Buena Vista Anti-Social Club: Inside Cuba's hidden metal scene

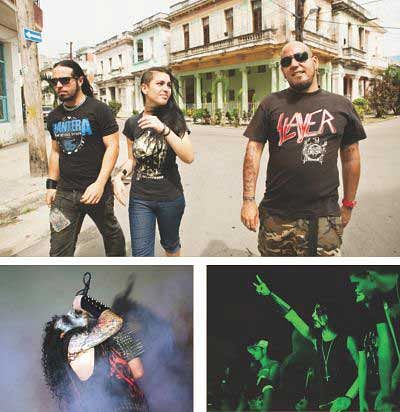

Clockwise from top: Cuban band Escape strolls through Old Havana. Fans at 666 Fest in March 2012. Ancestor lead singer Viktor Hyde.

As the world gets smaller and more connected every day, Cuba remains isolated and repressed, mired in poverty and outdated technology. It's no wonder that the country is responsible for some of the angriest, most extreme metal on Earth.

The park at the corner of 23rd Avenue and G Street in the Vedado section of Havana isn't much to look at by the standards of fading, crumbling glory that prevail in Cuba's capital city. In fact, it's less a park than a median that bisects the wide expanse of G Street: some patches of green grass, a few paved walkways, and maybe a half-dozen benches, all within about 100 square feet.

At 1 a.m. on a warm, windy Friday night in mid-March, the park is a sea of long, dark hair and black concert T-shirts-- Slayer, Bathory, Gorgoroth, Megadeth. Led by Amed "Helheim" Olivares, frontman for Abaddon, a young band that, hours earlier, had played a relentless, assaultive 45-minute set at an Art Deco cinema a few blocks away during the first night of the third annual 666 Fest, a weekend-long celebration of Cuban black metal. After wiping the corpse paint from his face and the black, upside-down cross from his arm, and stowing the nail-studded armband he wore onstage.

"For metal in Cuba, you have to see G Street," he says.

Metalheads have been hanging out on this unremarkable corner most weekend nights since the mid-'90s. Nobody seems to know why they chose this location, but whiling away the nighttime hours outside, hanging with like-minded comrades, is common in Havana.

Almost all of the hundred or so gathered came from the festival, and while they look somewhat intimidating from afar, it's just an illusion. People here are friendly, and with the exception of one heavily inebriated man who keeps dropping his shorts and exposing himself, well-behaved.

The 666 Fest isn't Cuba's biggest metal festival-- the show drew approximately 200 people. In a country ruled for more than 50 years by Communist regime, heavy metal has taken hold over the past two decades in a major way. While its audience is dwarfed by that for salsa or reggaeton, its stylistic leanings and brash, antisocial attitude are eye-opening. Metal here is almost uniformly deafening, punishing, and brutally aggressive. As Michel Hernández, frontman for a popular thrash-metal outfit called Chlover, puts it, "We don't listen to Bon Jovi here."

Joel Kaos, one of the festival's organizers, is a surprisingly cheery guy who plays bass in Ancestor, an anarchic, thunderous black-metal band which is headlining Saturday's show. "You need extreme music to match your extreme life," he says, drawing a direct cause and effect. "You find harder metal in countries that are more oppressed. We have something to scream about."

That this scene is blossoming seems to indicate an opening up of what has long been the Western Hemisphere's most repressive society. But like everything in Cuba, the reality is more complicated: A combination of onerous travel restrictions and dire economic conditions means that for most Cubans-- and most Cuban metal bands-- it's extremely difficult, if not impossible, to ever leave the island.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments