US scamster boasted about profit

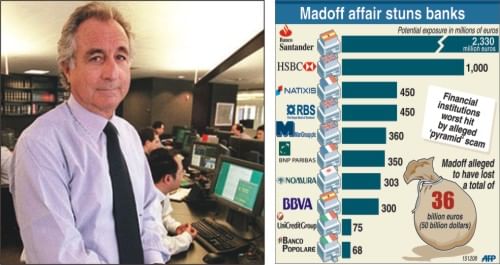

Bernard Madoff (left)

The money manager accused of duping investors in one of Wall Street's biggest Ponzi schemes once boasted to the Securities and Exchange Commission about how much money he earned and formally advised the US government on ways to protect investors from scam artists.

Now Bernard Madoff stands accused of being one.

The 70-year-old Madoff (MAY-doff), well respected in the investment community after serving as chairman of the Nasdaq Stock Market, was arrested last week in what prosecutors say was a $50 billion scheme to defraud investors, including the world's big banks, the rich and the famous.

Alleged victims include the family charitable foundation for Sen. Frank Lautenberg, D-N.J.; a trust tied to real estate magnate Mortimer Zuckerman; and a charity of movie director Steven Spielberg. The Wall Street Journal reported that the foundation of Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel also took a hit.

As the scale of the alleged scheme was realized, attention turned quickly to Madoff's connections to Washington regulators responsible for monitoring investment funds like the one Madoff operated. He knew everyone, former SEC chairman Arthur Levitt said in an interview with The Associated Press. Levitt said he did not invest any money with Madoff.

The director for enforcement at the SEC, Linda Thomsen, said the government was working with federal prosecutors and the FBI to understand the case, "to pursue the case we've got, to preserve assets to the extent we were able and to bring everyone who was responsible for the conduct at the Madoff firm. It's justice," she said Monday.

At one SEC hearing in April 2004 - during the period when Madoff is accused of carrying out his $50 billion fraud - Madoff joked with then-commission chairman William Donaldson about Madoff's own extraordinary profits and teased that he wasn't inclined to provide any advice that might help his business rivals.

"Our firm has made a fairly decent living as a fast market competing with a slow market," Madoff said, "so I'm not sure it's in our own best interest for everyone to become a fast market." Commissioners laughed openly as Madoff agreed "to take off our selfish hats here and speak for the public good."

As a former Nasdaq chairman, Madoff was an expert sought by Washington regulators who asked for advice on any number of regulatory issues over the years. In 2000, Madoff served on the government's Advisory Committee on Market Information, established to protect investors by ensuring accurate and full public disclosure of information to them.

Financial analysts raised concerns about Madoff's practices repeatedly over the past decade, including one letter to the SEC as early as 1999 that accused Madoff of running a Ponzi scheme, but the agency did not conduct even a routine examination of the investment business until last week, The Washington Post reported on its Web site Monday night.

Questions have been raised in two earlier cases about the SEC's handling of investigations involving influential figures on Wall Street or powerful investment firms.

The agency's inspector general, in a report issued this fall, said there were "serious questions" about the impartiality and fairness of the SEC's insider-trading investigation in 2004 and 2005 of hedge fund Pequot Capital Management. A former SEC attorney who worked on the probe and was fired by the agency told Congress he was blocked by agency superiors when he tried to question John Mack, now chairman of the Morgan Stanley investment house.

The SEC took no enforcement action in the Pequot case. The hedge fund and Mack have denied any wrongdoing.

In another report, the inspector general, H. David Kotz, determined the head of the SEC's Miami office failed to properly enforce securities laws in the investigation of now-defunct Bear Stearns' pricing of complex investments it sold, and found that he shouldn't have closed the inquiry in the summer of 2007 without enforcement action.

Bear Stearns nearly collapsed into bankruptcy in March and was purchased by rival JPMorgan Chase with a $29 billion federal backstop.

Last month, an administrative law judge at the SEC rejected Kotz's conclusions and his recommendation for disciplinary action against Thomsen, the agency's enforcement director, and two other officials in the matters. The judge, Brenda Murray, wasn't acting in her capacity as an administrative law judge but rather as an SEC official asked by the agency's executive director to assess the inspector general's findings.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments