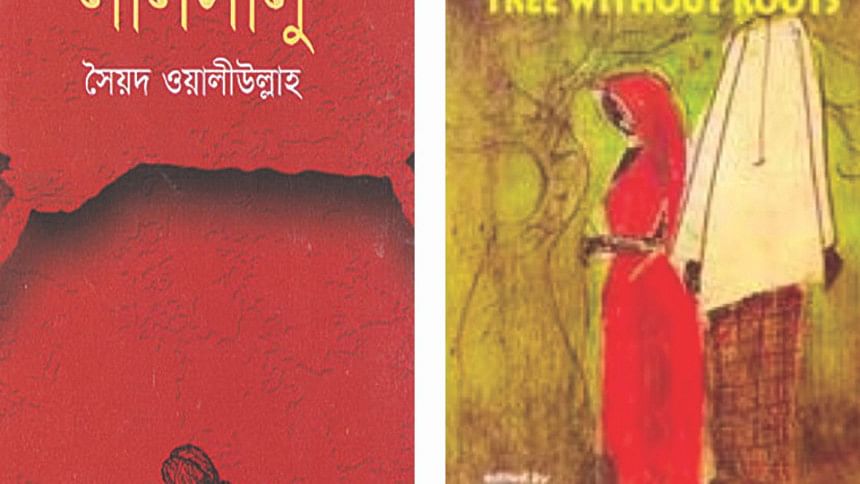

Tree without roots: Lal Shalu Reimagined

Syed Waliullah's Tree Without Roots (1967) is a transcreation (a recreation in another language), rather than a literal translation, of his first novel Lal Shalu (1948). Waliullah made a number of changes to the text when translating it into English several years later. Certain characters and episodes are added or subtracted in the later version. Significant scenes from the original are missing, compelling us to ask why they were neglected. The transcreation also has an extended beginning and ending. Probably, Waliullah's long stay abroad by the time he translated Lal Shalu led to the changes that he made.

Lal Shalu/Tree Without Roots tells the story of Majeed—a rootless man in search of a permanent place to live and prosper. He has long ago left his own village where there are "too many people and not enough food." Too many young men are trained in the maktabs, and when they do not find employment in their own village, they branch out in search of work. Majeed becomes the muezzin of a makeshift mosque in the Garo Hills, but his life is lonely and difficult. He comes down from the hills in search of a better existence and seeks out the grave of an unknown person on the outskirts of Mahabbatnagar in Lal Shalu, renamed Mahabbatpur in Tree Without Roots, transforming it into a mazar (shrine). The mazar brings income for its keeper. People from Mahabbatpur and its surrounding villages come to pray at the mazar; they leave behind coins. Soon we find Majeed, who entered Mahabbatpur carrying only "a kurta, a couple of old lungis, two thin towels and a small, much-thumbed Koran," owning a house, land, cows, and a storehouse for grain. He marries not once, but twice. Hardly ever does anyone question the mazar or Majeed's power. The landowner Khaleque is under his spell; and when Majeed perceives any threat to this rule, he expertly uproots it. It is not till much later, when Majeed remarries, that he meets a worthy opponent. His second wife, Jamila, and the hailstorm toward the end of the novel, collaborate to dislodge Majeed who has "struck his roots deep and firm" in Mahabbatpur. However Waliullah shows us, particularly in the transcreation, that forces like Majeed are not so easily overcome.

Waliullah started writing Lal Shalu not long before the Partition when he was in Kolkata. The novel is said to have been influenced by a mausoleum that the author observed during his childhood in Mymensingh. He finished the novel and published it in 1948 after returning to Dhaka. While intellectual circles at the time were abuzz with debates and discussions on the ongoing political crisis and the Partition, Waliullah portrays the life of ordinary villagers of East Bengal. Would it be too far-fetched to make a connection between Waliullah and his contemporaries? Religious fervour had led to the separation of India and Pakistan, with the Western part of Pakistan taking up political/religious leadership over the East much in the way that Majeed assumes supremacy over the inhabitants of Mahabbatnagar. Waliullah, like other intellectuals of his time, was concerned; but being a creative writer, his expression is more subtle.

Tree Without Roots, on the other hand, was composed several years later, when Waliullah had been abroad for a while, spending time in New Delhi, Sydney, Jakarta and London, before finally settling in Paris. He translated Lal Shalu into English, from which his spouse, Anne-Marie Thibaud, translated it into French. In the course of the personal journeys that the author underwent, some elements of his novel changed.

Among the significant changes in the later version is the omission of the chapter in which Majeed confronts the pir of Awalpur—his professional rival. Majeed, in Lal Shalu, is troubled by waning crowds at his mazar following the arrival of a pir in the neighbouring village, who is said to perform miracles. He goes to Awalpur taking great personal risk, for the pir is surrounded by his followers and goons. There he finds an assistant of the pir claiming that his master can stop time. Majeed judiciously proves this wrong, and returns to Mahabbatpur with the villagers at his tail. The next day, the villagers return to Awalpur with the intention of punishing the charlatan, but they are beaten by the pir's party. Their defeat in this clash, however, matters little to Majeed, for he has won back their loyalty.

While the Awalpur pir is mentioned in Tree Without Roots, the latter's presence does not aggravate Majeed until Khaleque, his patron, shows interest in him. Khaleque had ignored the pir till Amena, his childless wife, instigated him to bring holy water from Awalpur. Amena's request reflects her lack of faith in Majeed's power—Majeed's first wife, Rahima, too is childless. However, rather than facing the pir, Majeed in the transcreation, concentrates on chastising Amena.

Teaching Tree Without Roots has been an interesting experience. My students are enraged that the women in the novel must rely on charlatans rather than gynaecologists. Though access to doctors in remote villages was rare when Lal Shalu was written, especially for women, their rage is greatly justified. Rahima is blamed for the couple's barrenness—a blame she accepts. However, Jamila is also shown to be childless in the course of the novel, attesting Majeed's incapacity. Ultimately it is this "weak female" who is successful in shaking, if not uprooting, the tree that stands firm on its roots, which her male counterparts are unable to do.

A young native of Mahabbatnagar, Akkas, launches a futile attack on Majeed's autocracy in Lal Shalu. The young man has escaped Majeed's influence through his temporary absence from Mahabbatnagar. Outside the village, he has encountered "secular education" and "English education." He regards the maktabs of Mahabbatnagar as inadequate to train the children of his village, and dreams of setting up a secular school there. However, the village elders—Majeed's followers—are against Akkas, and Majeed too would have ignored him had not Akkas been on the brink of receiving government support for his dream institution. In reaction, the self-conferred religious leader calls a meeting at the mazar to discuss the issue. When Akkas arrives, he is rebuked for not having a beard, regarded as irreligious, and therefore as one whose motives are suspect. Majeed then directs the conversation to the necessity of a new mosque in the village instead of a school. Akkas exits the scene and we never hear of him again.

The exclusion of Akkas in Tree Without Roots is shocking. His omission, along with the omission of Majeed's visit to Awalpur, marks a narrowing of the social dimension of the novel and a shift in focus to Majeed—the individual, for in the absence of these important episodes, we miss the chance to examine some pertinent social issues. The first is the prevalence of Majeed and his kind in the then East Pakistan. East Bengal, around the time of the Partition, seemed to have a combination of political, religious, economic and social conditions that encouraged the flourishing of conmen like Majeed and the Awalpur pir.

Tanvir Mokammel, in his 2001 film Lal Shalu, provides Majeed with a mazar-assistant who does not appear in Waliullah's original novel or in the transcreation. When discussing the film with my students, Mokammel explained the presence of this additional character: "Figures like Majeed rarely existed alone," he said. In other words, the conditions of East Bengal then were favourable for the thriving of multiple Majeeds. Poverty coupled with the religious intensity/hypocrisy of the period would have given strength to such desperate men.

Secondly, with the absence of Akkas in Tree Without Roots, we miss out on the debate regarding secular and religious education. Those interested in the topic may look up Abul Barkat's Political Economy of Madrassa Education in Bangladesh (2011). Akkas promotes "English education"—English being the language that would give learners access to the growing world of knowledge and science, and equip them to counter forces like Majeed. The question of education and its impact on our society as a whole is overlooked in Tree Without Roots. Had Waliullah lost touch with the reality of our region since migrating to France? Perhaps, because he either considered such issues irrelevant, or was induced by the pattern of the Western novel to focus on Majeed alone in Tree Without Roots.

Though Waliullah's later novels Chander Amabasya (1964) and Kando Nadi Kando (1968) are set in Bengal, they are hailed as evidence of Waliullah's commitment to existentialism. The influence of Western thought and literature on Waliullah is clear. Lal Shalu too seems to have been re-written in the sixties keeping a Western audience in mind. The elaborate background establishing the poverty of Bengal at the start of Tree Without Roots is not needed for a Bengali audience. Waliullah was either trying to familiarise the Western audience with a situation unknown to them, or trying to catch their attention by feeding them preconceived information. However, this extended opening also serves to create sympathy for Majeed—a man led by gnawing hunger to a profession of tricking others. Majeed, the conman, is the protagonist of the novel. Throughout his exploits, we cling to the edge of our seats, waiting to see how he will overcome one challenge after another.

The constricting of the social dimension in the transcreation has already been noted. In his essay "Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism," Fredric Jameson claims that even the stories of private individuals in "third world" texts represent the "embattled situation of the public third-world culture and society." This statement, though criticised for being too general, is applicable at least for Lal Shalu. The "first world" novel, Jameson further claims, is largely limited to the individual. In the case of Waliullah's work, the change in the title of the novel itself evinces a narrowing from the public to the private, for while "lal shalu" literally refers to the red cloth used in mausoleums, Majeed is the "tree without roots" of the title of the transcreation. Moreover, there is an additional section at the end focusing entirely on him.

Lal Shalu ends with a storm, perhaps intended to destroy Majeed when his fellow human beings fail to exact a suitable punishment. In Tree Without Roots, however, Waliullah seems dissatisfied with this supernatural ending. The transcreation presents a graver conclusion but a more resolute Majeed. Floodwaters follow the storm, engulfing the mazar, the mosque and Majeed's house, and the trickster must work out how to tackle this challenge as he has tackled many before. The answer for Majeed is to stay put. He must not, under any circumstances, abandon the mazar. Earlier that day, Majeed had visited his "friend" Khaleque only to receive a lukewarm response from him. The destitute peasants had also refused to seek consolation from him. Majeed knows that damage to the mazar can be repaired once the floodwaters recede, but he cannot mend the villagers' faith if he abandons the mazar at this time of distress. Leaving his wives under Khaleque's care, Majeed returns to the only place he can call home. Should he survive the flood, surely he will find a convincing excuse for why the mazar was not spared.

There is ample evidence to suggest that Waliullah had not lost touch with our region after all. We know of his attempts to raise support for Bangladesh among French intellectuals in 1971. We also find his keen realisation in Tree Without Roots, to return to the social interpretation of Waliullah's work, that duplicitous figures like Majeed are not so easily crushed, and we must continuously remain alert.

Does Waliullah project the downfall of West Pakistan in Lal Shalu? Does the storm symbolise our liberation struggle? Does he predict, in Tree Without Roots, that fundamentalist forces would soon return? It all depends on the reader's interpretation of the texts. Is Tree Without Roots an "improved version of Lal Shalu" as Serajul Islam Choudhury claims in his introduction to the transcreation? That too can be left to the reader's discretion. No matter what they decide, pitting the two texts against each other makes interesting reading.

Munasir Kamal is Assistant Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

Comments