On Cricket Books, <i>Dadas</i> and St Xavier's…

After a hiatus of nearly three years I've started reading cricket books again. It was Sujit Mukerhjee who started me off with his Autobiography of An Unknown Cricketer, which I picked up for a song at a Nilkhet bookshop. I enjoyed it so much that an urge to again read cricket books descended on me like monsoon rains on Dhaka stadium. The last one I'd read was Pundits from Pakistan by Rahul Bhattacharya, on India's historic 2004 tour of Pakistan. Poor Rahul, who came to Dhaka on a promotional tour, where inane questions by Bangladeshi sports journos at the book launch reduced him to mumbling clichés on sub-continental cricket. Somehow, it put me off cricket books.

Sujit's tautly worded drive woke me up from the slumber. From the cricket books lying in a pile in my room I picked up Rahul's book and read it again. Lovely stuff - a first-rate piece of writing on Partition angst and reverse swing bowling. This time I did note that Rahul was a Bengali, something I wouldn't have cared about during the first go-round. But Sujit's Autobiography had sensitized me to Bengalis writing on cricket. Rahul, though, was from Mumbai, where he had attended St. Xavier's - his author blurb went: "Rahul Bhattacharya was born in 1979, and was a part of a St. Xavier's College team that comfortably failed to carry forward the legacy of Gavaskar and Ashok Mankad." Hmmm, I thought, another Bengali with an English cricket book to his credit. And one that by far was the best one out of India in a decade.

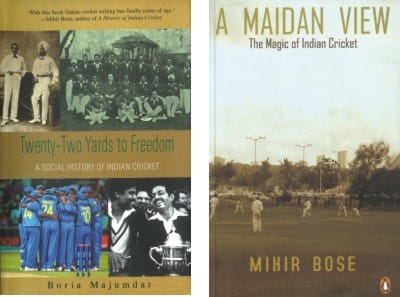

The next book in the pile turned out to be Mihir Bose's A Maidan View: The Magic of Indian Cricket (first print 1986, second 2006). Bose? Hmmm, yet another dada! Mihir I found out is presently BBC's sports editor and has penned quite a few books on Indian cricket. Maidan View is utterly absorbing, Indian cricket seen through a historical-sociological lens. This is not at all as boring as it sounds, since the writing is so deft that I forgot what a dense and thorny subject the book dealt with. It's basically a collection of twelve interlinked essays, among which 'Middle India and the Cricket Raj' is a brilliant sociological study through the prism of cricket of a brash, newly affluent Indian class, inclined at times towards Hindutva and with a gauche love of one-day cricketing 'tamashas'. Another piece, 'The Gali, the Maidan and the Mali,' is a beautifully written, warm portrait of the Bombay of Mihir's childhood as well as of the spaces where Indian cricket gets started. 'Khel Kood as Cricket' rolls up its sleeve to sling into a comparative analysis of Nirad C Chaudhri and the Marxist West Indian author-god CLR James in terms of their critiques of the Empire that is like nothing I've read before. There is a fine essay on Sunil Gavaskar, and while reading it I was startled to find that Mihir Bose too went to school at St Xavier's, when 'Sunny' was there in shorts! So Rahul and Mihir, both Bengalis, both top-grade cricket writers, and though decades apart both products of St. Xavier's…well, well, who would have thought…

Why were the dadas writing such good cricket books all of a sudden? Were they trying to make up for lost glory? I picked up Twentytwo Yards to Freedom: A Social History of Indian Cricket. By Boria Majumdar. Majumdar! Again a Bengali! The book was a distillation of his doctoral thesis at Oxford. Trust a dada to do an Oxford PhD on cricket, when any other self-respecting Indian would have rather shaken hands with a Laskar hood, but that's another story…Boria on Bengal's cricket is fascinating. For example, the Marylebone Cricket Club, founded in 1787, was thought to be the oldest cricket club, but Boria unearthed a 1780 Hickey's Bengal Gazette mentioning "the gentlemen of Calcutta Cricket Club…" thereby establishing CCC as breasting the tape ahead of the MCC. Of course it was sahibs only then. So Bombay has a hallowed place in Indian cricket historiography since it was that city's Parsis, starting around the 1830s, who were the first Indians to play cricket. That was because Parsis felt themselves, like the English, to be a community apart, and wanted to join the elite club of flannelled fools. The Bengali bhadralok, on the other hand, took up cricket from 1870s onwards because he wanted to beat the colonizers at their own game, an anger fueled in part by the imperial typecasting of the Bengali male as effeminate. Funnily enough, the earliest recorded match in Bengal that included 'natives' was in Dhaka in 1876, an account of which is in Muntassir Mamoon's Dhakar Tukitaki. All the 'native' players then were Hindus. Muslim Bengalis, stuck in madrassas and mudflats, do not figure much in Bengal's cricketing tradition or history. In 1947, with the mass migration of Hindus to West Bengal, cricketing talent left too. East Bengal became East Pakistan, and Bengali Muslims for the first time seriously stood on a batting crease, only to face the bouncer of colonial neglect by Pakistan. Despite some good years, the Dhaka League then, with its Independence Cup matches, was a poor cousin to West Pakistan, where Indian Muslim players such as Kardar and Amir Elahi from Bombay and the Mohammed brothers, Wazir and Hanif, from Junagadh had crossed over to renew an old tradition. When Bangladesh emerged, there was no real cricketing history or tradition to build on, which is why that tale of one Bengali, Raqibul Hasan, being chosen to play for Pakistan is told so often. The Bengali Muslim is probably the newest to organized cricket in the subcontinent, and from this historical perspective, Bangladeshi cricketers are subjected unfairly to quick praise or quicker criticism.

Kolkata was the center of Bengal's cricket activity in colonial times, flourishing from 1900 to 1930. Then, due to a host of reasons, it died. The supportive Maharajas of Santosh, Natore, and Cooch-Bihar passed away, the British were leery of giving stadiums and clubs to anushilon-terrorist-breeding Bengal, popular passions shifted to football, and the advent of the Marwaris along with the rise of rural Muslim politicians destroyed the bhadralok cricket-supporting financial base. All this happened as the larger picture changed too, as political power shifted away from Calcutta to Delhi, away from Subhash Bose and C R Das towards Gandhi and Nehru, with Mumbai consolidating itself as Indian cricket's stronghold. After independence the trend continued as the Left began its surge in West Bengal, which cut it off from the center in more ways than one, and throughout the 1950s till the 1980s, outstanding Bengali cricketers - from Shute Banerjee to Shyam Sundar Mitra to Gopal Bose - only played in isolated Test matches on a token basis.

Till the arrival of Sourav Ganguly! And the dadas suddenly began to walk and talk proudly: a Bengali now was India's cricket captain. And its most successful one, to boot!

Funny thing is, he attended St Xavier's school in Kolkata…

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments