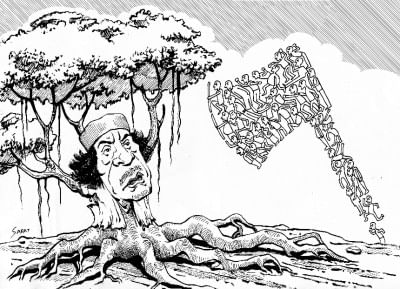

Gaddafi and all those nasty men

Photo: SADATUDDIN AHMED AMIL

Muammar Gaddafi's was a sorry end, macabre in its dimensions and tormenting in its imagery. For many around the world, he deserved to be pushed from power, for all the right reasons. But he certainly did not deserve the collective villainy that was visited upon him in the last few moments of his life. That he concealed himself inside a sewer pipe, in the hope that no one would find him, was a clear demonstration of the principle on which irony usually works. Towards the end of his regime and even after he had been run out of Tripoli, he kept to his belief that those who were busy trying to topple him were rats. In the end, it was he who was caught in rat-like behaviour. Even so, those who kill a rat are not men who teach us anything edifying about life.

Way back in the late 1970s, the Islamic revolution in Iran was considered by many as the beginning of a fresh new era of freedom for a long-suppressed people. The Shah was on the run, his empire lay in ruins and men like Abolhassan Banisadr gathered around Ayatollah Khomeni to give their country a new sense of direction. Not many were aware, though, of what the clerics would soon be up to. The new regime unleashed bloodthirsty men like Ayatollah Sadegh Khalkhali, who soon went round picking on loyalists of the fallen Shah and then picking them off. They killed the good and the bad, in the name of the Almighty. The polished Amir Abbas Hoveyda was swiftly dispatched, to the world's horror. The mullahs remained unperturbed.

The lesson of history is simple. Leadership which mutates into symbols of terror, which turns grasping in attitude, provides the perfect reason for oncoming chaos. Peaceful protests turn into militancy; crowds demanding democratic change decline into the state of mobs baying for blood. And those who have ruled for decades suddenly discover that their country is not with them any more, that the silent anger of nations is ready to swallow them up. This kind of cannibalism, running parallel to dictators' rising arrogance, ends up smashing the citadels of power, burning down the tents of entrenched authority. That was how Nicolae Ceausescu's Romania came crashing down in December 1989. The mob would not let him off the hook. He and his wife were cut down in cold blood.

There is forever the ugly about human nature. It is always ready to break into the nasty, willing to forget the good deeds that their fallen leaders might have accomplished at an earlier stage of their hold on power and remember only the dark symbols of repression and things kleptocratic they turned into over time. You do not blame men and women for shedding their reserve and become, in a frenzied moment, creatures driven by animalistic indignation ready to tear apart all the symbols of fallen authority. It was animal screams that punctuated the Taliban capture of the ousted Najibullah and his brother in Kabul. The two men were stripped, beaten, tied behind the wheels of a jeep and dragged all over the place by men who had seized power in the name of faith. Najibullah's corpse was hung in the town square. Men who had been sensible beings the previous day now gloated over the spectacle of their dead leader. Afghanistan was on its way to becoming a kingdom of organized banditry.

But villainy is not always part of the character of a crowd. It sometimes comes to individuals or groups who somehow do not stay far from thoughts of driving the knife into their enemies. Samuel Doe, the petty sergeant who threw Liberia into chaos in the early 1980s through his violent coup (he had the ministers of the fallen government lined up beside the beach and shot), let out horrific screams as his enemies tore his body parts into pieces one after the other years later. Doe, having ruled by violence, perished in even bigger violence. Charles Taylor would carry on with the trend, until the world stopped him and bundled him off to an international tribunal for trial.

Entrenched leadership is always a recipe for disaster. The rise and fall of Muammar Gaddafi remains proof of how idealism, when it is supplanted by thoughts of immortality, dwindles quickly into depravity. It was a young, bold and enterprising Gaddafi who pushed a feudal monarchy from power in Libya in September 1969. Revolution was what it was called. An unabashed admirer of Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser, Gaddafi gave off sparks of brilliance that were to be. Libya went through soaring change. That magical moment when a leader clicks with his people had arrived.

And then came the fork in the road. Gaddafi took the wrong turning, began doing all the wrong things and soon proved to his people, to the world, that Libya was less a country and more a personal fiefdom. He paid the price.

But if Gaddafi had mutated into a villain, those who battered him to death only proved in practice what Hobbes had once said in theory -- that men were nasty, brutish and short. The manner of Gaddafi's death remains a thick, dark stain on the putative democracy that Libya means to be -- and may not be in the end.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments