Gold as the ultimate bubble

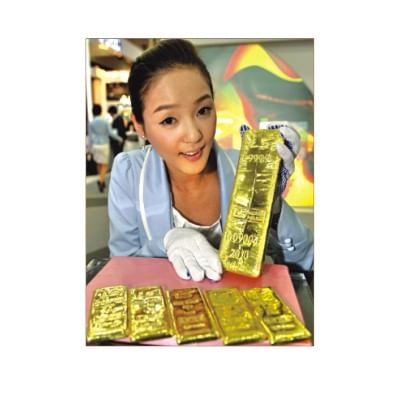

A promoter from South Korean metal refiner LS-Nikko shows a 12.5kg gold bar in Seoul. Photo: AFP

Billionaire financier George Soros this month repeated his warning gold is locked in the "ultimate bubble", and told investors bluntly it was "certainly not safe" in troubled times.

Soros was simply repeating a warning he issued at the World Economic Forum (WEF) back in February. At the time gold was trading at less than $1,150 per ounce. It has since risen to touch $1,300 this week, and is up more than 400 percent from its low of $252 in 1999. There is no end in sight for the bull run. Anyone who shorted gold back in February would be sitting on huge losses.

But while Soros himself warned gold was in a bubble, his hedge fund, Soros Fund Management LLC was one of the biggest gold bulls of the year, doubling its holding of shares in the SPDR Gold Trust at about the same time he was issuing his warning at the WEF in Davos. Soros is no longer involved in the management of the fund. But the apparent disconnect between the bubble warning and the bullishness of his fund will strike many observers as strange. In reality it illustrates the fascinating investment philosophy of one of the most successful financiers of the last 50 years and is the best way to understand what is really going on in the precious metal market.

REFLEXIVITY AND BUBBLES

Soros outlined his theory of price formation, and how bubbles inflate and collapse, in a brilliant book on The Alchemy of Finance, first published in 1987, but updated in 2003. It remains one of the clearest, most incisive explanations of how and why bubbles occur, and shows how profiting from the "madness of crowds" has been pivotal to his success.

In particular, Soros rejected the prevailing idea that "market prices are ... passive reflections of the underlying fundamentals", a dogma he dismissed as market fundamentalism, or that there were stabilising forces which would automatically drive prices back towards equilibrium.

Instead, Soros propounded a theory of "reflexivity", in which fundamentals shape perceptions and prices, but prices and perceptions also shape fundamentals. Instead of a one-way, linear relationship in which causality flows from fundamentals to prices and perceptions, Soros developed the theory of a loop in which prices, fundamentals and perceptions all act on one another.

"I contend that financial markets are always wrong in the sense that they operate with a prevailing bias, but that the bias can actually validate itself by influencing not only market prices but also the fundamentals that market prices are supposed to reflect".

Later he writes more bluntly: "[The efficient market hypothesis and theory of rational expectations] claims that the markets are always right; my proposition is that markets are almost always wrong but often they can validate themselves".

Beyond a certain point, self-reinforcing feedback loops become unsustainable. But in the meantime positive feedback causes bubbles to inflate further and for longer than anyone could have foreseen at the outset.

Soros cites numerous examples of self-validating behaviour -- ranging from the conglomerate boom of the 1960s and real estate investment trusts (REITs) in the 1970s to the technology boom and the rise and spectacular fall of Enron and WorldCom at the end of the 1990s and start of the 2000s. Each was heralded at the time as a "new paradigm".

But none is more fascinating than his explanation of the dynamics of the REITs bubble in the early 1970s. Because Soros recognised the potential for a bubble early and published a research note advocating investors should get aboard the trend.

In the debate about whether markets are a "weighing machine" for discovering true fundamental value or a "voting machine" which records the popularity of certain theories and the mass of the crowd, Soros came down firmly on the side of the voting machine.

Crucially, the successful speculator responds to bubbles not by shorting them and waiting for stabilising forces to drive the market quickly back to some fundamental value, but by identifying them early and riding the wave, hoping to get out before the whole edifice finally comes crashing down.

Reading people is as important -- if not more important -- as understanding the fundamentals of an asset itself.

In this world, gold is the ultimate bubble because apart from the cost of actually digging it out of the ground it has almost no real fundamentals other than price itself.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments