When faith is a weapon, don’t be surprised by who wields it

A dramatic turn of events since the March 17 attack on Hindu villagers in Sunamganj's Shalla Upazila has been reshaping the narrative on the culpability of potential actors and, by extension, the politics of communal violence in Bangladesh. On Saturday, police arrested Shahidul Islam Swadhin, the prime accused in two cases filed over the attack. Until then, the narrative was quite simple: supporters of Hefazat-e-Islam, incensed by an alleged Facebook post by a Hindu young man criticising their leader Mamunul Haque, carried out the attacks. No ulterior motive. No political machinations. Just the work of some run-of-the-mill fanatics out for revenge. The simplicity of the message meant that the "liberal right"—the so-called liberal supporters of the political right—could safely denounce religious fanaticism without being pulled into awkward questions about Hefazat's tryst with the ruling establishment.

But Swadhin, a UP member who even newspapers loyal to the government identified as a Jubo League leader, threw cold water on that narrative. According to The Daily Star, Swadhin allegedly orchestrated the incident by gathering Hefazat supporters over the said Facebook post and then led a mob that went on a rampage through the village. About 90 Hindu houses were damaged or looted as a consequence. Now, timeline it with what we came to know about Swadhin's past records—his feud with the Hindus of the Noagaon village in Shalla over fishing in a nearby jolmohal, his deliberate attempt to deprive them by stopping the flow of water and pumping it out and taking all the fish forcibly, the fines he had paid for his actions—and an ulterior motive presents itself. This led political opponents to openly hint at an AL/Jubo League connection.

The turnabout in narratives is as dramatic as it is significant in understanding communal politics in Bangladesh. It offers important lessons about the need to investigate the build-up to such cases of violence. It would be wrong, however, to suggest that such violence is always manufactured to serve vested interests. The threat of religious intolerance leading to spontaneous communal violence or other faith crimes is a real and dangerous one. And a crowd that supports persecution of religious minorities is perhaps as much to blame as the crowd that carries out the persecution. But we live in an environment that allows religion to be exploited for personal, political or economic interests, and it can open up a whole gamut of possibilities which we should be ready to accept.

Unfortunately, after nearly every such violence, we're given only half the picture: that of a blood-thirsty menagerie of wild zealots seeking revenge for a supposed assault on their faith, as if no other scenarios may exist. Rarely are such crimes investigated with an intent to get to the bottom of them and to bring the real culprits to justice. And rarely, if ever, do these investigations end in convictions, a major reason why the crimes keep happening.

At this point, we must acknowledge that Facebook or social media has added a new, very dangerous dimension to the conception and commission of communal violence, which should worry the policymakers. Consider four cases from recent history: On November 1, 2020, 10 Hindu homes were reportedly vandalised and torched in Cumilla. On October 20, 2019, over 13 Hindu homes were similarly attacked and a temple destroyed in Bhola. On November 10, 2017, at least 30 Hindu homes were burned to the ground in Rangpur. On October 30, 2016, over 100 Hindu homes and 17 temples were destroyed and 100 Hindu individuals attacked in Brahmanbaria. All these attacks were carried out by crowds outraged over Facebook posts, real or fake, allegedly "demeaning Islam".

The poor, helpless souls at the receiving end of these heinous crimes in the name of religion are yet to get justice. Will they ever? Will the Shalla victims? Will the victims of other types of communal violence? It may be impractical to hope so, despite the assurances of the higher authorities. But even if they do get justice, how much of an impact will it have on religious freedom in a country that still officially prefers one religion over all others, where there is little tolerance of diversity in general, and where a curious interaction of faith, politics and economics has somehow made cultivation of intolerance a very profitable project for all parties involved?

The Swadhin case in Shalla can be seen as a template for how this interaction plays out. It entails a political link-up with faith crimes to serve a vested interest. Researches of communal violence in Bangladesh highlight two major motivations for such link-ups: 1) grabbing the land, properties and businesses of members of the minority communities (religious, language or ethnic); and 2) political/electoral calculations. There can be other motivations but these two remain a major influence, and we have seen how often violence took place with the provocation, explicit or implicit support, leadership or at least consent of the political leaders. Like Swadhin, the names of many local leaders of mainstream parties have also come up in connection with attacks on minorities.

The link-up with faith—and like-minded faith leaders—offers rich dividends in communal politics. Faith, to the beneficiaries of communal violence, is a weapon to be used at will. It helps to whip up anti-minority prejudices and mobilise support for any potential move on the minorities with trumped-up charges like "hurting religious sentiments", "demeaning Islam or the Prophet" or, as in Shalla's case, "insulting an allama". To these people, it matters little if the minorities are really guilty as charged. It matters little if the alleged acts are punishable offences. It matters little that an entire community or group cannot be punished or held responsible for one person's "crimes". It matters little that those meting out the punishment have no authority to do so. It matters little that minorities, too, are citizens, with equal rights and deserving equal access to the services, opportunities and protection this country can offer.

But communal provocateurs don't thrive on facts or questions of morality. They thrive on mischaracterisation and dehumanisation of the minorities. Swadhin, as one of them, is rather a small fish in a big pond—the politics of divisions, "sentiments" and communalism is playing out on a national stage today. But he amply shows why we should critically probe the inner dynamics of communal violence and never let any narrative go unscrutinised.

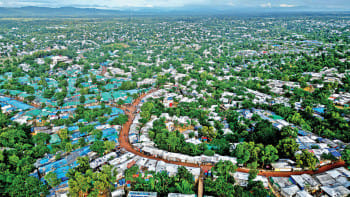

In Shalla, the irony of what happened couldn't be starker—here is a place that, until recently, was better known for being the birthplace of BRAC, where Sir Fazle Hasan Abed launched his post-war nation rebuilding work in 1972. The love that once flowed through this region and gave hope to an entire nation seems to have been replaced by fear, hatred and bitterness. How this transformation came about should be studied and learned from, if we are to stop this rot from spreading far and wide.

True, the public can be easily manipulated with the fear of an imaginary threat to their faith or community, and we have to continuously work on developing inter-faith and inter-community trust and respect for diversity so that they find a peaceful way to communicate and resolve their differences. But those who try to exploit people's emotions to stoke communal unrest—politicians, community/faith leaders, and other actors—are a bigger threat here. We need to see them for what they are. We need to stop them from weaponising faith. Unless we stop this destructive interplay among faith, political and economic interests that has taken root of late, the casualties will only pile up, further destabilising our already deeply fractured society. The responsibility to ensure it doesn't happen rests squarely on the government.

Badiuzzaman Bay is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments