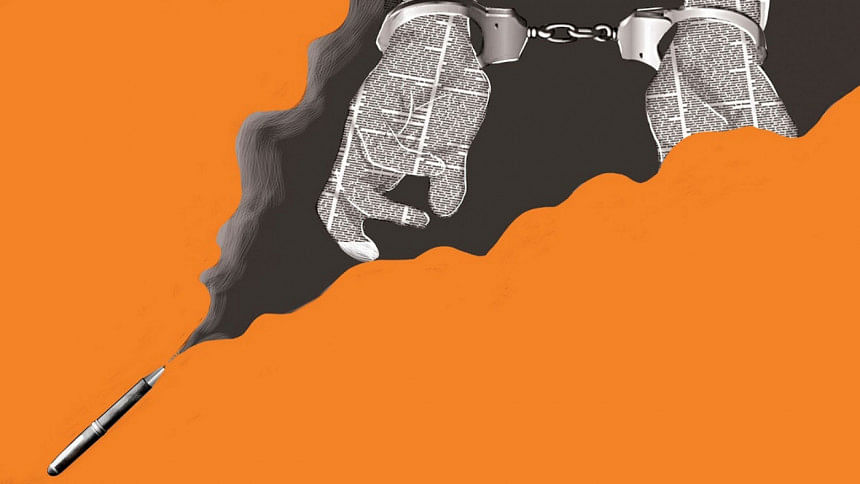

Journalism remains fraught with risks and persecution

For 45-year-old Ilias Hossain, there was nothing unusual about October 11—until things took a deadly turn. On his way back from work, Hossain was brutally stabbed and then left on the street to die in a pool of his own blood. His fault? He was a journalist who had exposed the crimes of a local drug and illegal gas connection racketeering gang. Hossain's report had landed two brothers—Tushar and Turjoy—from Narayanganj in jail. Upon securing bail, the brothers decided to settle their scores with Ilias.

Post the gruesome killing of Ilias Hossain—correspondent for Dainik Bijoy, a local Bangla daily—three people have been arrested, including Tushar. But five other accused remain at large. And there remains the possibility of this case getting buried under the growing pile of unresolved cases in the country, of journalists getting victimised.

The gruesome murder of journalist couple Sagar Sarwar and Meherun Runi—the brutality of which shocked the nation in February 2012—is a case in point. The couple's five-year-old son discovered his parents' dead bodies in the morning. The then home minister had confidently vowed to catch the killers within 48 hours. Those 48 hours never ended; eight years into that dreadful incident, investigators are yet to find who killed the two and why.

And not just murders, journalists in this country face persecution in many forms and scale. According to a report by Reporters Without Borders—also commonly known as RSF (Reporters sans frontiers)—titled "Bangladeshi reporter slain by local gangsters in Dhaka suburb", published on October 12, 2020, "at least 16 journalists have been the victims of serious violence in Bangladesh since the start of the year."

The RSF report—although alarming—comes as no surprise. On April 19, 2020, the police registered a case against the editor of an online news portal, along with three others—Mohiuddin Sarker, acting editor of jagonews24.com, Rahim Suvho, Thakurgaon correspondent of the online news outlet and local journalist Shaown Amin—under the draconian Digital Security Act, after the news-portal reported on the misappropriation of relief funds. The report apparently had "false, offensive and defamatory content". The person who filed the case was affiliated with Baliadangi Upazila's Swechchhasebak League in Thakurgaon.

This—unfortunately—is not an isolated incident, rather it is symptomatic of the systemic suppression of free press in the locality. According to a Daily Star report, police in Thakurgaon "assaulted the district correspondent of Bangladesh Pratidin and private TV channel News 24 at a checkpost." On April 15, the police sued Dainik Odhikar's district correspondent for "criticising the district administration on Facebook." And Forum for Freedom of Expression, Bangladesh data suggests that around 20 journalists were "attacked, intimidated, harassed, or arrested for reporting on pilferage, corruption, and lack of accountability in food aid meant for the poor during the lockdown", as mentioned in the above cited report, published on April 29, 2020.

And the country is familiar with the sudden disappearance of Shafiqul Islam Kajol, photojournalist and editor of fortnightly magazine "Pakkhakal", who reappeared after 53 days in police custody. According to reports, a defamation suit was filed against Kajol under the DSA on March 9, on the 10th he vanished. As per a report by CIVICUS—an international alliance of civil society organisations and activists to strengthen citizen action—"Human rights groups believe he was subjected to a suspected enforced disappearance." Kajol was slapped with four cases, one also suing Motiur Rahman Chowdhury, prominent journalist and editor-in-chief of Bangla newspaper Manab Zamin.

Apart from these, there have been numerous incidents of journalists being subjected to attacks and harassment across the country since January this year. For instance, in Sylhet, Mahibur Rahman, chairman of Aushkandi Union Parishad in Nabiganj—who also happens to be a ruling party local leader—assaulted district correspondents of three news outlets—Dainik Protidiner Sangbad, Dainik Amar Sangbad and private TV Channel-S—with a cricket bat because they reported on irregularities in relief distribution in the area during the Covid-19 general holidays. The Dainik Protidiner Sangbad correspondent, Shah Sultan Ahmed, had sustained critical injuries and had to be taken to Osmani Medical College for treatment.

Also in April, Golam Sarwar Pintu, a journalist of a Bangla daily, Dainik Bangladesher Alo, had been arrested by the police in a case filed in Dhaka under the DSA by an influential ruling party leader, Sheikh Salim. Pintu had reported on the protests by poor people in the locality seeking food aid during the Covid-19 general holidays.

The growing tendency to systemically suppress free press is not unique to Bangladesh. From the United States to India—two of the more powerful democracies in the world—to the more repressive regimes across the globe, the fourth estate is at risk of being smothered. And with governments assuming more powers to restrict the movement of their citizens in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, organisations such as RSF fear that the media might be suppressed further.

"The coronavirus pandemic illustrates the negative factors threatening the right to reliable information, and is itself an exacerbating factor. What will freedom of information, pluralism and reliability look like in 2030? The answer to that question is being determined today," said RSF secretary-general Christophe Deloire.

In the context of Bangladesh, the DSA is an additional mechanism that makes sure journalists stay within the line. It is unfortunate, how an act that was supposed to have enhanced digital security of citizens is apparently being used to deprive them of correct and unbiased information.

On this International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists—in the midst of such uncertainties and unpredictability—one can only hope that governments would realise the folly in suppressing free press. A country without a strong fourth estate is a country that is vulnerable to exploitation. In order to overcome the unprecedented challenges that are being posed by the ever-spreading pandemic, governments should support free press in their quest for truth and accountability. Without having unbiased information about the state of affairs, are we not hamstringing our own exit out of this pandemic?

Governments, that define themselves as democratic especially, across the world, are obligated to ensure the security of journalists and to carry out vigorous investigations when crimes are committed against them. Thus impunity for crimes against journalists must end. Governments must stop the state-sponsored agencies from victimising journalists, which would send a strong message to the other actors—politicians, criminals, vested groups—who are engaged in such criminal activities. They should also fast track the disposal of cases for crimes against journalists and bring the criminals to justice—irrespective of their identity and/or political affiliations. Instead of clamping down on journalists, governments should hunt down those criminals who are involved in the suppression of freedom of expression.

But to be able to do this, governments need to overcome their inherent fear of truth and accountability. Governments must realise that truth will not always go in their favour, but they need to know the realities nonetheless to address the problems facing the people, especially in times such as these. And it is only through a strong fourth estate that governments can access unbiased information. And it is only when journalists are allowed to do their job without fear that democracy can thrive.

Tasneem Tayeb is a columnist for The Daily Star. Her Twitter handle is: @TayebTasneem

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments