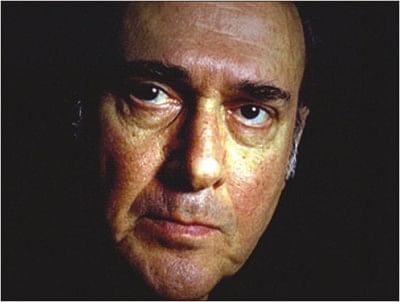

Harold Pinter: Master of menace

Harold Pinter was speaking to the press just after receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2005. "I was told today that one of the Sky channels said this morning that Harold Pinter is dead.' Then they changed their mind and said, 'No, he's won the Nobel prize.' So I've risen from the dead."

So people have been anticipating the death of one of the 20th century's most revered and mysterious playwrights -- the near equal to his fellow Nobelist Samuel Beckett, with plays that achieved far more commercial success than Beckett's -- for quite some time. Now they can stop. Pinter, who had long been ailing from cancer, died on Christmas Eve, at 78.

The most appropriate tribute would be an hour and a half of silence. For Pinter was the master, virtually the copyright holder, of the pregnant pause that never gives birth. Words hurt in his plays, but the withholding of them can inflict deeper wounds, on the characters in his plays and on some of perplexed members of the audience. "Pinteresque" came to suggest an edgy break in an uncomfortable conversation, and the playwright tended to these ellipses like a doting mother. "I did change a silence to a pause," he said about a scene in one of his plays. "It was a rewrite."

In such acclaimed plays as "The Birthday Party" (1958), "The Caretaker" (1960), "The Homecoming" (1966), "Old Times" (1971), "No Man's Land" (1975) and "Betrayal" (1971), Pinter radically altered and energised the traditional dynamic of the stage. It was no longer simply the place where people spoke; it was where not speaking could be far more suggestive, dangerous, theatrical, and eloquent. Like Beckett, he renounced the flossy rhetoric of such post-war playwrights as Christopher Fry and Jean Anouilh for a back-to-basics starkness -- a two-men-on-a-stage simplicity that Aeschylus would have admired. In its citation, the Swedish Academy said Pinter "restored theatre to its basic elements: an enclosed space and unpredictable dialogue, where people are at the mercy of each other and pretence crumbles."

Under all the mysterioso legerdemain, Pinter was the Shakespeare of rhetorical bullying. The bickering men in "The Caretaker" and "Old Times," the quarrelling couples in "Old Times" and "Betrayal," the desperate or rancorous family in "The Birthday Party" and "The Homecoming" -- the rivalries and recriminations of all these mean creatures sparked instant and lasting theatrical pyrotechnics. Who could ask for more of a modern playwright?

He was born on October 10, 1930 in Hackney, London, into what he called "a very respectable, Jewish, lower-middle-class family"; his father Jack was a ladies' tailor. At Hackney Downs School, perceptive teachers nurtured Harold's talent for writing. He was also mad for sports, especially cricket, which would prove a lifelong passion. In his 50s he said that his "three main interests" were family, work and cricket.

Instead of university, Pinter turned to the theatre for his advanced schooling. Hating his time at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (and registering as a conscientious objector when he was called up for national service), Pinter escaped into regional theatre, where he played in repertory for a dozen years. The man who much later reputedly turned down a knighthood rather than align himself with the British government once acted like a baron: David Baron was his stage name.

In 1980 he married the novelist-historian Lady Antonia Fraser.

Like John Osborne, Arnold Wesker, Alan Sillitoe and other novelists and dramatists in what was dubbed the "Angry Young Men" group (after Osborne's 1956 play "Look Back in Anger"), Pinter was not a product of the Oxford-Cambridge factory for leaders in politics, industry and the arts. Being neither born nor bred into the upper class, these writers made class their theme: the resentment and suspicion the unders had for the uppers, which Pinter stripped of overt political references and flipped into the power that one person exercises with cool brutality over another.

Pinter's plays perplexed, not because they withheld information, but because what was on stage didn't always scan logically. In "The Homecoming," for instance: the philosophy professor returns to his boyhood home, bringing a woman he describes as his wife of nine years. Yet his two brothers, their father and an uncle seem surprised at the news. Has the professor been out of touch for so long he hasn't told them he's married? Is she his wife, or perhaps a woman he's engaged to as a test of men's sexual predation? Pinter would tell you to figure it out for yourselves, or don't bother figuring. Looked at today, the play makes perfect sense as Pinter's ribald, misanthropic version of Snow White, with the father and brothers as the dwarfs and the "husband" as her Prince Charming. And the wicked witch with the poisoned apple? Pinter, presenting his play.

Though his plays became sparer and less frequent, he remained an industrious producer of scripts, especially for the movies. Assigned all manner of British novels to adapt, and turned virtually all of them -- "The Servant," "The Pumpkin Eater," "The Quiller Memorandum," "Accident," "The Go-Between" and "The French Lieutenant's Woman" -- into parables of class inequity and betrayed alliances.

"I can sum up none of my plays," he protested. "I can describe none of them, except to say: That is what happened. That is what they said. That is what they did."

In his Nobel speech, which tried to explain his method of evasion, Pinter said: "It's a strange moment, the moment of creating characters who up to that moment have had no existence. What follows is fitful, uncertain, even hallucinatory, although sometimes it can be an unstoppable avalanche. The author's position is an odd one. In a sense he is not welcomed by the characters...To a certain extent you play a never-ending game with them, cat and mouse, blind man's buff, hide and seek. But finally you find that you have people of flesh and blood on your hands, people with will and an individual sensibility of their own, made out of component parts you are unable to change, manipulate or distort."

Pinter did not consider his fellow inhabitants of the world lucky, especially those squirming under tyranny's boot. That sense of moral outrage made his political statements more surgically excoriating. His Nobel speech included a bitter reprise of U.S. foreign policy, which he saw as criminal; and he puckishly offered his services as George W. Bush's speechwriter.

Though it was not his final performance (he did Beckett's monologue "Krapp's Last Tape" from a motorised wheelchair at the Royal Court in 2006), the Nobel speech was the last great play of a man who knew the value of silence, the importance of speaking out.

Source: TIME

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments