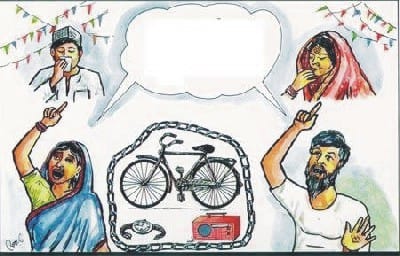

Dowry and extreme poverty

Photo: STAR

It is not uncommon for development practitioners to compare the impacts of dowry with those of cyclones, floods and other forms of natural disasters. Although dowry is not a natural and unpredictable phenomenon, it is something that has become engrained into the culture of Bangladesh over a relatively short period of time. The cycle of poverty is further entrenched through this continuing practice, which in turn is distorting the effectiveness of existing and continuing poverty reduction programmes.

In 2008, International Food Policy Research Institute cited dowry as the leading cause of poverty in Bangladesh, despite the ongoing efforts of numerous NGOs to curb the practice. Dowry has been traditionally analysed as a part of expanding personal rights of women within the broader poverty agenda, however, further work is required to understand its linkages with extreme poor groups.

This need for further understanding is gaining increasing importance as, over the last few years, the Bangladesh government, supported by donors, has undertaken a number of programmes tasked with eradicating extreme poverty. Some such programmes include shiree, the Chars Livelihood Programme, Urban Partnerships for Poverty Reduction and Brac's Targeting the Ultra Poor programme.

These programmes can be, roughly, separated between distributing fixed assets to households or raising awareness on individual rights and entitlements. Both of types of model attempt to improve household income generating capabilities and ultimately lift their beneficiaries out of poverty. These programmes have proved fruitful in the short-run, but a failure to grasp the debilitating effect of dowry may lead to critical long-term implications.

In rural areas, dowry is often the most important aspect of the marriage. Parents of young men and women spend a considerable amount of time negotiating the "right" amount before the start of the ceremony. Families struggle to raise this often hefty sum, as many people believe that it impossible to get married without dowry.

Research has shown that moderately poor families struggle to raise dowry through several different mechanisms, including taking multiple loans from micro finance institutions or by selling assets including land. In comparison, the extreme poor adopt a different set of coping mechanisms as by definition they have no land, limited assets, low levels of income and no access to micro-finance.

The extreme poor are dependent on the philanthropy and charity of the local community, where dowry is collected through a number of mechanisms including chadda or haat collections, high interest informal loans, and engaging in child labour.

However, the coping strategy is modified when an extreme poor household is engaged through a poverty reduction programme such as those mentioned above.

As extremely poor individuals start to reap the benefits from these programmes, through increased access to income earning opportunities and the creation of an asset base, their status in the community changes.

These individuals are no longer seen as extreme poor, and thus not worthy of charitable support; in many cases beneficiaries have been recipients of sizable asset transfers, while also being connected to and supported by an established NGO.

As a result of this transformation, these once extremely poor individuals adopt similar day-to-day coping mechanisms to that of other moderate poor households -- including the provision of dowry. This reality has, however, the potential to erode any gains that the project tasked with eradicating their poverty may have provided.

As the beneficiaries' position as moderate poor is often newly acquired, their footing in this class is relatively unstable and they are vulnerable to slide back into extreme poverty. This situation often comes true under the premise of the provision of dowry; individuals are forced to sell off their newly acquired assets, part with their meagre savings and any other project inputs they may have received, which in turn forces them back into extreme poverty.

Such a slide can have devastating effects on households; as the community still views the beneficiary as being supported by an NGO, they are reluctant to provide support as they did previously. In addition, other extreme poverty programmes are reluctant to follow suit since the individual remains a beneficiary from another programme. As such, these households fall into a further state of destitution. Such a situation poses significant questions over efficacy over these extreme poverty reduction programmes and their ultimate goal.

Without stronger actions and efforts to mitigate dowry, programmes aiming to lift the extreme poor out of poverty may actually increase the vulnerability of households, with the potential to push them deeper into extreme poverty than ever before. Dowry is not a natural phenomenon, and we should not treat it like one.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments