A tradition navigating towards extinction

The models on display are handcrafted, maintaining every single feature and detail of each type of boat. Photo: Mumit M.

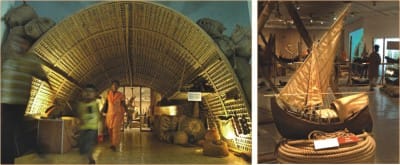

As you walk into Nalinikanta Bhattashali Gallery, National Museum, you find yourself under a chhoi (bamboo roof) of an actual Patam boat. The chhoi is as big as a living room -- with a clay stove, provisions, cargo of jute and tea boxes, knick knacks and essentials that may belong to boatmen -- giving you an idea of how big (around 70 feet) this now-extinct boat was. A Patam boat could carry cargo weighing up to 1000 maund (approximately 40 tons).

Fifty miniature and a few life-size models of traditional Bangladeshi boats are on display at the museum. The exhibition has been organised by Friendship and sponsored by AB Bank. Formed in 1998, Friendship is an organisation that identifies and tries to reach out to the most vulnerable and marginalised communities.

The ongoing exhibition at the museum is part of Friendship's Cultural Preservation Programme that intends to conserve the heritage of boat building in Bangladesh and facilitate socio-economic development of the craftsmen and their families involved with this tradition.

The models on display are handcrafted, maintaining every single feature and detail of each type of boat. The exhibition also houses materials traditionally transported by these boats. Bales of jute and rope, bamboo and earthenware give a sense of what life on a boat is like. Films projected and descriptive panels provide further information on these boats.

From time immemorial boats have been a major mode of transport in the Bengal delta. While sea-going vessels adopted exotic styles influenced by foreign trade, wooden boats of the inland waterways developed their shapes and forms according to indigenous needs. These boats were built using skills and technology that have been passed down from generation to generation.

Until the mid-20th century, these riverboats of Bangladesh remained the same. Around the 1980s two technological revolutions occurred, suddenly changing the riverscape -- from a sea of colourful sails to a bare noisy one. With the advent of cheap diesel engines the first revolution was the rapid motorisation of boats. The second was the change of boat-building material -- from wood to tin and welded steel sheets. Traditional wooden boats soon became too expensive and economically less viable.

These alterations are ushering in an end to a magnificent heritage, changing the lives of families involved with this craft.

The exhibition has been meticulously planned and organised -- providing details on each kind of boat. Thanks to the panels accompanying the models, the viewers get to know that a Dinghy (from Pabna) boat is 5.5-7.6 metre long and 1.5-1.8 meter wide and a Bazipuri (from Barisal) is 12-15.2 m long and 3-3.6 m wide. The latter, with two trapezoid shaped sails, has its chhoi in the back and is now extinct. The kosha (from Pabna) -- 7.6-9.1 m long and 2.4-3.35 m wide -- stands out for its flat hull and is used to travel short distances. Palki (from Chandpur) -- 9.1-12.2 m long and 3-4 m wide -- was a beautiful specimen of craftsmanship for its ornate golui (front and rear end of a boat). "Was," because it's now extinct. Potol (from Faridpur) -- 9.1-15.25 m long and 2.3-3.8 m wide -- perhaps gets its name for its resemblance with the vegetable; the chhoi extends all the way to the back. The Shampan (from Chittagong, Cox's Bazar and Mongla) tread the mighty waves of Bay of Bengal and can carry up to 100 tons of cargo. The distinct shape of the boat -- 12.8-14.65 m long and 4.6-5.2 m wide -- has a Chinese influence.

Also on display are models of Pinash, Bajra, Basari, Goina, Donga, Tedi Balam, Shuluk, Mayur Pankhi, Goghi and many more.

A skeleton of a large boat is put on display as if to caution the viewers what the future of our traditional boats might look like if the nation does not set its focus on this heritage.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments