Revisiting a people's struggle in its vocal totality

MILITANCY has been part of the Bengali political psyche. Add to that a dash of poetry, for poetry is what has consistently defined the Bengali, and what you then have is a powerful expression of nationalistic sentiments. Siddikur Rahman Swapon does, in the work under review, the very creditable work of reminding the nation not only of the various phases of political struggle it has gone through over the years but also of the stridency that was brought into that struggle at successive phases in history. The growth of Bengali nationalism, as it were, was fundamentally a rise of gradual political awareness among the people of this country. You could argue that nowhere around the world can you spot a society as radically inclined as Bengalis, for whom politics has historically been a ceaseless struggle against oppression at various stages of time. Go back to the seminal struggle for language that has come to be known as Ekushey. It was in February 1952 that political slogans first began to acquire a pattern, with such demands, voiced collectively by young Bengalis marching in defence of their language, as rashtra bhasha Bangla chai. It was, at that point, a simple enough demand. After 21 February 1952, though, it not only came by a new potency but also spawned songs that only intensified the militancy. Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury's amar bhaiyer rokte rangano Ekushey February and Abdul Latif's ora amar mukher bhasha kairha nit-e chaaye went a good many steps further in hastening the march to Bengali disillusionment with Pakistan.

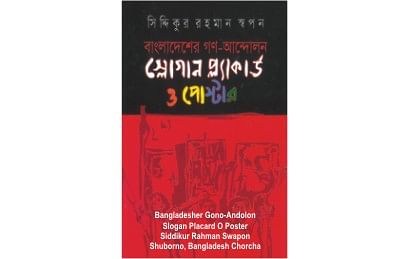

In Slogan Placard O Poster, Swapon essentially recapitulates history through explicating the background against which slogans came to define the rising political sensibilities of the Bengalis. And much of that history, apart from that consequent upon the shootings of February 1952, was forged in the era of Mohammad Ayub Khan and particularly through the student movement against the education commission report of 1962. On 17 September, students of Dhaka University led by Rashed Khan Menon brought out a procession. The placards carried in the march depicted the following slogans:

Daabir proshne aposh nai, shongramer bir chhatrashomaj tomader obhinondon and Ayub shahi'r rokter trishna ki mitbe?

The year 1962 was an eventful period in Bengali history. The Ayub regime placed Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy under arrest and made sure that other politicians remained unable to operate through the provisions of the Elective Bodies' Disqualification Ordinance (EBDO). Following Suhrawardy's release in the face of growing protests, a reception, where a young Sheikh Mujibur Rahman spoke, was organized to welcome the former Pakistani prime minister back to freedom. Quite a few posters were arranged at the venue of the meeting, with such slogans as Bhashani'r daabi desher daabi maante hobe, rajbondider mukti chai, nirapotta aaeen batil koro, gono dhikrito EBDO aaeen batil koro inscribed on them.

Slogans and posters leapt to a new dimension with the announcement of the Six Point programme for regional autonomy in Pakistan by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in February 1966. Indeed, the general strike observed all over East Pakistan in support of the Six Points on 7 June 1966 gave a significant impetus to politics in the province. Swapon notes that at that stage in history, a proactive Chhatra Union came up with certain slogans, among which was the pretty stirring, and courageous for its time, demand: Purbo Bangla-e purno ancholik shayottoshashon dite hobe. The struggle for democratic politics took a major leap forward with the announcement by the Pakistan government in late 1967 that it had unearthed the Agartala conspiracy case which involved altogether thirty five Bengalis. The conspirators, as the Ayub regime would make it known in January 1968, were led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, then in detention under the Defence of Pakistan Rules. As the proceedings of the case got underway, it became pretty obvious that the Bengali nation, in a radicalized manner, was beginning to spot in Mujib signs of their collective nationalistic future. Demands quickly began to arise for his release and for the first time the slogan, jeler tala bhangbo Sheikh Mujib ke aanbo, was raised on the streets of Dhaka.

Slogans and demands as etched on placards in the 1960s clearly had a rhythmic quality to them. Much like poetry, there was a resonance, a cadence as it were, in them. On 5 December 1969, on the occasion of Suhrawardy's sixth death anniversary, Mujib, free of the Agartala case and preparing the Awami League for the general elections scheduled for the later part of 1970, informed the nation that henceforth East Pakistan would be known as Bangladesh. The move swiftly led to a new slogan, nationalistic in tone and quite indifferent to the rest of Pakistan. In amar desh tomar desh Bangladesh Bangladesh lay broad hints of the future. This slogan would be raised in more vociferous form in March 1971 as Bengalis patently felt that their future lay in a free Bangladesh rather than in a Pakistan which refused to acknowledge their rights as confirmed by the results of the 1970 elections. In 1971, other slogans came up in quick succession as the political negotiations seemingly went nowhere. Bengali militancy took newer forms with such slogans as bir Bangali ostro dhoro Bangladesh shwadhin koro and tomar amar thikana Padma Meghna Jamuna. There was too the electrifying Joi Bangla, a call or slogan reverberating across the country, along with janatar shongram cholbe. Quite a good number of the slogans fashioned and raised on the steamy streets of Dhaka would subsequently be transformed into patriotic songs on Shwadhin Bangla Betar during the nine-month struggle for freedom between March and December 1971.

Siddikur Rahman Swapon brings to light an entire political landscape through going beyond Bangladesh and recovering the language of posters, placards and slogans as it revealed itself among expatriate Bengalis in 1971. In places such as London and New York, Bengalis through well-organised campaigns drew the attention of western and other governments to the systematic brutalisation of their compatriots in Bangladesh by the Pakistan occupation army. Stop genocide, Free Mujib, Try Yahya Not Mujib and Recognise Bangla Desh were recurrent themes for Bengalis abroad.

The work is a definitive addition to the record of Bengali political struggle. And that is so because of two important reasons. The first is that it builds up the tale of how a culture-driven Bengali swiftly transformed himself into a politically militant being. The second is the sheer admixture of poetry and politics which went into a rejuvenation of the struggle, first for autonomy and then for independence, in Pakistan's eastern province. It is the sense of history which comes alive here.

Sadya Afreen Mallick, eminent Nazrul exponent, is Editor, Arts & Entertainment, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments