can renege and walk away from a subsisting contract. The demand by a Western brand, being the dominant party in a RMG contract, not to cancel orders in exchange of price discount due to Covid-19 reeks of such an attitude.

What could be done by Bangladeshi RMG factories in such a situation? What if factories agree to revised contracts with discounted price to tackle their own financial pressure of paying the workers? Can they challenge such contracts after receiving the discounted payment from the buyers?

There is a legal maxim—"No person can insist on a settlement procured by compulsion". A Covid-19-induced factory closure and business disruption can be labelled as "economic compulsion", which can be validly raised by RMG factories that are saddled with revised contracts by Western brands with discounted price. In other words, Bangladeshi RMG factories may be able to recover the price under the original contract on the ground of "economic duress" if it could be shown that the revised contract is executed against a threat of the Western brand to break the original contract.

But it should be remembered that the RMG factories relying on "economic duress" must first rescind the revised contracts and demand the balance price under the original contracts (see section 66 of the Contract Act 1872). It is essential to do so because under section 19A of the Contract Act 1872, a contract that is executed under undue influence is "voidable" and not "void", which means the revised contract must be rescinded by the party relying on "economic duress" once the facts surrounding the duress cease to exist.

The proposed price cut by Western brands through revision of subsisting contracts with RMG factories has been a tale of two standards. On the one hand, Western brands wailed at the Bangladeshi RMG industry's state after the Rana Plaza collapse and worked commendably through Accord and Alliance towards improving workers' safety. On the other hand, in these testing times of Covid-19, the brands are threatening to walk away from valid contracts if heavy discounts are not offered by RMG factories which, as Reuters reported, would be "heaping economic pain on a country already reeling from the crisis."

In the wake of the Rana Plaza tragedy, Bangladeshi RMG factories had nothing to defend themselves. But this time, the law is by their side.

Junayed Chowdhury is an Advocate of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh and the Managing Partner of Vertex Chambers.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments