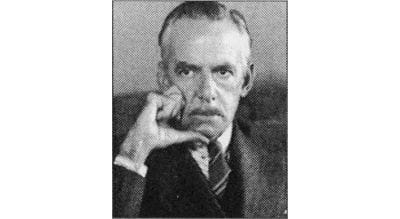

Eugene O'Neill and American drama

November 27 marked the 59th death anniversary of America's pre-eminent playwright Eugene O'Neill. O'Neill has long been a fixture of the modern American dramatic literature curriculum in colleges and universities worldwide. His plays are considered exceptional not only in plumbing the depths of human emotion, but also in presenting a disconcerting image of American cultural life. O'Neill wrote fifty one plays. He was awarded four Pulitzers and a Nobel Prize in literature in 1936the only playwright who has achieved such a feat so far in America. As a dramatist he was highly experimental in technique, and his themes generally involved lust for power, body, land and oil; reinventing pagan depths in American complexities, racial and class problems; and his family.

Most of O'Neill's plays depict some disturbing struggles in the raced, gendered, and classed power structures. His characters are governed by the desire to own almost everything and anything, which is a very characteristically capitalistic, and hence American trait. The ownership would be revealed, in the manners of psychological stripteases, through conflicts between a kleptocratic autocrat and his citizens as seen in The Emperor Jones; between black and white as seen in All God's Chillun Got Wings; between working and capitalist classes as seen in The Hairy Ape; between material possession (land, oil) and dispossession as seen in Desire under the Elms and Ile; between masked and unmasked articulations of the ever changing self as in The Great God Brown, only to name a few. O'Neill became a maestro in depicting on stage how desires turn simply into deceits that take away the truth of life in two of his later autobiographical plays: Long Day's Journey into Night and The Iceman Cometh.

Long Day's Journey into Night is a rags-to-riches story of an Irish migrant, James Tyrone, who sacrifices art to avarice to accumulate wealth. Arriving in America as a kid right after potato famine struck Ireland, it does not take long for a streetwise Tyrone to learn that money is the benchmark for human excellence. Although he reaches the pinnacle of the American dream of success, drugs, alcohol, and disease now run havoc in Tyrone's family for which money can't be a balm. The play ends with all its members appearing as haunted figures on stage trying to build a smokescreen with illusion through drug and booze. The plotline is based on the playwright's family, and hence the characters are replicas of O'Neills: his cheapskate, matinee idol father, drug addict mother, wastrel elder brother, and O'Neill himself the tubercular son. While O'Neill just cherry-picked a day's incident from his life for the play, eventually it became a telescoped event in the life of Americans where Tyrones are Everyman in a country of immigrants. In the saloon play The Iceman Cometh, the playwright again revisits his memory lane. It involves some down-and-out friends who have run out of luck in life. Wine flows free in the bar room of the motel, and everyone here is either talking rubbish or fighting among themselves. They are all waiting for the arrival of the charismatic salesman Hickey who visits this place once in a year on the birthday of the bar owner, Larry.

O'Neill here presents the American cultural-political archetype of the traveling salesman in the post-World War II era, exactly on the eve of America's emergence as the richest and most powerful country on the planet. A uniquely American mythic figure, Hickey's portrait presages two of America's most famous salespersons seen on stage during the 1940s: flinty Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire and awful Willy Loman in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. Hickey, however, is the first American sales agent of the capitalistic era who leaves a stage-legacy for Stanley and Willy by never apprising the audience of his selling product. This particular cult of salesmanship, germinated as a derivative of the American brand of capitalism, which O'Neill uses as an abstraction and Miller and Williams sincerely follow him, perhaps means to carry a point of view. All three salesman-protagonists are actually selling the product called death, traveling and covering distances and thus conforming to an American worldview that later will suit Anthony Giddens' famous explanation of globalization in the latter's The Consequences of Modernity. Hickey sells it to his wife, one bar member, and finally to himself; Stanley to Blanche, and to some extent, Mitch; and Willy to himself and to his sons.

Edward Albee wrote a moving foreword to O'Neill's long lost play Exorcism, published for the first time in February 2012 by Yale University. Albee, whose Zoo Story was the booster rocket that launched American absurdist genre into the world literature orbit in 1959, was branded over the last half of the twentieth century as the flag bearer of Beckett and Pinter in America. Albee broke the fifty-year silence by binning such a long-held scholarly premise when he declared that it was not any European dramatist but his compatriot O'Neill whose plays, like The Iceman Cometh, served as the launching pad for his entire canon of absurdist drama.

By any objective criterion, therefore, Eugene O'Neill stands as the virtuoso dramatist that the American theatre has ever produced. Broadway success, originality, international acclaim, foundational contributions and theatrical innovations for which he is creditedall attest to his pre-eminence as America's leading playwright. Williams, Miller, and Albee followed him; Sam Shepard, David Mamet, August Wilson, and Tony Kushner acknowledged their profound debt to him. Tennessee Williams once remarked, “O'Neill gave birth to American theatre and died for it.†The appeal of O'Neill is universal simply because like great writers, he reveals the truth about human conditions, shows understanding of the human individual that rises above time and place. That is what makes the playwright very much contemporary to us.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments