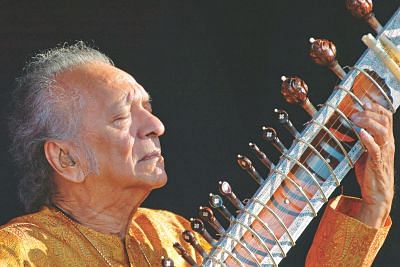

<i>The Sitar falls silent</i>

With him goes a coruscating era in Hindustani classical music. For Pandit Ravi Shankar embodied an entire genre of melody, one that he not only recommended to the world outside India but also worked assiduously in giving it the deft touch it needed, his own. It was the sitar through which he spoke. And he spoke not through a laboured demonstration of determination to master the art, but through a spontaneous display of emotions that music often brings up in the one who lives and breathes it.

Ravi Shankar was born to create music. There was about the making of melody in Ravi Shankar something that emerged from within, something in the nature of cool water bathing the arid stones of mountains and soaking in spring warmth the fallow earth in the foothills of the mountains.

Ravi Shankar was spring personified, in that metaphorical sense of the meaning. In the literal, he was the child of spring, for it was on an April day that the earth welcomed him into its bosom. And then began a long life that would only be a long train of spring songs that he would create for the world to hear. Branching out into the world beyond India with elder brother Uday Shankar at the tender age of ten, it was the future that the future maestro deciphered in the capitals of the globe. And that future was not to be had in dancing, a vocation Ravi Shankar had set for himself. He was wise enough to understand that the future lay in a re-creation of the grandeur of the Indian musical past. Indeed, it was Tansen to whom everyone wished to return; it was heritage flowing from the sitar and the tabla that held everyone in raptures. Ravi Shankar knew then that the sitar was his calling. He went, sitar in hand, to the courtyard of the great man of classical music, none other than Ustad Allauddin Khan. Shankar was eighteen. Khan discerned the future in the youth.

After that there was no stopping the exuberance of the young man. Life was not all about music, but Ravi Shankar persuaded himself into believing that music gave life the notes it needed to give meaning to those who inhabited the world. In time, Shankar would team up with Satyajit Ray to score the music that would turn the latter's Apu Trilogy into a household image around the world. For Shankar as for Ray, perfection was all. Flawed music was no music. That Indian classical music stretched back in time, that it was a harkening back to ages lost in the setting of the sun, was the message Ravi Shankar sought to convey in his odyssey across America and Europe and the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s. To the West, Ravi Shankar's music was a rediscovery of India, of an ancient civilization throbbing with life in modernity. There was the cosmopolitan in Shankar even as the essence of his melody remained pure Hindustani. He had western music makers and aficionados mesmerized with the way his fingers strummed the sitar. They sought to draw the light and the energy, for their compositions, which shone through in Shankar. Andre Previn and Philip Glass and Yehudi Menuhin were among those proud to be in Shankar's company; and Shankar was cheered by the prospect of his creativity casting its glow in lands that remembered Mozart and Wagner and Haydn. Ravi Shankar strummed for Gandhi, the movie. In the late 1980s, he would send people into spasms of ecstasy with the dance drama Ghyanasham.

With George Harrison, he of the Beatles, Ravi Shankar was a soul brother. Transfixed by Shankar's sitar, the playing of it, Harrison spent as many as six weeks studying the sitar, its moods and its many nuances, under Shankar. In August 1971, the two men teamed up again --- to inform the world of the brutalities being perpetrated on the people of Bangladesh by the Pakistan occupation army. Harrison sang, Shankar played the table and everyone at New York's Madison Garden and beyond wept. If music could draw attention to a political cause, Shankar and Harrison did the job terrifically with the Concert for Bangladesh. And Bangladesh has not forgotten.

It is to this great voice of music, our very own Pandit Ravi Shankar, that we pay homage today. He was the subcontinent's Robindro Shaunkar Chowdhury. In another day and age, he would be sharing the world of the ancient gods --- Greek or Roman or of Indian mythology --- rocking paradise gently with the leafy strains of the sitar, making the stars go tipsy in the soft cadences of song.

The sitar has fallen silent. Spring is gone and winter winds scream through the bare trees.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments