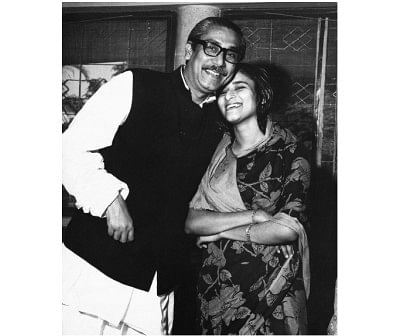

Sheikh Mujib and the Six Points

Photo: Archive

"O judgment! thou art fled to brutish beasts,

And men have lost their reason. Bear with me;

My heart is in the coffin there with Caesar,

And I must pause till it come back to me."

--- (Mark Antony in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, Act 3. Scene II)

On this day, I am reminded of Mark Antony's passionate eulogy for the fallen Julius Caesar, who was assassinated in a conspiracy hatched by some of the people he trusted. In a similar fashion, thirty six years ago, under the cloak of darkness, a group of misguided disciples of Brutus rubbed out the life of our Father of the Nation. In his speech, Antony alludes to some of the charges brought up by Caesar's detractors, and he laments:

"The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones;

So let it be with Caesar."

As Antony aptly reminds us, good deeds are often buried with the fallen heroes. I write this short memoriam as an offering of admiration for the Six Points manifesto, one of Bangabandhu's many achievements and legacy, and offer a personal perspective on its influence on young economists like myself in our formative years.

It will not be an exaggeration to assert that the Six Point programme, first enunciated by Bangabandhu in 1966, played an important role not only in the political landscape of Pakistan, but also in the education of economists of a whole generation. Many, like us, went through four years of economics in high school and college in the late 1960s, learning about market equilibrium, factors of production, and the structure of the economy of Pakistan. But none of the textbooks offered us any idea on some of the fundamental questions on our minds:

1. Why is the industrial sector growing faster in the West than in the East?

2. What are the mechanisms through which resources are transferred from the East to the West?

3. If jute and jute products are the main exports of Pakistan, what accounts for the publicized "foreign exchange constraint" that is blamed for the low rate of investment in the East?

4. Last, but not the least, if Pakistan is accumulating such huge foreign debts, why is this influx of "foreign aid" not improving the lot of the masses in the East?

The Six Points opened up the learning opportunity for those of us entering Dhaka University at the end of the so-called Decade of Development foisted on us by the brutal Ayub Khan regime. It opened our eyes to the degree and extent of the exploitation of the East in the name of national integration. The columns in the weekly journal Forum and the Sunday newspaper Holiday spelled out how the two wings of Pakistan had really become two economies. And we understood how this had happened within the short span of twenty years of Pakistan's existence.

I remember that my fellow classmates in the Economics Department of Dhaka University --- Taki, Nisar and Shamim --- were fired up by the ongoing discussion on economic issues in the national arena prior to the 1970 elections, and worked tirelessly to revive the departmental journal, Optima. When they asked me to submit an essay, I did not hesitate and wrote my first analytical paper on the genesis of the "two economy" theory and the ever-widening disparity between the two regions of Pakistan. I hardly need to mention that I borrowed heavily from the literature that stemmed from the Six Points manifesto.

In his comments on the Six Points, M. Rashiduzzaman noted in a paper in 1970 that "Sheikh Mujibur Rahman gave a new turn to Pakistan politics when he put forward a six-point program which would allocate maximum power to the province, and at the same time reduce the strength of the Central Government". However, it would not be too far-fetched to assert that the Six-Point program also changed the national discourse in the economic forum in the dying days of Pakistan. Points Three through Five brought the issues of capital flight, foreign exchange earnings, and single currency to the fore, and forced the ruling coterie to recognize that the struggle of Bangladesh's people was not just about political power, but also about economic emancipation. Bangabandu's goal was not only to take back political power from the ruling clique of the West, but also to give the people of Bangladesh better control over their economy, job prospects, and their own pocket book.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments