Power dressing: Exhibition at the Met inspired by superheroes

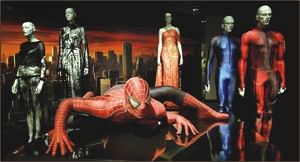

The Spider-Man display includes Tobey Maguire's costume from Spider-Man 3 and cobweb knit, web-embroidered ensembles

Superheroes exist for many reasons. Certainly in our time they exist to sell movie tickets and plastic action figures. But superheroes, those crusading men and women in tights, allow us to believe that in a cape or magical second skin we can do the impossible. We can transform ourselves.

Fashion thrives on the same expectation: Buy this hot dress or pair of Jimmy Choos, and see if you don't feel curiously invincible at the next party. To an extent all superheroes, like some of the most flamboyant creatures in fashion, are playing a role inadvertently thrust on them by circumstance, their true identities and physical shortcomings concealed.

The ideas that dominate fashion -- identity, performance, gender, body shapes, sexuality, logos and the quest for state-of-the-art materials -- pretty well describe the world of the superhero.

These two forces are brought together in “Superheroes: Fashion and Fantasy,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art's playful look at comic book costumes and their influence on radical haute couture as well as high-tech sportswear. Organised by Andrew Bolton, curator of the Met's Costume Institute, the exhibition is a departure from the museum's lavish historical surveys. This is the lighter, more fantastical side of fashion, an industry that loves to talk about the genius of Balenciaga while clamouring to dress the body of Beyoncé. Yet inevitably fashion is pioneered by the young, by their daydreams and obsessions, and this exhibition may open one's eyes to new modes of style as surely as a fur-lined teacup or a slashed punk T-shirt depicting the British queen.

The notion of experiment is embodied in the design, which was done by Nathan Crowley, the production designer on two Batman films and the exhibition's creative consultant. The 60 outfits, many from movies, are displayed in a sleek, white, brightly illuminated space that suggests a laboratory. All that clinical whiteness, along with three sections of mirrors arranged to create an endless reflection, helps to set off the extreme materials of the costumes and the vivid Gotham backdrops.

Superheroes emerged in the late 1930s, the hinge years between the misery of the Great Depression and the start of World War II.

Wonder Woman, created by William Moulton Marston, first appeared against a patriotic Washington skyline in January 1942. The drawn version -- unlike Lynda Carter's television character with her 22-inch waist and ample bust -- looks wholesome and cute in her flirty star-patterned skirt and bustier. Clark Kent, when trouble loomed, slipped out of his street clothes and into Superman's sleek, empowering unitard. But the 1930s also marked the introduction of a streamlined modernity in interior design, automobiles and the fashion of couturiers like Madeleine Vionnet, whose dresses flowed like liquid over the skin. For contemporary designers like Jean Paul Gaultier, who did a printed version of the unitard in 1995, the attraction of a comic hero's “second skin” may be that it looks modern.

Quite a few of the fashion interpretations of superhero costumes here are fairly literal and do little to expand our knowledge of either form of expression. Bernhard Willhelm's 2006 Superman-inspired dress features an S logo that appears to be dematerialising in drips of red, while a Moschino three-piece suit from 2006 sports a T-shirt emblazoned with a red M. But beyond commenting on the proliferation of logos and branding, what do these garments tell us?

In the Spider-Man display, which includes Tobey Maguire's costume from “Spider-Man 3,” there are a number of cobweb knit and web-embroidered ensembles. Some of these show finesse and sly humour, like a 1990 Giorgio Armani gown traced in silk threads and crystal beads. But you can't really know if this design springs from the natural world or a comic book, and you are left simply to marvel at its creepy beauty -- which may be enough.

It's camp. But when these pieces were first shown on a Paris runway they were unfairly dismissed as crass, and Mugler's motives were questioned. There was very little attempt to understand the themes of violence and eroticism conveyed in the style. Certainly these ideas are the basis for a lot of contemporary art and literature. You have to wonder if the reason Mugler didn't receive serious consideration is that he was a dressmaker.

Designers liberate themselves from the banal just as superheroes do. They do remarkable things with materials and craft. Dolce & Gabbana's corseted minidress from 2007 looks as if it were moulded from Tiffany silver. It is actually made of leather. Although it would have been nice to see more clothing examples from the 1960s and '70s, and more abstract takes on transformation -- where is Comme des Garçons, the avant-garde label of Rei Kawakubo? -- Bolton intelligibly connects these two distinct worlds.

And while it's surprising that only two American designers are included in the exhibition -- Rick Owens and As Four -- it is also understandable. Superheroes are largely an American invention, and designers here are probably too close to Catwoman and the Flash to be inspired in a new or funny way. Their fantasies involve England or Rome, not Krypton.

Source: The New York Times

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments