“Just narrating a tale with no purpose otherwise is superficial”

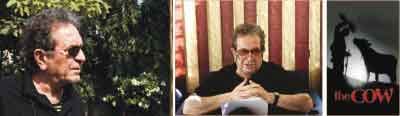

Photo: STAR

The septuagenarian Iranian filmmaker -- whose second film “Gaav” (1968) is considered to be the stepping-stone in 'Iranian New Wave' -- is in town to attend the 12th Dhaka International Film Festival. In a freewheeling conversation with Jamil Mahmud and independent filmmaker Shibu Kumer Shill, the iconic helmer talked about his four-decade-long journey in cinema.

“Gaav” is a pioneering film from the 'Iranian New Wave'. Can you elaborate on this?

Mehrjui: I feel fortunate that it's considered significant in the history of Iranian cinema. Before the Revolution (1979), we started the New Wave and “Gaav” was the first film that earned both commercial success and critical acclaim. Although, Golestan's (Ebrahim Golestan; pre-Revolution Iranian filmmaker) films had been screened at international festivals, “Gaav” was much talked about at Venice, Cannes and Berlin and won major awards.

“Gaav” was banned in Iran for almost two years. So I smuggled a copy of the film through a French friend. That's how it made it to Venice and earned fame. Suddenly Iran became famous in global cinema. Yet, the film remained banned in Iran until the Festival of Shiraz in 1970. The film premiered in Iran at that festival. The response was great.

Did you exchange views with your contemporaries such as Masoud Kimiai and Nasser Taqvai on the New Wave?

Mehrjui: We were good friends. We were always together. Kimiai and I started almost at the same time. Like “Gaav”, Kimiai's second film “Qeysar” also attained success but it was more commercial. Both films were screened at Iranian festivals and they, sort of, divided the critics. Some loved mine, whereas some praised “Qeysar”. They induced a lot of discussions and debates. Before these two films, Iranian cinema was purely commercial -- with a lot of singing and dancing and imitations of Indian cinema.

There's heavy use of metaphor in “Gaav”, and it presents a complex philosophical premise. What made you delve into philosophy?

Mehrjui: Well, I was always attracted to movies that had philosophical depth. I was very much impressed by Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni, whose films had different layers of interpretation. Those are the kind of films I was interested to make. The story of “Gaav” had that philosophical dimension.

“Gaav” is the story of a man whose cow is very dear to him. When the cow suddenly dies, he changes so much psychologically that he somehow finds himself to be the cow. This idea of love/affection -- dissolving into the object of one's love -- is a theme, which had been repeatedly expressed by poets like Hafez, Omar Khayyam and Maulana Rumi.

You changed your major at UCLA. You wanted to study Films, but graduated in Philosophy. Why?

Mehrjui: At UCLA, the emphasis was more on the technical aspects of cinema. They tried to create Hollywood type directors. This attitude did not attract me.

For me, just concentrating on cinema was not enough. I had a course with Jean Renoir, who helped me a lot. I was more interested in theoretical aspects rather than those technical subjects.

Some of your protagonists, such as Hassan (from “Gaav”), Pari, Hamoun and Banoo deal with dialectical crisis regarding their respective existence. Do they, in some way, represent the person Mehrjui?

Mehrjui: Not necessarily. But there are always certain aspects of my life, my temperament or my attitude towards life that are reflected in my films, often unconsciously. “Hamoun” is sort of autobiographical, but not exclusively. All of my films deal with existential issues. They deal with the existence of individuals and the crises the protagonists are thrown into. The situations force them to change their lifestyles in order to attain a new sense of awareness.

It's more or less like Carl Gustav Jung's “the individuation process”. An individual undergoes a situation in which s/he suffers a tremendous amount of suffering. This causes him/her to become a new person with higher level of consciousness. My films present situations like this.

What are the main reasons behind the global success of Iranian cinema?

Mehrjui: Alternative/art house films from Europe and the US are more or less banned in our country. Because of this prohibition, all the theatres are obliged to show local films. Iranian cinema, because of the strict control by the government, deal with human relationships. They are essentially simple films on the exterior. Iranian cinema has become successful globally, because it's still following the traditional trend of art films. And we have the opportunity and necessary investment to produce such films.

Minimalism is very apparent in Iranian cinema. Why so?

Mehrjui: Minimalism is a form/method, not content. Our cinema started with small funds, so we initially dealt with simple stories, featuring modest characters with humble backgrounds. That is why it seems minimal.

What is your impression of the third generation Iranian filmmakers? Are they capable of carrying on the legacy established by Abbas Kiarostami, Dariush Mehrjui and Mohsen Makhmalbaf?

Mehrjui: Yes, why not? I'm very optimistic. A young filmmaker has emerged, Asghar Farhadi, whose films are very good, almost at the same level as ours. I hope that his films would only get better. In our culture, the influence of literature and poetry is great. Thanks to all the filmmaking schools, inspiring literature and encouraging ambiance, aspiring directors are likely to make good films.

Several of the third generation Iranian filmmakers are in exile at present. Do you think they've chosen the right path?

Mehrjui: No, I don't think they have chosen the right path. I was in Hollywood and I had the opportunity to make films there. I was in Paris for four years and made films over there as well. But it didn't satisfy me. I came back to Iran because the ideas that'd encourage me to make films were here. My filmmaking becomes meaningful here.

What, according to you, is the main purpose of a film?

Mehrjui: Filmmaking is a work of art. The main purpose of a film, for me, is to reach out to the audience and try to stimulate their awareness. Just narrating a tale with no purpose otherwise is superficial.

Do you follow a process when choosing stories for your films?

Mehrjui: No, I don't have any particular method. I usually write down my ideas for stories. When I want to make a new film I go over those ideas and contemplate the possibilities of doing such a film. That is how I choose my storyline -- either I write it myself or collaborate with friends.

How important is combining craftsmanship and ideas to make a film a success?

Mehrjui: Literature is a good source for cinema. A good screenplay is very important. You pick up a story and you don't know what to do and you write down a bad screenplay. This story may be written by you or someone else. I think a good filmmaker dominates the screenplay to turn it into a good film.

In “Santoori”, you've shown a darker side of Iranian society. The subject (drug abuse) is bold and unique in Iranian cinema…

Mehrjui: Drug addiction is a very serious problem in our country. In the past decade, it has gotten worse. The government tries to fight the situation, but somehow hasn't been successful. I wanted to address this issue.

You have faced heavy censorship throughout your career. Are Iranian filmmakers still going through such censorship?

Mehrjui: Every single film of mine has had to face censorship, both before and after the Revolution. “Banno” was banned for nine years and “The School We Went to” for 11 years. When the films came out nothing had happened. So I don't know why the authorities banned them. Yes, Iranian filmmakers have to face strict censorship, and it's getting worse.

What kind of political responsibilities are apparent in your works?

Mehrjui: Politics is everywhere. Every film is political in this sense. I don't like directly political films that preach one ideology or the other. I think that cinema or art should be above this. Cinema is like poetry, and poetry cannot take sides. Art should not be a simple tool of propaganda.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments