Spectre of product fetishism

DHAKA, a city of teeming millions, requires improvements in housing situations. Persistent housing shortagethe gap between demand and supplyis one quantitative aspect of this housing situation. Sustained delivery of affordable and liveable dwelling units and land to all people, then, becomes a priority in housing. A recent initiative for housing delivery is the “Proposal for Comprehensive Housing Development for Dhaka City”, presented at a seminar on 19 June 2008 by Prof. Nazrul Islam and Ms. Salma A. Shafi. They authored 'a vision for housing programme by 2025'; the 'philosophical stand' concerns housing for all, satisfying affordability, equity and environmental sustainability. The proposal was prepared as an 'immediate response' to the desire of the Honourable Chief Adviser to suggest a comprehensive programme for housing development in Dhaka city. Noting several recent events focusing different housing issues, including PRSP 2 initiated and REHAB participated ongoing discussions, a review of this proposal is felt due to contribute to a public debate.

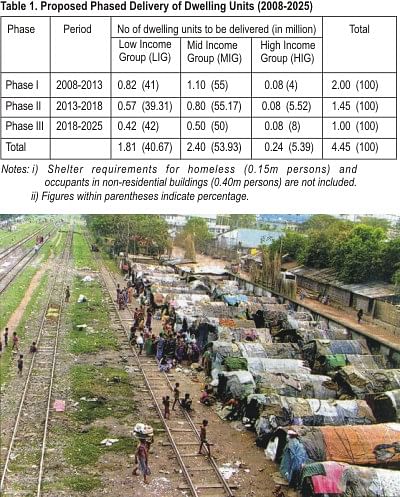

It is much easier to consider housing for a specific social group, be they located at the high-, mid- or low-end of the housing continuum. Housing discourse in Dhaka has mostly been made in this segmented way. But the present proposal for comprehensive housing development is unique in considering the whole housing continuum. The proposal has given emphasis to the quantitative assessment of housing units to be produced in three phases (2008-25) for addressing deficits and existing/future demands (Table 1). Addressing the plight of the urban poor held a special consideration in their proposal, as well as its Phase I implementation. The intention embedded in the proposal, i.e. solving the housing needs of all, may be seen as altruism and questioned on account of realistic means and methods to achieve the set targets. Nevertheless, the comprehensive approach is arguably the way to ensure equity in one's access to housing. Given that, does this proposal really give us a vision as it claims?

The authors have made their proposal a 'production' driven phenomenon with focus on delivering the 'product' (dwelling unit). On the contrary, international wisdom has been arguing since decades to approach housing as a 'process', developing and maintaining a context responsive to housing construction. The process of housing without (delivering) houses has now an established alternative orthodoxy, a way of benefiting maximum people with minimum resources. Enablement, flexibility and participation are the key concepts that drive the process. Government stays away from direct construction while it facilitates others. What their proposal has suggested instead is to focus on the delivery of the physical end product. This attempt of increasing the supply of housing units is a gross simplification of the complex relationship that housing process has, for example, with social, economic, political, and transportation sectors. The delivery of dwelling units is dependent on many different aspects. A note of caution from the open session pointing out the proposal's wished to be autonomous; it is impossible to conceive this proposal without due thought to the provision of water, among others.

Delivery of more than half of all estimated 4.45 million dwelling units (53.93%) has been for the middle-income groups. Their delivery is mostly sought through real estate developers in three phases during 2008-25. This observation is in compliance with the existing trend in the real estate business in Dhaka in terms of its identifying the growing market for the middle-income households. This proposal has actually paved the path for developer led commodification of housing, allegedly initiated in the name of the urban poor, figuring 40.67% percent of all dwelling units. If we take into account the percentage share of LIG (40.67), MIG (53.93) and HIG (5.39) dwelling units, and the respective land they require then we would not possibly get a better picture than those 1980's often quoted figures from Prof. Nazrul Islam's 'unfairly structured city' article. A dissent on the product driven housing delivery is valid so long the Poor's pre-existing inequitable access to land in Dhaka continues.

Inadequacies and inconsistencies that accompany product fetishism, over process, are discussed next to allow me reflecting upon them.

Self-referential and Speculative Projection: The immediate response by the authors can best be considered a speculative projection of how they want the comprehensive housing development to be. Their proposal, in method, content and analysis, remains acutely self-referential without any acknowledgement to the local/international scholarships. They claimed to have had 'consulted' many local documents whose consideration helped making their decisions. A long set of eighteen issues of broader urban sector development policy framework and planning principle were merely listed without explanation. There is, however, a regulation assurance: “In formulating the housing development programme proposal we have kept all the above issues in mind”. But to any sceptical mind, the question is 'where and how' these issues would fit in implementing the proposal? Repeated reminders to the audience about one of the author's previous involvements in major surveys and projects had aimed to get credibility for the proposal. This attempt had appeared hopelessly self-referential instead of practicing the objective rigors one would expect from any academic or practitioner in submitting a proposal of national importance.

Absence of Rationale: The proposal lacks necessary backup theorization that unfortunately dents its credibility. This proposal's coming from the Nagar Unnayan Committee fails to show how housing development relates to Nagar Unnayan i.e. urban development. What would be the rationale, vision for a possible urban development policy in Dhaka is a major question whose omission makes reading the proposal a 'blueprint' to follow. Why would the state engage in what means in housing provision and/or facilitation for the low-income groups, the urban poor in particular? Is this provision or facilitation of the urban poor would take place for the mere reproduction of labour power, for maintaining cheap supply of labour to serve the formal sector economy? To what extent an informal sector housing market remains beneficial to the survival of the urban poor, especially, in a period of acute price hikes of essential commodities to justify an informal housing market's abolishment? These are some of the few critical questions that require due clarification and reflection for outlining a rationale, before formulating and implementing a proposal for comprehensive housing development in Dhaka. Without due clarifications, the proposal remains unanalyzed projection with high risk of worsening the already burdened lives of the urban poor.

Detachment from Practice: The proposal fails to take into account the existing supply and demand side constraints of the crucial land, finance, materials and infrastructure components of housing. Consequently, it falls short on detailing out the housing scenario in Dhaka, especially, in outlining a network with practice. The proposal makes no mention of the roles and responsibilities discrete disciplines/ professions like town/ urban planning, architecture, real estate etc. can potentially make individually and inter-actively. In architecture and urban planning, for example, how 'development planning' and 'development control' mechanisms (by RAJUK) will create a context for and engaging in housing practice is absent. How existing rules and tools on building construction, private land development, wetland preservation and Detail Area Plan (not yet out!) complement each other on issues of FAR, population and dwelling densities remains unaddressed. In this gap, vested interest groupsspeculators and profiteerswould certainly move heaven and earth to manipulate regulatory control mechanisms; the outcomes would compromise public wellbeing and safety for liveable housing environment. The proposal without critical reflections on the past, present and future land developments on wetlands, for example, sends a disturbing signal to the concerned vested quarters, and thereby compromises 'sustainable urban development' for Dhaka city.

Questions not addressed are: from where the land for an estimated 4.45 million dwelling units will come? Has any environmental impact assessment been done? Has any simulation of the infrastructure or transport network serving the added 4.45 million dwelling units been done? The proposal without any reflection on the future spatial implications of the recently approved Strategic Transport Planning appears to hinge toward, if not promotes, the construction sector and land speculation.

Urban Cleansing: The proposal assumes every illegally occupied settlement as potential sites for future housing development after the squatter dwellers' removal (one can use the word 'eviction' in these cases as well) for relocation. Even if we accept on principle that illegal occupants are to be relocated then this relocation does not qualify the subsequent housing development which one might call, after Arjun Appadurai, urban cleansing for alleged greater public wellbeing. The consequence of this urban cleansing is all too familiar around the cities in developing countries. The site of the urban poor fell victim to market poaching, thereby benefits the higher income groups. That the site may have potential non-housing uses, open space for example, for public wellbeing has not been taken into consideration. Korail slum dwellers' not being rehabilitated in Korail, despite initial promise, is a classic example of urban cleansing.

Unqualified Design Precedence and Proposals: This proposal directly concerns the roles and responsibilities of the design discipline/ profession/ institutearchitecture/ architects/ IABof how to create a liveable housing environment for any given group in Dhaka city. Few argue the necessity of air, light and green in housing. On this account, we demand to know, through objective evaluation, whether completed, ongoing or proposed housing projects cited in the Annexure are really worth following in implementing a 'Comprehensive Housing Development' in Dhaka. It remains vague to the present reviewer regarding on what objective evaluation a much criticized project like 'Japan Garden City' had been cited earlier in support of implementing the proposal. This citation exposed the absence of any methodological criteria based on which they could select examples in the Annexure of either precedence or proposed design solutions. Their proposed programmes for low-income people during Phase I (2008-2013) do not merit technical comments for being grossly tentative. For example, density in two low-income housing proposals of 50 and 5 acre of land are 300 and 1050 units per acre respectively. Alarming absences observed in the Annexure in informing us are, first, how selected precedence considers the issue of sustainability, in particular, in the use of scarce land, energy and natural amenities. Second, how these examples become responsive to the dwellers way of life by ensuring residential satisfaction. They have left us deeply concerned about the impending catastrophe of design determinism's featuring our future lives in Dhaka.

Now I would reflect on the noted inadequacies and inconsistencies of the product fetishism.

The proposed 'vision of housing for all by 2025' would initiate a 'social transformation' through 'spatial restructuring' of the Dhaka city by delivering 4.45 million dwelling units. Dhaka would surely be a different city than what we know of it today, socially and physically. One can suspect hidden in this vision is the beginning of a paradigm shift in urban policy. The key feature of the existing urban policy has been the 'developmentalist intervention' in the context of rampant informality and illegality; it identifies, enumerates and surveys a specific 'population' group as poor or slum dwellers to offer services and assistances that they otherwise would not be able to claim legally. While the upcoming policy would feature a 'modernist intervention' in the formal and legal context of it's served 'citizens' classified on income groups. The proposal aims to transform the urban poor population into low-income citizens through their access to formal and legal housing. Being citizen, the poor would pursue their rightful claim on resources as long as they can afford buying in the market.

So far so good toward a Dhaka without slums. The aim is laudable; however, citizenship is but access to housing alone. What about poor citizens' access to employment, education, health, and importantly, political participation? At present, no one gets any clue from the proposal regarding how these needs of the urban poor would be met. Given the neo-liberal policy regime pursued around developing countries, state subsidy in the utility and service sector would be a thing in the past.

Housing is not an end in one's access to a given product but a means to achieve true citizenship to live a life that people value. To situate the significance of housing process today, beyond its delivered physical product, we can quote from Arjun Appadurai's Deep Democracy: “Housing can be argued to be the single most critical site of this city's [Mumbai] politics of citizenship”. This view becomes clear in Dhaka if we ask how does the proposal hope to trigger a reversal of the existing exclusion of the poor from all decision making process? Where had the evicted poor from Korail slum stood in voicing their opinion in the initial allocation of land for rehabilitation in Korail, or later, in its cancellation? Despite all rhetoric, the evicted poor have had actually disempowered, i.e. left to ponder without having any voice to negotiate their claims from the authority. A process driven housing would have never ignored the poor. This proposal with its product bias erodes completely what Partha Chatterjee has perceptively called “The Politics of the Governed”. Amidst informality and illegality in the cities in developing countries, the governed populationthe poorhave their own ways of coming into terms with the governing regime: the Poor's real politic of survival.

The offered 'vision of housing for all by 2025' envisions a different Dhaka that has already started unfolding its scheme of restructuring city space and power-relations. The Dhaka city has lately been offering a spatial premise for productions, consumptions and transactions within a global network of cities. Micheal Hardth and Antonio Negri take that as outcome of a new 'Empire'. New business/corporate elite has evolved amidst citizens and discrete population groups in Dhaka by their gainful integration in the global as much as in national economy. An effective and efficiently functioning city as well as disciplined labour force is central to their business, trade and commerce. Rapid modernization of Dhaka's infrastructure and transportation are first (billion dollars) business themselves in addition to good for other businesses by their value-added contribution to increasing productivity. Opposite side of the vision for housing is actually a vision for good business, initially in the construction sector then beyond for the reproduction of labour in other sectors. It is no surprise that the elite citizens, read businessmen, their benefactors and corporate agglomerates, have drawn attention in the policy making level; in national politics too. Their powerful presence is hard to ignore. One author in the seminar had actually gone to justify the proposal's giving of ten katha lands for the rich businessmen; otherwise they would leave the country to settle abroad. Let us now explain the proposal's sense of unjust benevolence against equity.

In offering a vision for housing, we would now chart the ground that makes an academic different from a politician or a businessman. A politician ought to resolve a housing problem, i.e. shortage of dwelling units, among probable alternatives in the public interest. If knowing the causes of a problem is a precondition for its solution then I believe a politician in our country does not want to know the deep rooted cause of the problem unless its revelation offers him the opportunity to blame the past, deeds of the political opponent in particular. Politician is usually interested in quick-fix, and importantly, to show to the public the results of actions within his/her/their tenure. The urgency to show the results would be more if the problem is the politician's own making. The path followed by a businessman to resolve the housing problem, on the contrary, is driven by the opportunity of making profit. A businessman ensures his profit first, the greater the better. Knowing the problem he wishes to encounter is welcome as long as it offers, again, opportunity for making profit. Profit by investments in housing surely does not have to be a bad word after all; but the question is profiting at what cost, at whose expanse?

An academic's path, ideally speaking, differs from a politician or a businessman as he is alleged to have worked from a neutral space with no interest in the outcome other than the public wellbeing. An academic's output can and should be of pragmatic values in guiding policies and programmes rather than remain an inert academic exercise. Unfortunately, the presented proposal is but an academic's vision; it is devoid of either academic content or pragmatic value.

The presented 'vision for a housing programme' dwells in product fetishism; it stays away from grasping what 'housing' or urban living would be like toward 2025 and beyond: how to manage a habitat for so many people in so less land. Proposal's product fetishism makes ground for the commodification of housing; a rather biased commodification, solely for the owner-occupiers with no consideration for the middle-income renters. One does not necessarily become a revolutionary either to offer a critique or rethink a vision for housing. However, one's contemplating upon a vision for housing requires going beyond naïve positivist linear reasoning. One's claim to offer a vision for housing has to build upon, first, an understanding of the making of the government's inability to provide affordable land and housing. Second, a revelation of the causes of the poorest section's continued living without 'adequate shelter'.

The proposal has been a classic example of the native 'self's' portrayal of what the 'other' should have. This portrayal, soaked in unmasked parochialism, originates from the narrow, uncritical positivist urban studies a premise that delivers commissioned surveys more comfortably than original studies. We have a vision for future in hand that is ignorant of its past, especially, the housing history of Dhaka.

This history would portray the privileged position the native self in Dhaka holds as an outcome due to, first, the imported modernity's separation from the traditional by identifying modern housing different and superior than popular housing. Second, the ways power and wealth have accumulated asymmetrically among the rich elite had contributed to their manipulation of the institutional means in their favoured access to formal housing. Third, increasing income-asset-opportunity inequality in Dhaka has marginalized the poor in claiming their access to housing.

Above reflection will now be wrapped up. Land and people are the two most essential ingredients of any city, giving spatiality and life to the city. Housing has always been the crucial arena where land and people infused to give meaning to the city, and importantly, not by avoiding competing interests. The point is that housing in a city has always been a contested arena: who wins and who loses in one's access to housing remains a question to reckon with, to discuss and debate in the public realm. Nagar Unnayan Committee should certainly think about how best to infuse people and land, along with many different aspects, in the comprehensive development of housing for Dhaka. It wouldn't be unfair to suggest that the Nagar Unnayan Committee should try its best not to be autonomous in thinking but work in close relationship to the existing statutory and institutional tools and mechanisms.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments