The task that awaits in Durban

Photo: Magictorch / Getty Images

A year ago, in a swirl of pessimism, the UN held negotiations on climate change in Cancun. After Copenhagen, it seemed that the principles of international negotiation itself were on trial.

Expectations were low. But out of the acrimony arose a new consensus. The world agreed to keep global warming to below 2C.

This is significant. The world does not agree that often. We have few global agreements and just one global organisation. Next week, the UN will convene the next round of talks on a global climate treaty.

Unfortunately, for many countries times could not be harder. Europe faces a massive currency crisis. The United States is preoccupied with jobs and growth. The Middle East and North Africa are consumed by questions of political reform.

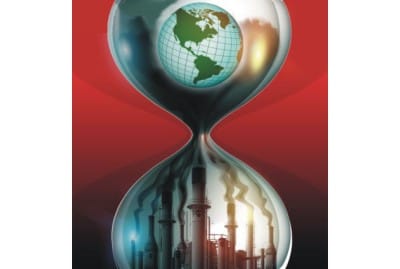

Last year, our focus was to keep the show on the road: as long as you are talking, there are options. But time is running out. As the International Energy Agency noted this month, the window for meaningful action on climate change is now measured in years, not decades. The science tells us we must bring down global emissions by 2020.

In Cancun, we began to put in place a global architecture to monitor emissions and support developing countries in tackling climate change. But a more fundamental question went unanswered. Where are the international talks heading?

Are we moving to a legal agreement committing major emitters to emission targets, or countries voluntarily pledging to take action?

My answer is simple: a global deal covering all major economies is a necessity. This was important enough to both partners that it was in the Coalition Agreement. The UK remains a steadfast advocate of a legally binding agreement under the UN.

Durban will not be our eureka moment. But there is already a legally binding deal in place: the Kyoto Protocol. In 1997, 37 major economies -- including Japan, Russia, Canada, Australia and the EU -- formally committed to cutting emissions. The EU has already surpassed its Kyoto target.

The first Kyoto Protocol commitment period ends next year, and Japan, Russia and Canada have said they will not enter a second.

The EU, on the other hand, wants just that. But if the EU alone signs up -- without comparable commitments from major emitters including the US, or China, Brazil and India -- then we won't have achieved much.

Together with the rest of the EU, I have made it clear that I am keen to secure a second commitment period of Kyoto. But others must commit to the global legal framework the world needs. Ultimately, Durban is about the movement others make.

Kyoto provides the basis of the rules we need to manage a destabilising climate. If we have learnt anything from the financial crisis, it is that clear rules implemented properly can prevent the toxic build-up of risk. Durban must not be the end of Kyoto.

Rules work. A recent survey of large global firms found that 83 per cent of business leaders think a multilateral agreement is needed to tackle climate change, but only 18 per cent thought a deal was likely. Businesses want certainty; people want action. Only the politics lags behind.

A commitment to a new agreement will provide that certainty. But the pledges on the table are not enough. In Durban, we should agree that we must close the gap. We can identify actions we can take and build momentum towards a major review of ambition. We can also build on the system we use to measure and verify emissions cuts.

We must do more on long-term financial support for developing countries, and establish the Green Fund. And we must continue the work already underway to reduce emissions from deforestation.

Next year I will be pressing for a more ambitious EU emissions target: a 30 per cent reduction by 2020.

Milton Friedman once said "our basic function is to keep good ideas alive until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable". That is a good description of the task that awaits in Durban.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments