<i>Silence of the storyteller</i>

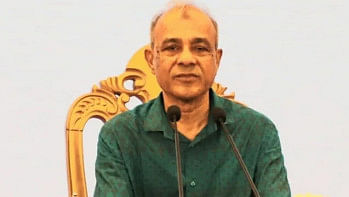

At first sight, Humayun Ahmed came close to resembling an academic. Bespectacled, speaking in a low voice, he quite belied the truth of his being a writer. That image of the academic became him. After all, he had once been a teacher at Dhaka University. The subject he taught was chemistry. He could have stayed there, could have climbed the ladder to even higher academic perches. But then came Nondito Noroke, in the defining, often distracting 1970s. It changed his life as it changed the thought processes of millions in Bangladesh. Suddenly there was a new man with a different take on fiction. Suddenly, the crowd of readers of Bengali fiction widened.

The storyteller will tell stories no more. The final chapter of the exciting, intense tale of his life came, not through words or literary nuances, but through the silence which descended on his life in distant New York last night. The news of Humayun Ahmed’s passing, snaking its way into the nooks and crevices of the collective Bangladeshi soul in the depths of profound darkness, was jarring. It shook us up, even those who had not read Humayun Ahmed. It raised that painful, age-old question: did the writer know of the approaching end? He was here, back home, recently before travelling back to New York for a continuation of his treatment for cancer. We deluded ourselves into believing that he had overcome the forces of death, that he would soon be back among us in revitalized form. But perhaps only he knew that the twilight was at hand? Perhaps he understood the need for a final experiencing of the air and aroma of his land of birth before the music of life drew to a close?

Yes, Humayun Ahmed was a powerful writer, one whose fiction sold endlessly. The young and the middle-aged never ceased talking about some book or the other by him. Prolific writing all too often mars quality in a writer. In Humayun Ahmed, quality remained a matter of consistency. His novels were lapped up by fanatical tribes of readers. His television dramas gave a new, sharper edge to middle class sentiments. Citizens across the spectrum spotted in his characters, both in the novels and in the plays, their own selves, warts and all. The pathos, the ambition, the ego, the secret desires which on a quotidian basis assail us or keep us going, as the case may be, all gleamed in his works. In Ei Shob Din Raatri, in Oyomoy, indeed everywhere, Humayun Ahmed spoke to us. Or we were the characters portrayed in his tales, transported from the banality of our world into images where the banality acquired a special quality of its own. Reflect on Baker Bhai. He was our own local goon-cum-hero. We would not let him die. Neither would we put up with his mischief.

That was the creative imagination in Humayun Ahmed. Its roots lay in our social realism, of which the writer was only too aware. His mother and his siblings walked through the prism of moving time in the shadows of a deathly past. His father was done to death by an army of genocide in our long-ago war for freedom. That pain was a constant. In Humayun Ahmed, then, lurked the tale which beats in every Bengali’s heart. There was darkness before the dawn. That is the tale. But even dawn sometimes comes draped in the tears of the past. So it was with Humayun Ahmed, with his characters.

He was our first writer who crossed the threshold to celebrity status. Stardom was his to savour. Much as you argue over his place in the history of Bengali literature, much as you might take issue with his approach to things imaginative, to his interpretations of history (as in Deyal), you cannot but agree that he touched lives in a way no other spinner of words in this land has done before. He looms over you as a formidable presence.

And now comes the loud silence, one that mortality will not allow to be lifted. Humayun Ahmed has transited to a world beyond ours.

Suddenly, in searing manner, our world is changed. Our weekend good cheer has given way to the question: what do we do, now that the master storyteller is gone?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments