Let's be prepared rather than wait for the doomsday

INTENSE urbanisation and industrialisation over the last four decades have caused drastic changes in Dhaka in terms of environmental components, topography and population density. Once one of the most beautiful cities of the world in the 16th century, it was ranked second from the bottom (139th) among the global cities in The Economist Intelligence Unit's Global Liveability Index (GLI) (The Economist, 2014).

If this is not enough to be alarmed and jump into action without any delay, there is more to add to the dismal scenario. Bangladesh sits where three active tectonic plates meet including the presence of historical seismicity and a plate boundary in the east and several faults in and around the country. While Bangladesh has been extremely fortunate not to be hit by a major earthquake in the last 85 years or so, the chance of a major earthquake is looming. In a blog in 2011, Kevin Krajick, Senior science writer of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, fears that "the next great earthquake" is "lurking under Bangladesh". He refers to a continuing study led by seismologists at the Earth Observatory in conjunction with Dhaka University, including specialists from Vanderbilt University, the University of Minnesota and Queens College, and researchers in Germany, Italy and India. According to a report published by the United Nations IDNDR-RADIUS Initiative, "Dhaka and Tehran are the two cities with the highest relative earthquake disaster risks". It is not a question of if, but when.

An earthquake of 7.5 magnitude in Dhaka city, originating in the Madhupur fault, would damage around 150,000 buildings and moderately damage around 241 hospitals and clinics. About 90 schools would be destroyed while 30 police stations and four fire stations would be moderately damaged. At the same time 10 hospitals would be destroyed. The instantaneous death toll would be 61,000-88,000. The capital has 13 fire stations and 10 of them, constructed in the 1960s, are more vulnerable. The economic loss would be US $6.1 billion in the capital city —almost 50 per cent of the nation's annual budget in 2009 (Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme, UNDP: 2009). Since disruption shows little correlation with physical damage, the outbreak of disease, disruption of lifeline services and the suffering of people may be very great.

While the general people may not be fully aware of the risk of earthquake, how would one define the role of the policymakers, real-estate businessmen and their employees (which include engineers), educated land owners and government officials (building construction authority, lifeline and health services)? Are these people aware of the laws and the consequences of non-compliance? Are the key agencies and sectors like Fire Service and Civil Defense (FSCD), health sector (government and private), DESCO, Titas Gas, NGOs adequately prepared to serve the people in an earthquake emergency? If not, does the authority have an adequate plan or ongoing activities regarding post-earthquake emergency services? Are they factoring the earthquake risk adequately in their plans and activities?

It appears that the related authorities and stakeholders—the implementers of the building code, the agency primarily responsible for rescue including those in the health sector—are not prioritising earthquake risk sufficiently. Slowly but surely, Dhaka city is becoming a death-trap in the case of a seismic disaster. Is it ignorance or greed in terms of promoting individual interest? Or is it the fact that they think an earthquake disaster is inevitable and so just continues to act as usual? Or is this non-response of the concerned agencies a matter of 'socially organised denial'?

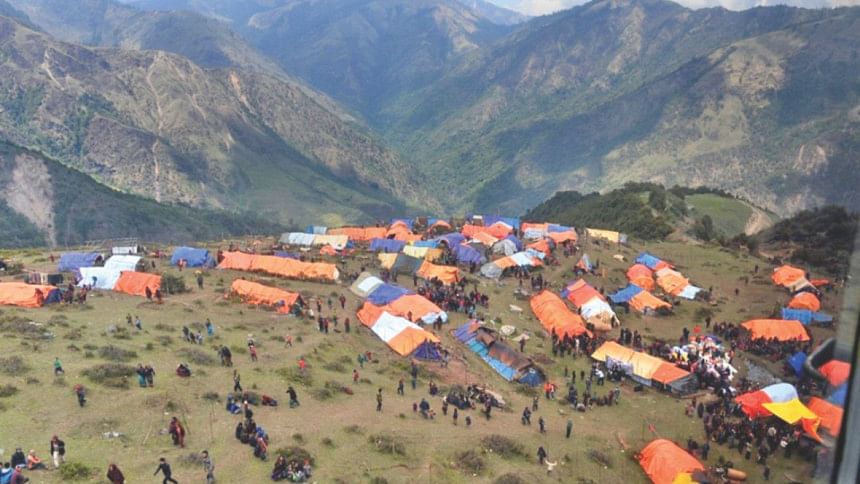

As we generally find after any disaster, the loss of thousands of lives and unprecedented suffering caused by the April 25 earthquake in Nepal and the subsequent tremors felt almost all over Bangladesh have reinvigorated the issue of poor earthquake preparedness in Bangladesh, especially for Dhaka city. Can this be a real wake-up call for us? We have enough knowledge and information to take some steps right away. All we need is the will to do the right things and perform above individual interest to make the necessary preparations to substantially reduce suffering and loss of life in a post-earthquake situation.

The classic examples of good preparedness (Chile in 2010, Japan in 2011) and bad preparedness (Kashmir-Pakistan in 2005, Haiti in 2010) show us that following some basic rules matter a lot. It is not only about having most modern rescue equipment, the main preparedness for earthquake lies in steps that involve strict enforcement of building codes, good governance and less corruption, established preparedness curricula in schools, protocols drawn up for earthquake response including a point-person for international relief efforts , search and rescue teams equipped and trained adequately, exploring efforts against soil liquefaction to reduce building collapse, retrofitting of existing structures and demolishing risky buildings which are not worth retrofitting.

If we are really concerned, then it is high time that we translate this concern into action. While coordination of all the government and non-government actors is essential in this regard, the first step would be to stop with the shifting and rejection of responsibility and recognizing the individual's role in reducing the risk. In order to break the deadlock, a psychosocial approach should aim to link our thinking or experience with the social and political context of Bangladesh. We also need to generate an active consensus in favour of taking effective action to bring about earthquake mitigation and preparation.

The writers work for James P. Grant School of Public Health at BRAC University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments