Freedom “on-air”

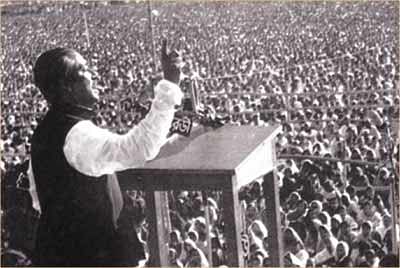

Bangabandhu delivers the historic speech of March 7.

Ashfaqur Rahman Khan, a retired Deputy Director General of Bangladesh Betar (radio), was among the witnesses to the turbulent times of the '70s. In an exclusive interview with The Daily Star he narrates the hair-raising experience of those days at the radio station and the broadcasting of the historic speech of Bangabandhu on March 7, 1971.

“There was resentment brewing up among the two wings of Pakistan. During the tidal wave and natural calamity of November 12, 1970, it was further evident that the Pakistani rulers were indifferent about erstwhile East Pakistan. On February 28, 1971, after returning from an official picnic we saw military guards posted at the gate -- 'it was for security reasons' they said.

“On March 1, while we were relaying a cricket match from the stadium there was an announcement in news that president Yahya Khan had postponed the assembly session. News was broadcast centrally from Karachi then. No sooner was this announced, you could literally feel the wave of fury that spread across the ground. Then there was an utter explosion of the public sentiment, the match was hastily abandoned and the crowd started to pour out of the stands and torch whatever they could find as a protest against Yahya's orders.

“Meanwhile the undisputed leader of the country, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman addressed a press conference and announced the non-cooperation movement from that very day,” said Rahman. Practically the whole country had come to a stand still and section 144 was implemented after dark.

Added Rahman, “From March 4, all the radio stations, which were directly under the central government, defied all regulations and changed its 'Station Call' from Radio Pakistan to 'Dhaka Betar Kendra'. The other stations in Chittagong, Khulna, Rahshahi, Sylhet and Rangpur followed the lead.

“At this important juncture the then-Regional Director of radio, Ashrafuzzaman Khan played a vital role in the history of radio of the country,” Rahman went on. “From this day onwards, under the able leadership of Ashrafuzzaman Zaman, we brought about a complete change in the schedule and started to broadcast news, documentary, commentary and patriotic songs. News editor Saiful Bari played an important role during this time.

“Meanwhile a nucleus team was formed with programme officers Mabzulul Hossain, Ahmeduzzaman, Mofizul Huque, Ashfaqur Rahman Khan, Nassar Ahmed Chowdhury, Kazi Abdur Rafique, Bahram Siddiqui, Shamsul Alam, Taher Sultan. We were given orders to face any eventuality and we stayed during late hours in shifts at the radio station.”

Rahman went on to add, “During this time, the agitated students and politicians, journalists and intellectuals had been urging the leaders to take immediate steps to declare Independence. The artistes had decided to boycott the radio, but we were able to convince them that the only option for us was to stay united.

“Soon after, as we know, the artistes formed the 'Bikkhubdo Shilpi Shomaj'. The artists, journalists, painters took the word to the people, performing on the roads, turning every vantage point into an impromptu stage.

“On March 7, the historic day, it was still undisclosed that we would broadcast the speech live. An OB team (outside broadcasting) was positioned at the Race Course Maidan, now known as Suahrawardy Uddyan. Throughout the day we played patriotic songs. When the time for the broadcast came, we put the telephone receivers down to avoid phone calls from the military authorities.

“Meanwhile there was a tense situation everywhere. Ashrafuzzaman was constantly in liaison with Bangabandhu. He was at the stage and Bangabandhu was supposed to arrive at the Race Course Maidan to deliver his speech at 2pm. At the station, seconds seemed like hours as the clock ticked away and we waited impatiently to relay the speech, live.

“Despite all our well-laid plans, disaster struck minutes before the speech was on. An official had forgotten to take one telephone of the hook and the call came from the higher authority as we'd feared. Someone brought in a chit, ordering us not to broadcast anything on Sheikh Mujib until further notice.

“However, by 2:35pm Mujib had reached the venue and began his speech to the nation and we were still in a deadlock on whether we could broadcast the speech or not. I was at the studio end as we tried wholeheartedly to contact Ashrafuzzaman for his final orders from Mujib.

“The next few moments were turning points. Ashrafuzzaman went on to the stage to pass on the message to Bangabandhu that we were not allowed to broadcast. He changed his address spontaneously by repeating this to the thousands gathered, urging all from that moment to stop working for the government. Ashrafuzzaman immediately asked us to leave work and come out of the heavily guarded radio station. From there we practically ran to the racecourse. By a stroke of luck, we had an emergency portable recording gear at the stage to record the historic speech.

“There were transmitters at Kalyanpur, Savar and Nayarhat from where the emergency transmission was carried out in case the main station failed. So when we came out of the office we asked the people in charge of the transmitting stations to evacuate the place.

“It was for the first time in the history of radio in our country that the transmission came to a total halt.

“Quazi Akhtaruzzaman of the Daily Ittefaq and Mirana Zaman a cultural activist and a staff of the then Radio Pakistan were instructed by Ashrafuzzaman to keep the historic speech in their steel cabinet. At a time when such an act could have led to any untoward incident--they held on to the document. Later on it was passed on to the officials of the Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra,” continued Rahman.

“The very next day, early in the morning we received orders to broadcast the speech at 8:30am and we resumed our broadcast.

“That day was a milestone for more reasons than one. The mood in the stations became defiant and bold. People worked round the clock gathering and relaying news, documentary, speeches--anything that would come to the aid of the country. The optimism from that room seemed to become contagious over the airwaves as it carried news of hope to people in the remotest corners. From muddied trenches to now-empty living rooms, the radio became the day-to-day companion, the one link that tied everyone together,” said Rahman.

If it took 3 million courageous lives and countless tragedies to win our war, what we should not forget is that it also took a group of dedicated people, who risked it all to keep the airwaves and the spirit of the country alive through it all.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments