Market-based solutions for Dhaka's traffic headaches

I drive to work each day, which is about thirty miles each way. Without over-dramatising my situation, I can say that no two days are the same as far as commuting and beating the traffic is concerned, and this is in part due to the daily variability in the traffic condition, which is truly an unknown factor in the daily challenge to get to work and come back in the shortest possible time.

I have sliced and diced the cost of traffic congestion for a number of years, and as much as I dislike sitting in traffic I'd hate it even more if all efforts to curb the traffic congestion in Dhaka come to naught due to errors of omission and commission. I write this essay to shed some light on this universal problem and offer some pointers.

Commuters, whether in Dhaka, London, or any other major city, in the world face a number of identical conditions. First and foremost are the variability and the uncertainty of traffic flow on the highway, or the back roads we take each day, some by choice, some out of necessity and often on the spur of the moment when the regular route is too congested.

Traffic jams and its aggravation are part of my daily commute too, some of which I enjoy, and some I don't. Some people like to work in the car, if they have a driver. Others, like me, listen to news and music. Let me give you a glimpse of what I like about the commute, i.e., the consumption aspect of time spent in the car.

I get almost all my news updates, plus reality check on aspects of modern life, recent developments in the field of medicine, prospects for my retirement investment and the financial markets, and the latest on gizmos, from radio programs while I am driving. But, after an hour sitting in traffic listening to the radio, the law of diminishing marginal utility kicks in, further accentuated by the rising anxiety level as I notice that I'm going to be late for work again.

For the average commuter, the costs often outweigh the benefits of traffic jams. And for the society in general, when pollution, time lost, noise level, and reduced commercial activities are added up, the goal to rein in the monster of traffic congestion attains a higher level of priority. But unless we do it right, the prescription might be worse than the malady.

What triggered my reflections on traffic congestion and its ramifications are two recent news items that caught my attention. The first one appeared on the internet edition of The Daily Star on February 1. The headline story announced "Businesses to stay shut alternately." It continued: "In another move to ease traffic congestion in Dhaka, the government on Monday divided the capital into seven zones and fixed separate weekly holidays for shops, shopping arcades and other commercial establishments."

The other news item, first reported by the wire news agencies, relate to Mexico City, which will host the next Climate Change Conference in 2011. It has been able to dramatically improve its traffic and air quality in the short span of a decade. I remember that back in 1995, the traffic problem in Mexico City formed the core of a major case study.

So, I was quite surprised at the contrast that has emerged between the Mexico City of 1995 and 2010. What did Mexico City do that allowed it to reach this point? What can Dhaka learn from Mexico City? For the record, the average traffic congestion index (TCI) in Mexico City dropped by almost 50% during this time period.

There are two basic approaches to reduction in traffic congestion, incentive-based and regulation-based. Bangladesh, by restricting access to certain areas of the city on a rotating basis, or closing down shops during certain days and times is pursuing a regulation-based policy.

One of the problems with such an approach is that creative folks often find a way to avoid the regulation. For example, Mexico City adopted a policy whereby motor vehicles with odd-numbered license plate were ordered to stay off the road on certain days. The program, called Hoy No Circula ("not to run today", or "one day without a car"), was an attempt to cut down on pollution and traffic congestion. Unfortunately, this led many families to buy a second car, which was used on those "restricted" days. Mexico City put in place many other measures, including a public transport system and incentives to use the system, to cut down the number of cars on the roads.

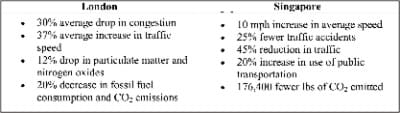

London and Singapore, on the other hand achieved significant drop in traffic congestions by using a slightly different, market-based principle. In 2003, London began charging a fee to drive into the city's congested business district, where traffic gridlock threatened the city's economic competitiveness and quality of life. A remarkable thing happened. The statistics in the following table speaks for itself on the impact of these steps on traffic congestion in the city.

Singapore was one of the first large cities to adopt congestion pricing, starting in 1975, with a $3 charge to enter the central business district during morning rush hours. Other charges and a second cordon area were added later. Singapore's success in creating a traffic-free environment and improvement in the quality of life in the city state is phenomenal.

I end with an example to illustrate the cost of time lost in traffic jams for a Dhaka City commuter. For hypothetical purposes, let us consider the scenario where one has to commute from Uttara to Motijheel or Mirpur to Tejgaon. Whether you are going by car, CNG or bus, these trips do not take long on Fridays, when there is less traffic.

How much time does an average commuter lose every day? I asked my cousin who lives in Baridhara and goes to work at Bangla Motors. During the day he also makes trips to other places. However, I am just focusing on time lost in commuting.

If a person loses 15 minutes a day and estimates that s/he could have earned an extra Tk.1 an hour, each month s/he loses Tk.300 in missed earning opportunities. This goes up to Tk.1200 if the time spent in traffic is one hour a day. When you sit in traffic, the cost adds up!

This simple exercise shows that (a) the cost of traffic congestion can soon add up, and (b) a policy based on fees may offer some benefits, at least better public transportation and other urban planning measures kick in.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments