ITLOS judgment : An analysis

Immediately after the delivery of the judgment by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS/Tribunal) in the Bangladesh/Myanmar maritime delimitation case on March 14, there were claims by AL of a complete victory over Myanmar. These claims were complemented by casting blame on BNP for its failure to have the maritime boundary dispute resolved. BNP, on the other hand, has taken the position that the government's campaign over winning the case is a trick to deceive people and urged the government not to confuse people by telling lies.

The claims of both political parties are far from accurate. Bangladesh won on some points in the case, and lost in others. Likewise, Myanmar won on some points and lost in others. The outcome, thus, is one where neither party had a complete victory or a total defeat.

ITLOS delimited maritime boundary between Bangladesh and Myanmar in three maritime zones, which are, the territorial sea, the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and the continental shelf.

Relevant provisions of UNCLOS

The law that is applied in respect of maritime delimitation is set out in the United Nations Convention on the Law of Sea of 1982 (UNCLOS). According to Articles 3, 4 and 5 of UNCLOS, territorial sea extends to 12 nautical miles (nm) from the low-water line along the coast, referred to as the baseline. The coastal state has full sovereign rights over the territorial sea, similar to rights that a state has over its land territory.

According to Articles 55 and 57, exclusive economic zone is an area beyond and adjacent to the territorial sea, which extends to 200 nm from the baseline. In the EEZ, coastal state has sovereign rights for exploring, exploiting, conserving and managing natural resources.

According to Article 76, continental shelf is the seabed and the subsoil that extends from the coast throughout the natural prolongation of the land territory. The outer limit of the continental shelf is either the outer edge of the continental margin, or to a distance of 200 nm from the baseline where the outer edge does not extend up to that distance. Thus, while EEZ extends up to a maximum of 200 nm, the continental shelf can extend much further, depending on the location of the outer edge of the continental margin. According to Article 77, coastal state has sovereign rights of exploring and exploiting natural resources of the continental shelf. These rights extend to natural resources of the seabed and the subsoil and, unlike EEZ, do not extend to the waters or to the air space above the waters.

Under the applicable provisions of UNCLOS, delimitation of the territorial sea, where the coasts of two states are adjacent to each other (like the coasts of Bangladesh and Myanmar), must be made on the basis of the equidistance principle while delimitation of the EEZ and the continental shelf must be made with the aim to achieve an "equitable solution." Equidistance line being the median line, every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points on the baselines of the adjacent states, its application in delimiting the territorial sea does not pose any problems. However, equity being an abstract notion, in delimiting the EEZ and the continental shelf, this abstract notion needs to be given a more concrete meaning.

Case law and state practice

Over many years, the International Court of Justice and a number of international arbitration tribunals, which adjudicated disputes on maritime boundary, have sought to provide a concrete understanding to the notion of "equity" in delimiting the EEZ and the continental shelf. According to these decisions and practice, the delimitation process should begin by first establishing a provisional equidistance line, which may be adjusted in the light of "relevant circumstances" for achieving an equitable solution.

In the Bangladesh/Myanmar case, ITLOS strictly followed the UNCLOS and the aforesaid case law and state practice. Thus, ITLOS delimited the territorial sea boundary by applying the equidistance principle and the EEZ and the continental shelf boundary by applying "equidistance/relevant circumstances" principle.

Delimitation of the territorial sea

Bangladesh argued that the Agreed Minutes of discussions between the parties in 1974 and 2008 constituted an agreement regarding territorial sea boundary, while Myanmar denied any such agreement. ITLOS decided that those Minutes did not constitute an agreement and accordingly proceeded to delimit the territorial sea. In the end, by 21 votes to 1, an equidistance line from the base points of Bangladesh and Myanmar was drawn by ITLOS as the territorial sea boundary. Likewise, an equidistance line formed the boundary between St. Martin's Island and Myanmar, but where the territorial sea of the St. Martin's Island no longer overlapped with the territorial sea of Myanmar, Bangladesh was allowed to extend the territorial sea of the island to 12 nm.

Delimitation of the EEZ and the continental shelf

With respect to the EEZ and the continental shelf, Bangladesh argued that "equidistance" was not an appropriate method, as it did not produce an equitable result. Bangladesh argued that in view of the configuration and concavity of its coast, ITLOS should apply the "angle-bisector method" in delimiting the EEZ and the continental shelf. "Angle-bisector method" is an alternative to the equidistance method and is used much less frequently than the equidistance method. Myanmar, on the other hand, opted for the "equidistance/relevant circumstances" method.

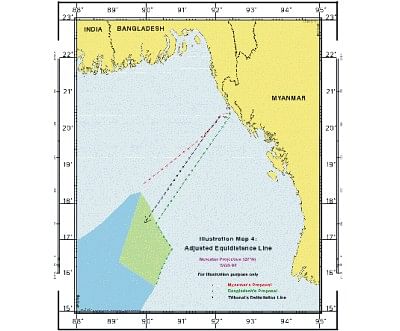

ITLOS decided in favour of the "equidistance/relevant circumstances" method and accordingly established a provisional equidistance line and then adjusted that line taking into account the "relevant circumstances." The first step in drawing an equidistance line is selection of base points from which the line is to be drawn. Since we opposed the equidistance method, we did not identify any base points. ITLOS, therefore, relied on the five base points identified by Myanmar and selected a sixth base point itself. A provisional equidistance line was drawn relying on those six base points.

Having drawn the provisional equidistance line, the Tribunal considered the relevant circumstances. In this context, Bangladesh argued that there were three main relevant circumstances, which should be taken into account. These were the concave shape of Bangladesh's coastline, the St Martin's Island and the "Bengal depositional system," which connected the landmass of Bangladesh with the seafloor of the Bay of Bengal. Myanmar, however, argued that there did not exist any "relevant circumstance" that might lead to an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line.

The Tribunal accepted the concavity of the coast as the only "relevant circumstance" and declined to find the St. Martin's Island or the depositional system as being relevant. Accordingly, the Tribunal decided that the provisional equidistance line should be adjusted so that, due to the concavity of the coast, the delimitation line did not cut off the seaward projection of Bangladesh's EEZ and continental shelf. The Tribunal emphasised that this adjustment had to be done in a balanced way so as to avoid drawing a line having a converse distorting effect on the seaward projection of Myanmar's maritime zones. In the end, by 21 votes to 1, the Tribunal drew an adjusted equidistance line as the boundary in the EEZ and the continental shelf.

Delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles

Every state that claims a continental shelf beyond 200 nm (often referred to as "outer continental shelf"), is required to limit its outer edge in accordance with Article 76. Such a limit could be, for instance, 350 nm from the coast. Upon delimiting the outer limit, every state is required to submit information about the limit to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf ("Commission"), which is a body under the UNCLOS. The final and binding outer limit of the shelf must be established by a coastal state on the basis of the recommendations of the Commission.

There could be an issue of delimiting the lateral boundary (as opposed to outer boundary) of the outer continental shelf between two adjacent states such as, Bangladesh and Myanmar. In addition to the delimitation of the territorial sea, the EEZ and the continental shelf, Bangladesh submitted to ITLOS the issue of the delimitation of the lateral boundary of the outer continental shelf. Myanmar, however, argued that the Tribunal either lacked jurisdiction or, if it had jurisdiction, it should decline to exercise its jurisdiction in respect of lateral boundary until the outer limits of the shelf had been established on the basis of recommendations of the Commission. The Tribunal decided that the fact that the outer limits had not been established did not preclude the Tribunal from discharging its obligation to adjudicate the matter.

Bangladesh argued that it alone was entitled to the entire continental shelf beyond 200 nm because the outer continental shelf was the natural prolongation of Bangladesh's land territory. Myanmar argued that the controlling concept was not "natural prolongation" but the "outer edge of the continental margin." The Tribunal rejected Bangladesh's claim that Myanmar was not entitled to a continental shelf beyond 200 nm.

In the end the Tribunal held that the adjusted equidistance line delimiting the EEZ and the inner continental shelf would continue in the same direction delimiting the outer continental shelf of the two states until the line reached a point where the rights of third states might be affected.

Disproportionality test

Having established the maritime boundary line, the Tribunal checked whether the line had caused any significant disproportion by reference to the ratio of the length of the coastlines of the two states and the ratio of the maritime area allocated to each state. It noted that the length of the relevant coast of Bangladesh was 413 kilometres, while that of Myanmar was 587 kilometres. The ratio of the length of the coasts was 1:1.42 in favour of Myanmar. The adjusted equidistance line allocated approximately 1,11,631 square kilometres of sea area to Bangladesh and approximately 1,71,832 square kilometres to Myanmar. The ratio of the allocated maritime areas was approximately 1:1.54 in favour of Myanmar. The Tribunal concluded that this ratio did not lead to any significant disproportion in the allocation of maritime areas to Bangladesh and Myanmar relative to the respective lengths of their coasts.

Conclusion

The preceding discussion clearly demonstrates that the outcome in the case was a balanced one, where neither party won or lost completely. Of course, all of us in Bangladesh congratulate our government for its bold decision to refer the maritime delimitation to ITLOS, which has resulted in a clearly defined maritime boundary between the two neighbouring states. We also thank the government for selecting a team of distinguished counsel and experts who ably represented Bangladesh in the case, leading to a fair result. However, claims of a total victory by Bangladesh over Myanmar are nothing but a distortion.

We should, instead, celebrate the success of both countries and, above all, celebrate the victory of international law, which provided a precisely defined maritime boundary between the two friendly neighbours and by doing so allowed both countries the opportunity to use the resources of the sea for the benefit of their people.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments