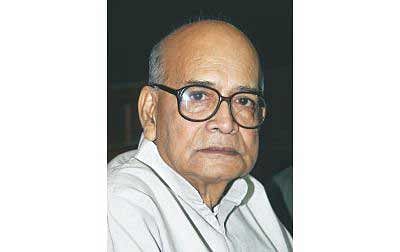

Muzaffer Ahmed: A recollection

It was late 1973. I had just returned from abroad after a study leave and was back at the Planning Commission. Muzaffer Ahmed was the chief of the industries division, one of the major segments into which the Commission was then divided. I had joined another division, at a more junior post than Professor Ahmed's. We had offices in the same building of the Secretariat. One afternoon, at the end of a long working day, he offered me a lift in his old Volkswagen beetle.

The car had no ignition key. Those were the days of lawlessness, muggings, hijackings, car break-ins and much more. There was a colleague of mine who had a sheet of transparent plastic for windshield, the original having been stolen. Muzaffer Ahmed's car had perhaps been vandalised, part of the dashboard gone, wirings exposed. The ignition was achieved instead by a touch-and-let-go between the ends of two loose wires. The car sped through the chaotic streets of Dacca. It soon stalled. Ignition again. The car was once more on its way. It stalled again, and had to be given renewed ignition. It was after several of stalls and starts that he dropped me off where I had wanted him to.

An image of a distant past. A little hazy, it has stuck with me.

We were not close friends, but we had known each other for many years. Muzaffer Ahmed was a year junior to me as a student at Dacca University in the early 1950s. Our contact in the post-university days had been tenuous. Still, every time we met there was a mutual renewal of an intellectual acquaintance that had been maturing over the years. As economists we did not always see eye to eye with each other. He was a strong supporter of public enterprise and perhaps more than a little disdainful of liberal trade. I came to view the former with suspicion and the latter as something well worth exploiting for economic growth.

Neither did he seem happy to see the likes of me living in foreign land rather than contributing to nation-building. He could well have echoed Dr. Mazharul Haq, the wit, and teacher to both of us at Dacca University: "I am not that kind of a patriot who would lie abroad." It was, however, only when we had both been abroad that we had the kind of opportunity to converse that we never had in Dacca.

I lived in Manhattan. One day I got a surprise call from Muzaffer Ahmed. He was in Boston on an academic stint and was calling to find out if he and his family could come down to New York and stay with us for a couple of days. I said he certainly could.

A good deal of the few days they stayed with us was spent by them sightseeing. Muzaffer Ahmad and his wife spent a day shopping for books, exploring miles of shelves at the Strand bookstore situated not far from our neighbourhood, while we babysat their two children. Muzaffer Ahmed was a voracious reader. Back at our apartment, between meals and conversation, he always found time to perform his five daily prayers. He also fasted in Ramadan, even on the very long summer days in Boston. To him faith and intellect sat in perfect harmony with each other.

That was almost three decades ago. We lost touch with each other. But I was keenly aware of his work beyond the confines of economics. Corruption and environmental degradation had been eating into the heart of the society. He plunged into these issues and played a pioneering role in the fight on both fronts. To these was added the issue of good governance and the role of the civil society in it. They presented a huge tangle of wires, many of them dangerous, some crossed. And there was no magic ignition key. Still, he set the vehicle going, while flak kept coming in. Perhaps this was his greatest achievement.

Back in 2010, I was celebrating the launching of a book of mine in Dhaka. Unsure of his schedule and inclination, I failed to invite him to the launch. He turned up, having been briefed by a mutual friend. He sat through most of the discussions on the book from the dais where I sat. Towards the end, he got up and slowly made for the door, shaking me by the hand as he left, a faint goodbye on his breath. I never saw him again.

I wish I could tell him how sorry I was for the belatedness of this wholly inadequate tribute.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments