Satyajit Ray and the stories he tells

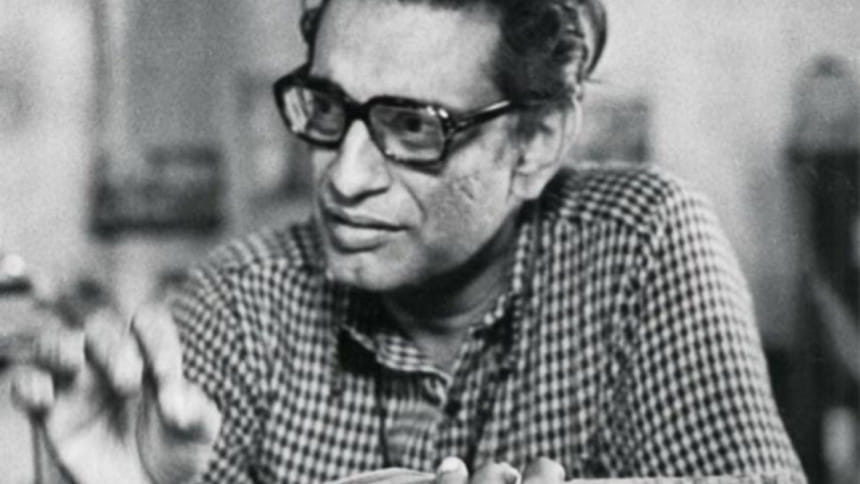

What do you call a person who has multiple talents? A filmmaker, who writes his own stories and screenplays, who contributes to the background score and is an illustrator as well, who gets involved hands-on in the minute details, such as a mural that will appear only for a second in his film or an illustration of the opening and closing credits? Someone who commanded authority on the set, who was suave in both panjabi-pyjama and a tailored jacket, an embodiment of Feluda himself, or Manikda, as he was fondly referred to by his colleagues and peers—or Satyajit Ray, as the world knows him.

Satyajit Ray, born on May 2, 1921—a hundred years ago from this day—hails from a long line of Rays. His grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray, was the first storyteller of the family, followed by his father, Sukumar Ray, master of the fun and formally experimental verse fondly remembered as HaJaBaRaLa, a children's novella often compared to Alice in Wonderland. Any Bangali would be lying if they said they did not come across one of Satyajit's works during their childhood or adolescence, be it one of his short stories, such as "Brown Shaheb-er Baari" or "Sahodeb Babu'r Portrait" (you can find the TV adaptation on YouTube), or Goopi Gayen Bagha Byen's iconic Bhooter Raja (King of the Ghosts), whom Ray himself voiced, or the memory of Kishore Kumar singing "Ogo Bideshini" in the classic film Charulata. Indeed, it is impossible to deny Satyajit Ray's contribution to Bangla cinema and literature.

Whenever I think of Ray, I find myself overwhelmed with nostalgia. His books were a major part of my childhood, and they contributed to the values that I hold still as an adult. Being an Indian, Ray took elements of multicultural, post-partition India and dichotomised them in his stories. A great example of this would be his 12-minute-long short film Two (available on YouTube), which tells the story of two boys, one living in a building, the other in a small hut. The two boys duel using the collection of toys each possesses, as a bid to outclass the other, with the rich boy's expensive toys defeating the latter's kites, flutes, and other handmade wares. Yet the poor boy retreats to his hut with his flute under an open sky, while the rich boy stays confined in his flat, alone, with only his battery-run robot for company. The robot walks unguided right into the tower he built, crashing it like a house of cards.

In this way, Ray's stories addressed the elephant in the room, exploring how poverty, inequality, corruption, colonialism, caste-based segregation, childhood experiences, and the changing world affected the middle-class Bangali in the early 20th century. Mental health, consumerism, and the dynamics of socio-economic status often made their way into Ray's complex works. While these issues are still being addressed by different schools of thought, Ray chose storytelling as his medium to dissect them in a language readers and viewers of all ages and cultures would understand and find relevant, even after half a century since their original release.

In many ways, I believe Ray played a pivotal role in shaping me into the adult I became. His stories made me curious and more accepting of new ideas, of the idea that life is neither white nor black, nor right nor wrong, and how a little bit of patience and tolerance will allow us to venture into avenues we did not know existed. One of my personal favourites from Ray's body of work is Agantuk (The Stranger), a story of a long-lost uncle, Manmohan Mitra, played by the legendary Utpal Datta, visiting his niece and her husband and son. The niece and her husband are sceptical of Mitra's identity as he had left home at a very young age, and thus could be an impostor. The film raises more questions than it answers about how the very notion of civilisation needs to be revisited and revised, and how religion often segregates, even among the very people who practise it.

Ray is still loved and revered both in Bangladesh and in West Bengal. Ananda Publishers owns the publishing rights in Kolkata, while in Bangladesh, Nalonda have recently released a nine-volume Satyajit Ray collection, which includes his complete set of short stories, Professor Shonku, and all the novellas of Feluda. Conversations on these collections thrive in Bangladesh's online book communities, including Litmosphere, Bookstagram BD, and Thriller Pathokder Ashor on Facebook. With the release of the new Feluda web series Feluda Pherot directed by Srijit Mukherjee, the popularity of Satyajit Ray is still at its peak, operating in the legacy of five different Feludas played by Soumitra Chatterjee, Sabyasachi Chakraborty, Abir Chatterjee, Parambrata Chatterjee and this year, Tota Roy Chowdhury. Fifty years after its time, Feluda continues to stand the test of time.

To me, personally, Satyajit Ray is special because in his works, I find friends I may not have seen in years and places I had visited once and long to return to. Even if you do not identify with any of these feelings, I am sure you will at least find yourself in one of Ray's tales.

Redwan Islam Orittro is co-founder of Bookstagram BD on Facebook, part part-time digital media advertiser and a full-time reader. You can check his book blog on Instagram @the_manwholovedbooks.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments