A researcher’s journey to the frozen continent

Fairuz Ishraque, a Bangladeshi scientist, recently journeyed to the icy continent of Antarctica, where he spent 69 days conducting research in the Allan Hills, a notable group of hills in the region.

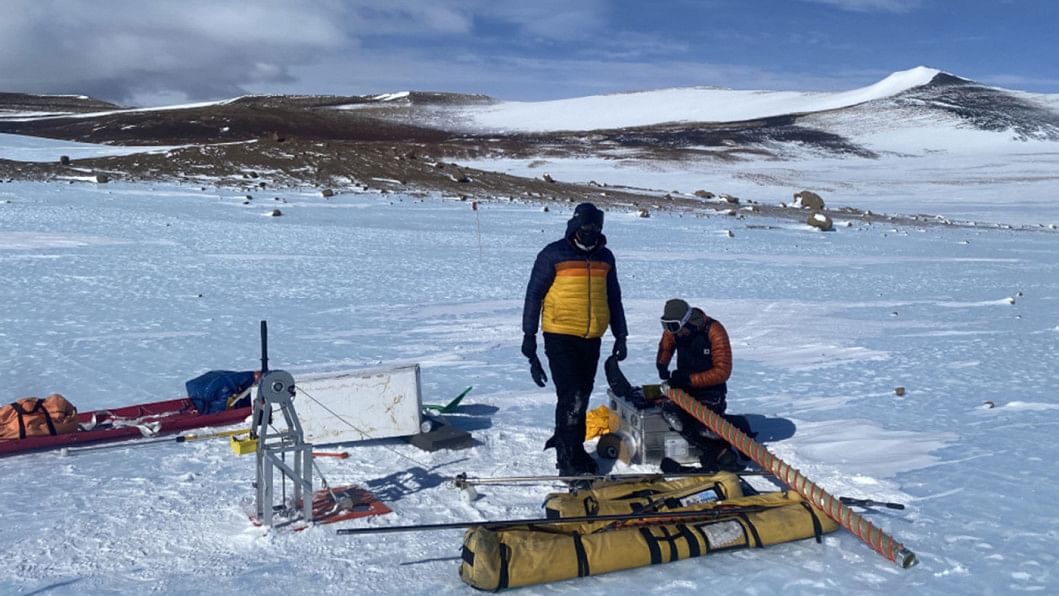

During that time, through his exploration and field activities, Fairuz gained hands-on experience about how research is conducted in the region. His research was part of the US Antarctic Program.

After he returned to the US, The Daily Star sat down with Fairuz for an exclusive interview for insights into the secrets that lie deep inside the icy regions.

The Daily Star (DS): Could you tell us about your research experience in Antarctica? How does one even begin to make their way to Antarctica?

Fairuz Ishraque: From the US we went to Christchurch, New Zealand. We stayed there for two days in the US Antarctic Program clothing distribution centre (CDC) to get necessary gear like jackets, boots, pens, etc. The flights from New Zealand to Antarctica are highly dependent on the weather and the conditions of the runway. There are two ways to get there, either on a C130 small aircraft or a C17 cargo flight. I went in a C17 aircraft, which took six hours to get to the McMurdo station in Antarctica.

There, we received training in McMurdo station for one week before heading to Allan hills. Overall, I was there from November 17, 2024 to January 24, 2025.

DS: What was your initial reaction upon arriving in Antarctica?

Fairuz: From McMurdo station, the Allan Hills are across Transantarctic Mountains. There is typically no wildlife there for around 300 miles. An initial challenge for me was adjusting with the fact that there is no "night time" in that region of Antarctica during the summer because of the high latitude. Also, summer time in Antarctica usually starts in October and ends in March, which in itself can be odd. So, not only did I have to get used to a "summer season" where temperatures were negative 30-40 degrees, but I also had to get used to having no typical "night time". Also, in Allan Hills, there are extremely high winds as fast as 80 kilometres an hour. The atmosphere is completely dry, with no humidity. So everything felt upside down.

TDS: What piqued your interest in researching Antarctica? Could you provide insights on your research?

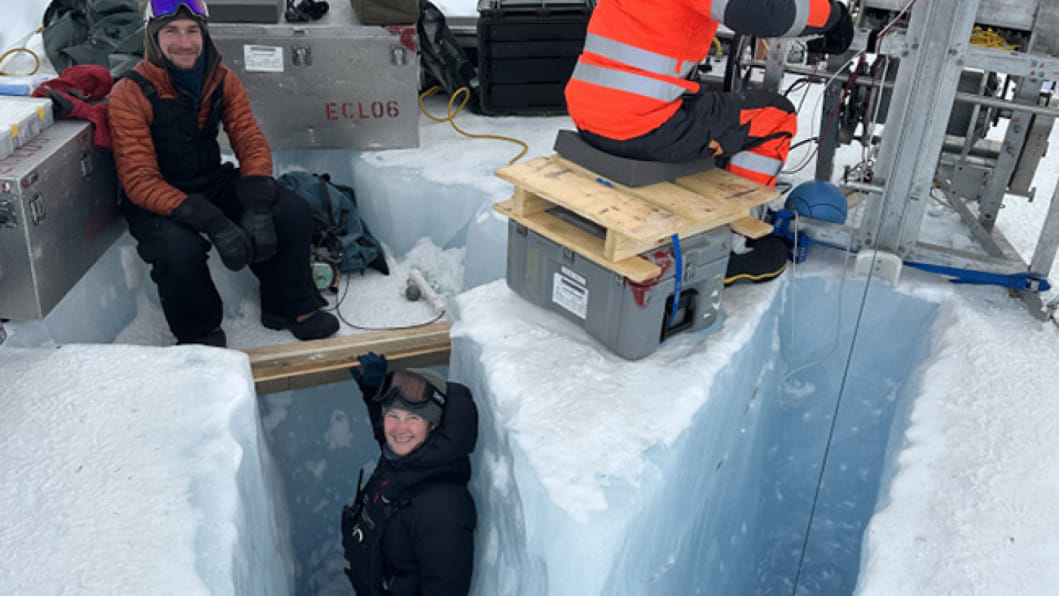

Fairuz: We are interested in the Allan Hills because of ice cores that can be found there. Ice cores are like cylinders of ice drilled out from the ice sheets. They serve as a really good record regarding climate change from the past.

Different chemicals and gases are trapped in the ice as it settles in Antarctica. More and more ice settles on top and mixes till it almost becomes like sedimentary rocks made of ice and various chemicals.

I am a part of The Higgins Research Group which drilled and collected ice cores from here over the last decade. Because of these ice cores, we have a really good idea of what the Earth's atmosphere looked like around 8,00,000 years in the past.

However, the Earth's geologic and climate history goes back billions of years. Unfortunately, ice sheets are usually only thick enough to fit 8,00,000 years of information.

What makes Allan Hills special is because it is one of the few locations at the periphery of Antarctica that traps really old ice as it flows from the centre of the continent to the edge. These are called "blue ice areas". Blue ice areas are special in the sense that the ice we get from that area sometimes holds even more information within the ice.

Generally, when drilling an ice core, an ideal location would be further inside the continent, somewhere like the south pole where the ice is two kilometres thick. There, you would have to drill 2 kilometres to access that information and that's what we have been doing for the last two decades.

TDS: How does your work with ice cores contribute to our understanding of past climate conditions?

Fairuz: With the ice cores collected from the field, researchers are able to run chemical analysis. We melt these ice cores and they contain "bubbles" which tell us atmospheric compositions from the past. We are essentially creating a timeline of the earth's atmosphere.

The main reason we need to do this is because it's extremely hard to make predictions about climate change in general. The Earth's climate system is complex and it's a chaotic system. If you try to make computational models of it, they would never tell you the same thing every time you run it. The way to get around that is to understand what happened in similar situations in the past.

Behind today's climate change situation, the main culprit is carbon dioxide, which is rising due to human consumption. In earth's history, there were similar instances in the past. One of the main examples can be the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) which happened around 55 million years back.

These are events in our history which are very similar to what is happening now. By using these ice cores, which contain records of these incidents, you can see how the atmosphere reacted to these changes. -- what happened to the sea levels, ocean circulation, atmospheric circulation? Did we have more storms or more typhoons in the past? We can make and understand these connections from the chemistry that are kept recorded in these ice cores.

TDS: As you are drilling for ice cores, is there any harm to the ecosystem while conducting research in Antarctica? What kind of equipment do you use?

Fairuz: Primarily, we do not have worry about the ecosystem as there are no living beings in most of interior Antarctica. However, when you are drilling really deep, like two and a half kilometres deep, it can become tricky. There are rivers and lakes under the 3 kilometre mark. The last thing you want to do is to drill into a river. Because we use an oil-based lubricating fluid for the drilling, which can contaminate the water system under the ice if we drilled that far.

Generally, when we drill ice, the small cylindrical holes we make, also known as boreholes, close up within a year thanks to the movement of the ice sheets. If anyone drills through the ice and hits the water in a river underneath the ice, it could cause significant damage to the ecosystem.

Thankfully we have a lot of safety measures so that does not happen. Also, Allan Hills is so far on the edge of the continent, the ice sheet is not deep enough. So, we only drill through about 200 metres of ice at a time.

TDS: Is there any military involvement with this field research?

Fairuz: Similar to the sixties space race between the US and Russia, the same race is happening for ice cores. Europe has the longest ice core in the world and that puts pressure on countries with major scientific interests to have the same ice core records. So, there are also national interests alongside scientific developments. However, according to the Antarctic Treaty that was signed by all countries active in the icy continent, military activities are prohibited. Antarctica is supposed to only be used for scientific research.

TDS: Currently you are a graduate student at Princeton University, pursuing your PhD. But what inspired you to choose this career path?

Fairuz: I completed my SSC in 2015 and HSC in 2017 from Chattogram Cantonment Public College. Afterwards, I got admitted in the department of Geology at the University of Dhaka for an undergraduate degree.

But after five months, I received a full-ride scholarship to study at Colgate University in the US. So, in 2018 I came to America.

I was very interested in participating in Olympiads when I was a high schooler. In 2016, I represented the Bangladesh team in the International Olympiad on Astronomy and Astrophysics (IOAA). I also became a part of the National Earth Olympiad in Bangladesh. I was part of the national team for the International Earth Science Olympiad (IESO) in Japan in 2016. In 2017, I was a team leader for the Bangladesh team in the International Earth Science Olympiad in France. I learned a lot from these Olympiads and from my peers at that time. These experiences led me to pursue a career in science.

TDS: What are your future plans?

Fairuz: I want to finish my PhD, complete a postdoctoral research, ideally in a setting where I get to do ice core field work and analysis with computational models. Eventually, I want to try to get to a faculty position where I can develop and lead my own Antarctic field research.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments