‘We are the 95%’: Bhashani and the Kagmari Festival

In 2011, people reclaimed the streets, parks and public spaces in major financial districts across the world as part of the Occupy Movement. "We are the 99%" was the popular slogan of the movement, coined by the anarchist anthropologist David Graeber and others. The movement occupied space, amplified marginalised voices, and reimagined a new world, necessitated after the 2007-8 global financial disaster had rendered visible the damage inflicted by the wealthy few on the rest of the world. This was, of course, not the first time that the demand for the world to be reimagined in different ways had been made. This article revisits a moment in South Asia when something similar happened.

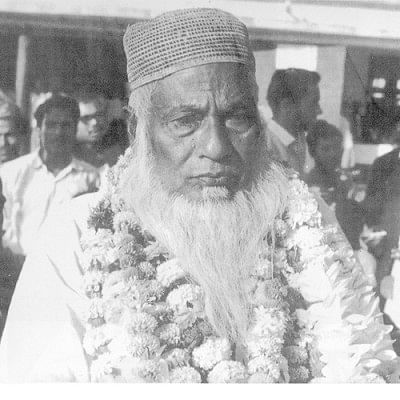

On the occasion of the 140th birth anniversary of Maulana Bhashani, I wanted to re-examine the 1957 Kagmari Sammelon—the event that signalled the break-up of the Awami League and the birth of the National Awami Party (NAP)—and argue for its uniqueness as a political event in postcolonial South Asia. The Kagmari Sammelon was the festival of the "95%".

In early 1957, Awami League held the reins of power at the Centre and in the Province, the only time this would happen in the pre-71 history of Pakistan. Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy was the Prime Minister of Pakistan, and Ataur Rahman Khan was the Chief Minister in East Pakistan. However, this power had come at a cost, a U-turn, in fact, on the party's position on autonomy, complete withdrawal from bilateral and multilateral security agreements, and a free and independent policy. On the other hand, Maulana Bhashani's commitment to anti-imperialist and Third World solidarity politics had strengthened. The people, he argued, could not be the "masters" of their destiny if they were also the "talpi-bahok" (porters) of imperial powers. Bhashani planned an event that would overpower and undermine Suhrawardy's onward march in defence of security pacts and bolster his demands for love and friendship in the newly decolonised Afro-Asia bloc.

So he called out to the "95%"—"poor cultivators, labourers, blacksmiths, potters, etc." and "all those with whose money the country runs"—to attend the Awami League Council Convention in Kagmari in February 1957. These were not the typical attendees of a convention, but Bhashani did not intend for the Kagmari Sammelon to be a typical run-of-the-mill political gathering. It was a uniquely disruptive political event, invariably described as a mela (festival), sanskritik sammelon (cultural gathering) and "Afro-Asian cultural convention". The Kagmari Sammelon disturbed the traditional arrangement of power and politics, democratised spaces, and population, and opened up new ways of sensing, relating and inhabiting the world. Over the course of six days, conversations on Cold War in the Third World, military pacts, and anti-imperial and decolonial futures—usually confined to parliament chambers, university halls, debating clubs and mansions of Dhaka—migrated to the rural maidan (public space) of Kagmari, foregrounding the participation of those excluded from the formal spheres of politics. It was in these unlikely settings that the demand for radical anti-imperial friendships and solidarity with the Third World triumphed over the case for more arms spending and military pacts. The subaltern was not the parochial subject, nor the elite the international elite actor as traditionally imagined.

How was this done? Kagmari was the enacted vision of a world turned upside down, dramatising the power and equality of those who had come to be ignored by those in power. Those who organised and attended the event described how the ojparagaon (backward village) transformed into an osthayi rajdhani (temporary capital) over this period. This was not just a remark on the thousands of people that descended onto the small village, including the Prime Minister and the Chief Minister of East Pakistan, politicians, international guests and foreign diplomats, but a reference also to the infrastructural and aesthetic makeover that the village underwent. The sights, sounds and smells normally associated with the small towns or villages in East Bengal were not to be found over the duration of the festival. Instead, what the residents and attendees encountered were road networks leading to a well-lit village connected to the electricity grid, constant supply of clean water, latrines which produced no strong and strange odours, huge furnace ovens used to cook food fit for foreign guests, and medical arrangements on standby. The estate of the former Maharajah of Santosh, unused and abandoned since the Partition, recovered some of its old lustre and glory in its new role as the actual site of the Sammelon. This is important because the rural village, which during the colonial era had captivated the anti-colonial nationalist imagination, lost much of its political importance in the postcolonial period. The dominance of the urban over the rural was apparent in East Pakistan by the mid-1950s. In September 1956, as villagers poured out of boats and ferries onto the riverbanks of Dhaka to take part in a hunger march, the police fired shots at them. The city was where people now came to articulate basic socio-economic and political claims and be seen by the modern state.

The changing infrastructure and aesthetics in Kagmari—the village that turned capital—presented a vision of the power and possibilities contained within rural spaces and constituencies, a role otherwise denied to them. Kagmari was a rebuke to those in the power, who thought politics could only happen in modern spaces. Bhashani, through Kagmari, had shown that peasants, and other marginalised constituencies, were as modern, progressive and capable of political thought as their urban and elite counterparts. The Sammelon was a manifestation of Jacques Ranciere's "principle of axiomatic equality—the equality of anyone with anyone", a space of radical equality.

However, Kagmari was not just about the re-ordering of spatial and temporal configurations of power, but also the articulation of alternative left subjectivities, communities and futures. Bhashani turned Kagmari into a pedagogical space, where rural aesthetics and culture revealed worlds that were radically egalitarian, anti-capitalist and creatively combined vernacular and global ideas and practices of Islam and socialism. Central to the pedagogy was the idea that if people were to see that it was possible to inhabit the world differently, they would want to change it. However, it was not in an abstract way that the world was to be experienced but through local, concrete and visible forms, through things that can be touched, seen, smelt and heard. Bhashani used gates, music and dance to persuade and educate his constituencies.

The gates were one of the most striking sights of Kagmari Sammelon, memorable enough to merit a mention in Sunil Gangopadhyay's epic Partition novel "Purbo Paschim", where one of the main characters attending the event remarks on the "beautifully made gateways". The gates, numbering 50 and possibly more, were more likely the work of Quamrul Hassan, the patua artist and founding member of Dacca Art School in 1948. They had the names of political, religious and cultural figures—including Mao, Gandhi, Haji Shariatullah, Tagore, Stalin and the Prophet—emblazoned on them. There was no serious attempt to organise these gates in order of importance or any other identifiable category. Although it has not been possible to retrieve stories that were told or imagined by subaltern constituencies as they passed through these gates, but as suggested by other historians working on marginal histories, speculation becomes a necessary historical task. It is possible that the arches, a structural feature in Mughal imperial architecture, paradoxically played a similar as well as a radically different function in Kagmari. Historically, they have denoted the king's rule and power and the connection between different spaces. But at Kagmari, the gates were designed to place emphasis on connection between those lifeworlds rather than what divided them, with peasants and labourers being shown that they were part of a wider and richer moral and cultural universe.

Central to the Kagmari narrative is how important subaltern joy was in the thinking and fighting for decolonial politics and futures. Mikhail Bakhtin in his work on Rabelais describes carnival laughter and its "indissoluble and essential relation to freedom". Descriptions of Kagmari demonstrate the carnivalesque nature of the gathering, with people "milling around scores of shops and stalls", people "cheering and watching the fun", ferris wheels, stick fighting, and the singing and dancing. Joy was integral to the experience and intellection of solidarity and internationalism at Kagmari. The physical feeling of collective joy and togetherness generated by the laugher, chattering and hustle-and-bustle offered a physical embodied sense of diverse popular gatherings and the power that a demotic left future could bring to the people.

As Kagmari wound down, the repeated shouting of "long live global solidarity" by peasants, workers and others resonated across the village, signalling a dramatic defeat for Suhrawardy, an outcome he himself later conceded. The Prime Minister of Pakistan was unable to convince the assembled crowd of peasants, workers and other groups of a future at war. Bhashani had turned the villages of East Bengal into a site of defeat of narrow understandings of nationalism or Islam. He had shown how the "95%" were integral to the reimagining of futures based on radical egalitarianism, Afro-Asian love, and vernacular socialism.

Some of the most important progressive political moments of recent years have come from occupied space: Shaheen Bagh, Tahrir, the Indignados movement. These and other creative protests have reworked and combined existing cultural forms for progressive ends. With Kagmari we see a unique South Asian example to draw energy and inspiration to renew efforts for rebuilding our world for the many and not the few, a demand more urgent than ever.

Layli Uddin is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at King's College London. She is currently working on her book on the making and unmaking of East Pakistan, examining the role of Maulana Bhashani and peasant and worker mobilisation. This article is an abridged excerpt from her chapter in the forthcoming book "Forms of the Left: Left-Wing Aesthetics and Postcolonial South Asia".

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments