Pinter, Huntington and gaps in the drawing rooms

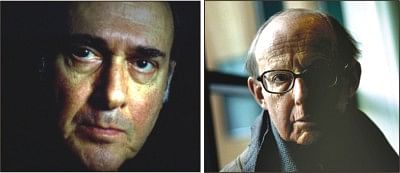

Harold Pinter (left) and Samuel Huntington (right)

Two men, one a Briton and the other an American, died on Christmas Eve 2008. Harold Pinter probably did for English drama what few have done. Indeed, it was said of him that he did to plays what Auden once said should be done. He cleaned the gutters of the English language, so that afterwards it flowed more easily. And so on and so forth. By the time he died at seventy-eight, Pinter had turned into a rounded character, in that particular phrase normally reserved for individuals peopling drama. He was a dramatist, he was a critic, he was a polemicist. That last bit came off rather strongly, and to the delight of many, when he accepted the Nobel Prize for literature in 2005. He excoriated the Bush administration over its adventures abroad.

That surely did not earn him plaudits in Washington, but Pinter was one man who simply did not care what others thought of him. On television talk shows, he rudely and rightly put down men who had associated themselves with the Bush administration. The sneer said it all. Hearing Pinter then, and watching his expression, made you realise how politics could come to be dominated by philistines. The English playwright brought out the hollowness in all the men and women who formed what perhaps will go down as the worst White House in all of American history. The BBC might engage you on the motion of George W. Bush being the worst president in United States history. But the idea of it came a lot earlier, with men like Pinter and the Australian journalist John Pilger ready and willing to strip pretension to its absolute naked form. It is a good thing that Karl Rove and Bill Kristol, both fervent believers in the 'wisdom' of George W. Bush, never bumped into Pinter, or into involved writers like him.

Harold Pinter will be missed. And one of the reasons why is that the end of his life brings to an end the remarkable intellectual partnership he had forged with his wife, the historian Lady Antonia Fraser. Back in the days when they fell in love (and it created quite a scandal), the more discerning of observers saw in the blossoming romance a perfect blend of analytical minds -- Pinter's focused on the politics of his times, Fraser's on the conflicts of lost ages.

And it is this question of ages, of civilizations as they have straddled the globe that takes hold of you when you speak of the American who passed into the ages on Christmas Eve. Samuel Huntington has in these past many years been famous or notorious (it all depends on how you view the march of men through the deserts of time) for his seminal work, "Clash of Civilizations". So what was so important about the work? Simply this: Huntington refused to go along with the view propounded by many that following the collapse of communism it would be a unified world order, underpinned by democracy, that would bring happiness to people. He went back to history, into things of an atavistic nature, and emerged with the idea that local tribalisms, as propounded through religion or tradition or both and indeed everywhere, would be the new universal reality.

If you go back to what has been happening across the world since the early 1990s, you cannot really be dismissive of Huntington. After Iraq, after Afghanistan, after the crusading zeal in which America's neo-conservatives have gone to work and now, in light of what the Israelis have been doing in Gaza, you realise the profundity that defined Huntington's intellectuality. He was one of the few men who knew what a post-Cold War world would look like. In that respect, his foresight clearly left Francis Fukuyama's End of History reflections far behind.

Huntington was eighty-one when he died. Life for him, against the backdrop of the reputation he had developed through his teaching and writing, had truly turned out to be fulfilling. In the 1960s, as a young intellectual, he was dispatched to South Vietnam by the Johnson administration to assess conditions on the ground. Huntington lost little time in concluding that the war was not going well for Washington. Earlier, in the 1950s, he served as a speechwriter for Adlai Stevenson, the thinking man who did not make it to the White House. And in 1968, as Hubert Humphrey struggled to beat Richard Nixon at the election, Huntington served as a foreign policy advisor to him.

Death is diminishing for those yet living. The passing of Harold Pinter and Samuel Huntington leaves huge gaps in the drawing rooms where culture once flowed freely, almost rhythmically.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments