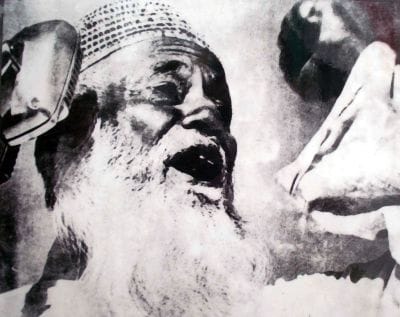

Maulana Bhasani: A leader close to people's hearts

Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani

It was on November 17, 1976, that the Doyen of Bengal, Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani, set sail towards the Great Unknown and reached the shore from which no traveller returns.

Many said that his death meant the end of an epoch. It did no doubt mark the end of an era of charismatic leadership, especially to those with longer memories of the exhilarations and ecstasies and desperations of our long and gruelling struggle for freedom. But Bhasani was no mere charisma. In the political firmament of this subcontinent studded with so many supernovas, there perhaps has never been a more humane man -- fallible, prone when he was younger to gusts of passion, albeit with a supreme capacity for recovering his balance.

We shall never see the likes of him again.

A study of his career reads like a romance. He was a man daring and adventurous, reckless of consequences, and yet intensely practical. He was many-sided, complex, full of conflicting enthusiasms and burdened by many sorrows. Yet there has seldom been a public figure who was more open with his problems and his thoughts, in private letters and public print, in speeches and talks with friends and disciples. A giant among men, he was always above all pettiness -- the envy and jealousy and prejudices and irritations of ordinary men. Dedicated to a noble cause as he always was, his was always a selfless life -- free from all narrowness, truthful in thought, fearless in action, meek as a lamb, but a lion in spirit.

His remarkable ability to combine political flexibility with an overriding sense of moral purpose helped liberate Bangladesh. Yet he knew that political independence was a means and not an end, and that only through dedicated efforts, education and respect for the rights and opinions of others could a people become truly free. Unlike the leaders of many other political movements, he always stressed that the means were far more important than the ends. He stressed over and over again that when the means were right the end was bound to be right. But even when the end was good or excellent and the means were vitiated, the ends too got vitiated.

The dynamic nobility of his character made him almost the creator of a free democratic society in this part of the subcontinent. "He saw life," in the words of Carter, "as a seamless whole in which every action, every experience, is drenched in meaning."

But what one admired and loved was not only the forceful nobility in him, not only the indomitable courage and the supreme conviction of this giant among men, but also his great sense of belonging, not only to his own country but to the whole world, his intellectual affluence, his air of remoteness, his affection of excellence, his ease of bearing amidst the greatest and the lowliest, his absolute confidence in his own generous instincts, his sincere solicitude for the neglected and the obscure, his unshakable firm faith in Islam.

He knew his country and people well and he was always certain within himself of what was good for Bangladesh. His position in the social and political arena of the then East Pakistan and sovereign Bangladesh was always natural, never official. Presidents and prime ministers came and went, but he gave his country the leadership which was somewhat like Mahatma Gandhi's in India -- though in many ways the thoughts and ideas of these two giants were very different and, in the words once used by George Bernard Shaw: "Very unlike a plug of tobacco which can be passed on from one hand to another."

He disdained to acknowledge his limitations as a human being and like a true mujahid could so often take risks with his own life. He never hesitated to rebuke and bring to book even great and powerful men in public and sometimes right on their faces, but he always had a delicate courtesy and, in human relations, a subtle sense of what may be due to the other men, friends and foes alike.

He had been a Titan of sorts, a leader, a true leader, who shaped the modern history of his country from the earliest days of colonial rule through liberation. But he was unique as a public figure in having no public facade. He never had that falsifying consciousness of how he might be appearing to others that makes so many politicians stiff, or relaxed in bogusness. With him the world was never painted in harshly contrasting blacks and whites but in subtle intermediate shades. His was a life dedicated to the pursuit of truth and excellence.

As the ceremonies are observed with solemnity, dignity and poignancy, the people will remember, and show their deep appreciation of the great love that the leader bore them. The people's capacity for repayment will seem to them to be as limited as Maulana felt his own to be. Yet this he would not have accepted.

Bhasani is no more, his mortal remains are no more. The daring and indomitable Maulana is part of history today -- he has "shaded himself," in the words of Omar Khayyam, "with yesterday's seven thousand years." But his ideals are there, his achievements are there, his spirit lives with us -- "the light is extinguished but the beacon remains." His mantle has fallen today not on any particular person but on the people of Bangladesh whose grief is great but whose tasks are greater.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments