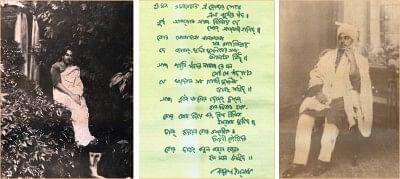

The All-embracing Poet

Kazi Nazrul Islam, known as the 'Rebel Poet', is probably the most uncompromising dissident in Bengali literature. Many writers and intellectuals, who started with commendable patriotic zeal and revolutionary ideals, often got burned out along the way, either becoming reactionary fanatics or living on the paychecks handed out by governments and financial institutions. But as an individual and also as a public figure, Nazrul remained acutely sensitive to suffering of the masses. He gave public speeches and addressed multitudes, edited newspapers, was a performing artiste, and went to jail for the relentlessness with which he protested dictatorships and colonialism. All these make it hard to give an overview of the great poet in a few words.

One of the most progressive intellectuals in our history, Nazrul was born in a remote, backward village in West Bengal and hardly enjoyed the shelter of a family since his adolescent years. After the demise of his father when he was only ten, he had to support his family by working at the local mosque. He later joined a travelling theatre troupe and learned (as opposed to studied) Bangla and Sanskrit literature when he was very young. He composed his masterpiece “Bidrohi”, one of the most discussed and studied poems in Bangla language, when he was only 22.

Nazrul is a romantic in essence. But his romanticism and his poetic vision do not alienate his works from the pressing issues of the real world. It is understandable that his spirit of rebellion actually stems from his rootedness and acutely emotional mind. Asked to comment on this conjecture, Hasan Al Zayed, an assistant professor at the Department of English at East West University, said: “It is necessary for a rebel to be romantic. Those who are worldly wise often fail to see beyond 'state of things'. One has to be a romantic to recognise that a better world is possible. But Nazrul's was a rooted romanticism, not a wishy-washy one.”

The complex nature of Nazrul's works makes it impossible to associate a particular tradition to his works. Following a particular tradition was anathema to him. He was secular; but he also embraced his Bengali Muslim identity. However, his political identity is a secular one, embedded as it is in a worldly politics, which stands in stark contrast with the elitist communalism of Bankim and others.

Nazrul made extensive use of Arabic and Persian words in his writings -- a defining characteristic of the puthi literature, which was popular among Bengali Muslims, most of whom were illiterate at that time. In a comprehensive essay on the diction of Nazrul, eminent writer and thinker Ahmed Sofa pointed towards Nazrul's use of the words that were not heard outside Muslim households. Sofa viewed Nazrul's language in the context of a broader political perspective and pointed out that he established “the social language of the Muslims as the language of literature.” And he made “Bengali language and literature a territory of both Hindu and Muslim” [translated].

Ironically, it was a part of the Muslim community that declared him a 'kafer' [sacrilege].

In “Bidrohi”, Nazrul invoked images and allusions (i.e. jahannam, ashur etc) from both Hinduism and Islam with such eloquence that the poem remains unparalleled in Bangla literature. “He composed some of the best songs about Islamic renaissance, but at the same we hear him singing “Shayama Naame Laglo Agun”. He appropriated and made use of all the patriotic and humane elements of both religions,” said Sumon Chowdhury, a musician and a Nazrul enthusiast.

In Bangla literature, no other poet or writer has been more successful in creating a bridge between religion and culture.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments