Transition of power

The 15th amendment of the Bangladesh constitution is perhaps the most debatable one in the post democratic era that follows the 1990 public upsurge against autocracy. The often pronounced justifications offered for this amendment is the 'needs' for returning to the spirit and contents of the founding constitution of 1972 of Bangladesh. Yet the 15th amendment rather accommodates some of the changes brought out by the 5th and 7th amendments, both made by the Martial Law regime and recently declared illegal and unconstitutional by the apex court of the country.

15th amendment, like most of the previous amendments, also largely failed to reflect comparative constitutional studies. Such study is considered essential for learning the experiences of constitutionalism in relevant jurisprudences and borrowing or adapting them in amending a nation's own constitution. Although the 1972 constitution of Bangladesh was indigenous in part, the 1972 Constituent Assembly (led by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman) enriched our constitution by the same process of borrowing and/or adapting from models and concepts of foreign constitutions. For example: collective responsibility of ministers to Parliament and functions of parliamentary committees were taken from UK system, the concept of fundamental principle of state policy from India and Ireland, the provisions of human rights and Judicial review from US constitutional jurisprudence.

Such borrowing is a recognised practice partly due to the fact that the functions to be discharged by a modern state are fundamentally similar all over the world such as legislation, administration and adjudication. A realisation that the goal of divergent political systems is to perform the same functions underscores the needs for enriching a state's own constitution from the experience of comparative constitutional discourses. Unfortunately, hardly any amendment (except, for example, 12th amendment) of Bangladesh constitution has reflected the learning from such experience. The 15th amendment, in a few cases, seems to be aware of the contemporary constitutional developments while it incorporates the provisions for protection of environment and indigenous culture. But as a whole, it has largely failed to learn the spirit of contemporary constitutional journey.

It needs to be mentioned here that the objective of modern constitutional amendment is basically to establish more transparency, accountability, predictability and participation in the governance system. To be more specific, one major objective of a progressive amendment is enhancing and expanding protection of human rights. Examples of such amendment range from the first 10 amendments of the US constitution to the modern practice of incorporation of Gay rights in a few constitution of the West and inclusion of Right to Information in a larger number of constitutions like Belgium, Mexico, Norway, Panama, Philippines and Thailand. Another objective which might have greater positive impact in citizen's life is strengthening good governance through constitutional amendment. For example, 18th amendment of Pakistan Constitution has ensured much more objective appointment in the higher judiciary and in other constitutional positions and later amendment (108-112) of the Indian constitution has strengthened the local government structures and protection and participation of disadvantaged people. Another recent trend of progressive amendment is to provide enforceability to social, economic and environmental rights. Example includes the 1996 South Africa Constitution and inclusion of right to safe drinking water in constitutions like those of Ecuador and Costa Rica.

Unfortunately Bangladesh has taken a different path from more common global trend. The first amendment of the constitution was made in 1973 for enabling and facilitating the trial of war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity. This is one of the very few amendments which could be termed as a progression of constitutional order and citizen's rights. Most of the later amendments in Bangladesh have been done either to legitimatise illegal regimes (5th and 7th amendment), or monopolising power of the incumbent (4th amendment) or shrinking citizens' rights (2nd amendment) or to ensure re-election to power (14th amendment).

15th amendment, being the most recent amendment has equally frustrated many people. Although it has some positive aspects, the negatives are too many overshadowing the achievements obtained by positive provisions. Its positive aspects include correcting the country's sense of history and identity (for example reinstating the preamble and the four fundamental principles of state policy in accordance with the 1972 Constitution) and reflecting contemporary development (like recognising the needs for protection of environment, biodiversity and cultural identity of ethnic minorities). It has emphasised right of equal opportunity of the women in every sphere of life, returned the right of abstention from voting in parliament in line with Article 70 of the 1972 constitution and revived, although in part, the independence of the subordinate courts in accordance with the 1972 constitution. But it has also retained a number of provisions of the martial law regimes in regard to tenure, mode of removal and post-retirement opportunities of the judges of the superior court.

Such contradiction is more baffling in its provisions in regard to religious identity of the state. The 15th amendment has replaced 'Absolute Trust and Faith in Almighty Allah' with 'Secularism' and revived Article 12 of the 1972 Constitution which prohibits 'granting by the State of political status in favour of any religion'. But quite contradictorily, its Article 2A provides a special status to Islam by declaring it as a State religion, although in a diluted form than the way it was originally phrased by the Ershad regime in 1988.

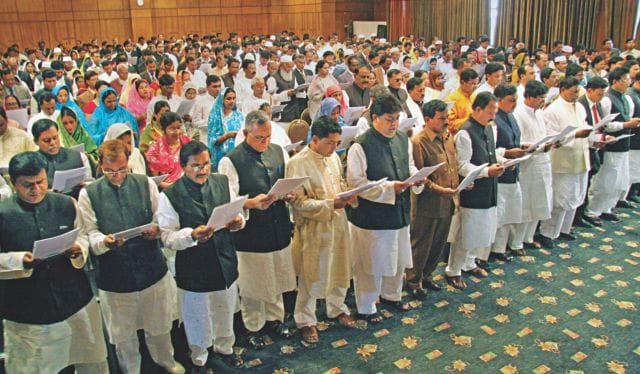

The 15th amendment has added two new clauses in Article 7 which might have significant impacts. Article 7A has declared abrogation, repeal or suspension of the constitution by any unconstitutional means as an offence of sedition. This is definitely a good addition for protecting the constitutional sanctity and democratic transition of power.

But Article 7B introduced by the 15th amendment has created new controversy by illegalising the power and authority of future parliaments in amending nearly one third of the Articles of the constitution by providing that the preamble, fundamental principles, fundamental rights and the provisions relating to the basic structures of the Constitution shall not be amendable by way of insertion, modification, substitution, repeal or by any other means. Arguably, this provision thus has even shunned the scopes for future parliament to restore the 1972 constitution for example by deleting the provisions of state religion or to give enforceability to economic rights like right to education and health. This is also undemocratic in that one particular parliament should not restrain the authority of the equally powerful future parliaments in amending constitution.

The 15th amendment has also repealed the rights of the citizen's to constitution-making by deleting the provisions of referendum on constitutional amendment. The necessity of referendum is getting increasingly recognised in Europe (including in the UK, a country traditionally reluctant to referendum) and also in America. On the contrary, the 15th amendment has snatched the right of participation of people and curtailed such right of their elected representative in amending constitution. It has thus undermined the spirit of democracy.

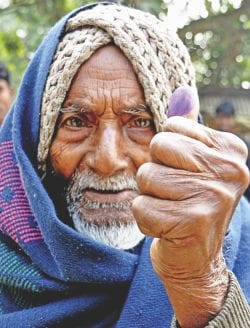

The most controversial aspect of the 15th amendment is its deletion of caretaker government (CTG). The controversy may be explained by taking account of the relation between CTG, election and democracy. In a country like Bangladesh the only scope for the general people of participating in “democracy” comes when they exercise their voting rights once every five years.

A fair counting of their participation through election is a very important concern for every citizen of the country as well as for their political organisations. The ingenious device of forming a non-party caretaker government to guard the sanctity and credibility of election was therefore hailed by majority of the people as well as political parties. In addition to ensuring free and fair election, the caretaker government had gained reputation for significant improvement of law and order situation during their tenure, setting standards of good governance and undertaking pro-people legal reforms, for example in areas of election administration, human rights and anti-corruption drives. Therefore, the scrapping of the caretaker system by 15th amendment had shocked most of the people, citizen groups and political entities.

The CTG however was not immune from controversies. The traditional opposition against CTG was founded on its not-elected nature. Further, the last CTG installed through the 1/11 incidents also underlined the necessity of specific provisions as to it duration, function and jurisdiction. But, these loopholes of the CTG system could have been sensibly resolved through its modifications, not by its deletion. Given its far greater comparative advantages, it is feared that its deletion by the 15th amendment may encourage

more confrontational politics (2006 scenario) or less credible election (1986 and 1996 experience) and destabilise the economy of the country.

The proponents of the 15th amendment often argue that free and fair election could even be held under the incumbent political government of Bangladesh. But we have to agree that conduction of a fair and free election depends on some essential preconditions: powerful and independent Election Commission, healthy political culture, objective media and other observers, independent burancracies, and acceptable law and order situation.

A political government organises the civil and election administration and the law enforcing agencies during its tenure in such a way that these elements work for the incumbent regime during the parliamentary election. Only a caretaker government can break this structure and create a balanced situation for electoral administration.

It explains why election engineering happened more in the elections held under political governments rather than those under caretaker governments. It is important to note that no parliament in Bangladesh established through election under political government has yet completed its full term, two of the heads of government appointed through such election were brutally killed and all of such governments ended up in military rule or popular uprising.

On the other hand, all three governments elected under the non-party caretaker or interim governments successfully completed their full term. It emphatically reflects the comparative acceptability of the elections held under non-party caretaker government.

The present government tends to justify the deletion of the 15th amendment on the ground that the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court had declared the caretaker government as void and unconstitutional in its 13th Amendment case. But if we carefully read the short order of the judgment delivered on May 10, 2011, it still directed for holding the next two parliamentary elections under non-party caretaker government in view of the age old maxims of necessity and safety of the people and the state. In the full judgment released after sixteen months on September 16, 2012, Justice Khairul Haque, in concurrence with the majority of the judges, directed that the caretaker government could be formed only with elected representatives. This kind of deviation without further hearing is unprecedented, and alleged to be violation of the basic philosophy of justice. This deviation has also been pointed out by the three dissenting judges of the Appellate Division and their observation on this issue can be regarded as a significant criticism of the judgment.

The Supreme Court, in its 13th Amendment judgment, has nullified a recognised solution innovated by the politicians by changing its short order in the final judgment. After its judgment, we again face the age old challenges of election under political government. The sense of history, prudence and foresight, if there still is any, of the major political leaders of the country then they could now save us from this crisis.

They should realise that their consensus for a non-party caretaker government is vital for peaceful and democratic transition of power in future. If such consensus could be reached, they may again amend the constitution to establish a different form of non-party caretaker government during election period. The simple device could be forming that government with non-political persons elected through by-elections conducted three months prior to the next parliamentary election. There may be better alternatives as well. But what we need to agree is that the scopes of a smooth and peaceful transition of power should not be obstructed on the plea of the 15th amendment. The interests of people and the state should prevail over an amendment of the constitution which is politically convenient only for the incumbent.

The writer is Professor of law, Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments