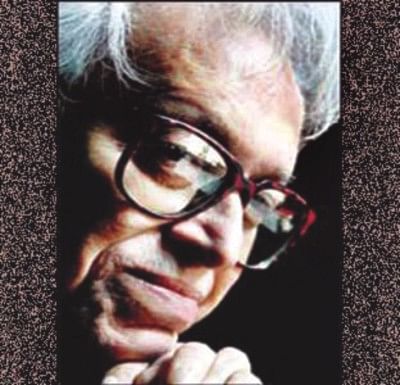

Shamsur Rahman . . . in the memory

Shamsur Rahman, the doyen of Bangla poetry, breathed his last on August 17, 2006. No death ever made me sadder.

My readers are certainly aware that I unequivocally admire a few Bangladeshis. Shamsur Rahman is one of them. Every year I would write on him before his birthday, especially during the last several years of his life. As usual I wished him many happy returns of the day on October 23, 2005, when he turned 76. Little did I know that he wouldn't reach his next birthday. Man proposes, God disposes. Like millions of his admirers, I was so fond of him that I thought he would never die! How could one of the best poets of the Bangla language, such a nice person, die so early? He never glorified death and wanted to live for a thousand years. I thought he deserved to live for at least a hundred years.

Before his death the poet was sick for a long time. Our government failed to send the poet abroad for treatment. The Prime Minister and the Leader of Opposition couldn't make time to see him at the hospital. Our poets and writers, intellectuals and cultural activists couldn't form a committee to collect funds for his treatment. Our rich people can buy BMWs and Porsches but they have nothing to do for our finest of poets, a living legend. Why couldn't his affluent relatives send him abroad? I asked myself. I knew his family was in financial hardship. He was too refined a person to seek help from others.

August is our cruellest month, not April. August has snatched away Bangabandhu, Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam. Humayun Azad left us in August too. Now the handsomest and most popular of poets is gone. Bangladesh's premier modernist is no more. He died on Thursday. I woke up on Friday morning with a heavy heart. Why am I feeling so sad? I asked myself. I got ready for my morning walk, dressed in black. From our adda we would rush to the Shaheed Minar to pay our last respects to the poet. I had visited the poet in the hospital at noon on August 11. Tia Rahman, the poet's omnipresent daughter-in-law, was there. His eldest daughter and her husband were there too. Tia always nursed the poet like a mother. I found tears rushing to my eyes on seeing the frail poet on his hospital bed. The poet had talked a little that day and Tia was happy. The very sick poet didn't fail to look handsome, I noticed. I felt like touching him. And asking him, 'Are you leaving us this time? You can't! You simply can't!' There were the kind nurses and doctors, who were looking after the poet like his own children. People loved him, I assured myself. The Channel I reporter requested me to say something. I urged them to interview Tia. They talked to Tia and the doctors. I noticed that even the class four employees of the hospital were very fond of the poet. I felt very proud of them. Silently they prayed for the country's best living son.

At the Shaheed Minar we had a last glimpse of our dear poet. The presence of thousands of people made us happy. Politicians, poets and writers, teachers and students, cultural activists, working women, housewives, children people from all walks of life turned up to pay their last respects. Khan Sarwar Murshid, the poet's teacher; Sayeed Ahmed, Nirmal Sen and Syed Shamsul Huq shed tears like children. I took a long look at the poet and then turned my face away. Where was that pink handsome face? Where was the world's best smile? I shall never look at the lifeless face of a person so dear to me, I told Elias a little later in great sorrow. Meenakshi, slightly younger than the poet and the daughter of Buddhadev Bose, used to tell people that Shamsur Rahman looked like a Moghul prince. The prince was sleeping like a helpless child. Was this the face that Swati Ganguly, wife of Sunil Ganguly, found the handsomest among poets?

We rushed to Madhu's Canteen for tea. We waited for the janaza. The poet would be buried beside his mother at the Banani graveyard. His mother died in 1997 when he was sixty-eight. Kokhono Amar Makey is one of his finest poems and a great favourite with me since my youth. One of Dhaka University's most illustrious students is no more, I whispered to the beautiful trees surrounding me.

Shamsur Rahman was every inch a Bangladeshi poet. He was our first great modernist and the best too. Cosmopolitan and yet a Bangladeshi to the core of his heart, he was progressive, secular and anti-establishment. He was proud of our history and our culture. He could rightfully claim credit for lifting Bangladeshi poetry to the level of world poetry. Man's welfare had been his primary concern.

Shamsur Rahman wrote brilliant prose too. His novels, short stories and essays are the proof. I wanted him to write more stories. He dealt effortlessly with surreal elements in his stories. His 'Smritir Shahar' (The City of Memories) is a wonderful account of his boyhood in Dhaka. I feel that reading this book is a must for all teenagers and all Dhaka-lovers. His prose is lucid, lyrical and poetic. He has also been a very good composer of children's rhymes.

Although Shamsur Rahman wrote his best poetry and prose as a young and middle-aged man, he surprised us with a brilliant poem every now and then even as an aged man. He had an effortless entry into every corner of the world of our emotions. He was the best painter of our happiness and sorrows, our loneliness and nostalgia, our angst and boredom. Our 1969 movement for democracy, our 1971 war of independence, our 1990 movement for the restoration of democracy are all there quite vividly in his poetry. He was our conscience, the nation's philosopher and guide. Uncompromising in so far as the ideals of our liberation war were concerned, he symbolized our hope, belief and trust.

Dr. Khan Sarwar Murshid, his learned teacher at the Department of English, Dhaka University, wrote on the poet's 70th birthday that the young Adonis was a shy escapist, was fond of literary addas, was a free learner, was not fond of examinations and was certainly chased by many a Venus. He was very sensitive and very soft. He did get a degree and his results were quite good. But how he became an outstanding poet of man's happiness and suffering, how he became a wonderful painter of dreams, rebellions, love and death, how he created a superb, glowing language of deep and delicate discoveries is a long and surprising tale. Dr. Murshid feels that Shamsur Rahman's poetic contributions to our progress as a nation and during our crises is priceless.

And what did we, members of The English Department Alumni Society, write in our condolence message to the poet's family? We called him Bangladesh's premier poet and an icon of our freedom. We called his poems immortal. He was an aesthete and a rebel, highly respected and loved. In his own dignified way, he fought all oppressions and injustices. He was firmly rooted in his Bangladeshi milieu but was cosmopolitan at the same time.

Shamsur Rahman is no more but Bangladesh will not forget him for a long, long time.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments