The confidence game

AFTER a collective display of complacency throughout most of 2007 and 2008, we are now being counselled by influential international organisations to prepare for a dire economic situation in 2009. With a bumpy ride ahead, we have to fasten our seat belts. Thankfully, they also tell us that we do not have to wear our seat belts for long; the world economy will recover soon. We will witness robust growth in 2010.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) assures us: "Helped by continued efforts to ease credit strains as well as expansionary fiscal and monetary policies, the global economy is projected to experience a gradual recovery in 2010, with growth picking up to 3%."

According to the World Bank's (WB) Global Economic Prospects: "The substantial policy stimulus that has been introduced could cause growth in both developing and developed countries to surge in 2010."

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), shares a similar sentiment: "The upside risks are less significant, but adjustment in bank balance sheets may advance more quickly in response to the comprehensive and unprecedented policy measures introduced. For 2010, widespread risks remain, but these are more equally distributed, reflecting the possibility of an earlier economic recovery."

What are the reasons for this positive assessment? First is their faith that the large stimulus package introduced in the major economies will work effectively and quickly. The second reason can be found in the WB's statement: "Policy makers have now acted forcefully to restore confidence in the international banking system."

This stimulus package may not work effectively and quickly for a number of reasons. This downturn in the global economy is synchronised -- all regions of the world are going down together. So, what is needed is a globally co-ordinated effort to go up together -- which is still absent.

While the advanced countries and some emerging countries have adopted expansionary policies, many others are either unable to engage in counter-cyclical policies because of impaired fiscal and current account balances, or find themselves having to adopt pro-cyclical policies under IMF agreements (as in the case of Pakistan and some East European countries).

As a committee of UN experts on reforms of the international monetary and financial system laments: "There are large asymmetries in global economic policies." These asymmetries, unless attenuated through global cooperation, are likely to inhibit the capacity of the developing region to grow fast enough to compensate for the recession in the G3 (USA, Eurozone and Japan).

Consider also the size, composition and duration of the stimulus package. Many believe that although the stimulus package appears massive, it is still not big enough. According to Paul Krugman: "A number of economists, myself included, think the plan falls short and should be substantially bigger (New York Times, February 7)."

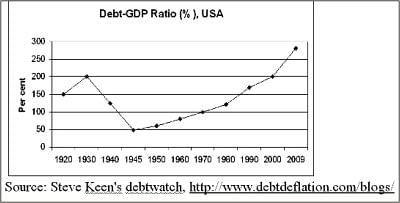

The composition and duration of the stimulus package are important because of the nature and the causes of the crisis. This crisis exposed the unsustainable debt levels of the industrialised economies. As can be seen from the graph, the debt-GDP ratio in the US stands high, higher than the level prior to the Great Depression.

The borrowing binge went on as a false sense of wealth was created through stock and housing market booms. Now with the bubble burst, companies and households are busy trying to pay off their debts to repair balance sheets. So, they are unlikely to borrow any more. This is what Keynes called the "liquidity trap."

For the same reason, sensible households and corporations will use any extra money that they get through tax cuts to pay off their debts. As Paul Krugman puts it: "The point is that nobody really believes that a dollar of tax cuts is always better than a dollar of public spending. Meanwhile, it is clear that when it comes to economic stimulus, public spending provides much more bang for the buck than tax cuts -- and therefore costs less per job created -- because a large fraction of any tax cut will simply be saved (New York Times, January 25)."

Thus, the effectiveness of the US stimulus package, consisting of around 50% tax cuts and direct transfers, is doubtful. An official evaluation of the current fiscal stimulus package as enacted in the US suggests that it will merely mitigate the sharp increase in unemployment (to 7% instead of 8.8% in the first quarter of 2010).

A return to full employment is unlikely before the first quarter of 2014, even if one assumes that the Obama administration will be able to quickly and effectively implement the stimulus package.

As the graph shows, it took nearly 15 years for the debt level to decline to a sustainable level after the Great Depression. While households and companies were repairing their balance sheets, the US kept spending under a new economic deal to make up for the shortfall in demand.

It also took more than a decade for Japan to come out of a similar balance sheet-driven recession. There is no reason to believe that this time round the balance sheet will be repaired soon. So governments around the world must be ready for a sustained period of expansionary policies.

However, from the bickering in the US Congress over President Obama's stimulus package, it seems policy makers are too worried about budget deficits. Thus, we may see a faltering approach to the implementation of counter-cyclical fiscal policies.

The international institutions have the best and the brightest of economists. It is inconceivable that they are naïve and have not allowed for the highly probable pessimistic scenarios that we sketched here. They do admit that the situation is highly uncertain. Yet, how can they be so confident about a turn around within a year?

The answer seems to be in the compulsion that the international organisations feel in playing the "confidence game." The policy gurus in the IMF, the World Bank and the OECD are believers in the power of the stock market and financial investors. If you talk up the pessimistic scenario, it will scare the "rational" investors, which, in turn, will make the downturn inevitable. So, in order to prevent self-fulfilling crises, you have to gain their confidence at all cost.

This is an exercise in what Paul Krugman calls "amateur psychology." It is unlikely to work. The rational investors are smart enough to see the reality and discount the optimism of the international financial institutions. We have seen this time and time again, most recently when the Asian financial crisis was unfolding.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments