Food for thought

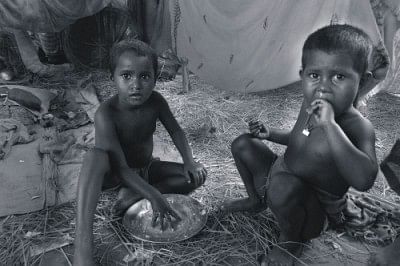

They are deprived of food, the nation of a resource. Photo: Monirul Alam/ Drik News

EVERY year over 20 million children in the developing world die from malnutrition -- the single biggest contributor to child mortality. Today, the number of undernourished people in the world is close to one billion, and nowhere is this problem bigger than in South Asia.

Astonishingly, 45% of South Asian children are undernourished. Both underweight and stunting (short height for age) rates in the region are much higher than that of anywhere else, including Sub-Saharan Africa.

Nearly a decade of robust economic growth has just not translated into improved nutritional status for children in South Asia, and sadly no country in the region is on track to meet the nutrition Millennium Development target of halving the prevalence of underweight children by 2015.

Although Bangladesh made significant progress in reducing under-nutrition in the 1990s, this progress has slowed noticeably since 2000. The most alarming trend in the country is the level of acute under-nutrition, or wasting, which increased by more than 50% from 2000 to 2007.

Clearly, these shocking and puzzling statistics demand stepping up of both analytical work and experimentation with new approaches. Therefore, in an attempt to raise awareness and arm people and policymakers with information that can help transform nutrition programs and policies, the World Bank and partners, including Unicef, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, World Food Programme, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition, and PepsiCo, are hosting a South Asian Development Marketplace (DM) competition that will support innovative approaches to addressing the problem of child under-nutrition.

The impact of poor nutrition can be devastating and is largely irreversible. A child who was undernourished during its first two years of life is less likely to complete school and will earn on average 10-17% less than one who was well-nourished. The economic costs, too, are substantial. A World Bank report estimates that malnutrition is costing poor countries up to 3% of their yearly GDP.

Leaving aside those statistics, the endemic perseverance of under-nutrition in the region is simply unacceptable. It robs a child of a chance to succeed and live a healthy, productive life. And it can be prevented -- with the right actions and the right commitment.

Contrary to popular belief, putting more food into the mouths of children cannot overcome under-nutrition. In fact, many children living in households with plenty to eat are still underweight or stunted because of misguided infant and young child feeding and care practices, poor access to health services, and poor sanitation.

Furthermore, aggregate national nutrition indicators mask vast disparities between rich and poor and people living in urban and rural areas. For example, in Bangladesh, stunting is most common in the poorest households where more than 50% of children are too short for their age, compared to only 26% in the wealthiest households. Stunting is also more prevalent in rural areas (45%) than in urban areas (36%), and among children of uneducated mothers.

So what can be done to improve the nutritional status of South Asian children? First, it is important to recognise that under-nutrition's most damaging effects occurs from just before a woman becomes pregnant to the first two years of the child's life. There is broad agreement that the damage to physical growth, brain development, and human capital formation occurring during this period is extensive and to a large extent irreversible.

Hence nutrition interventions need to focus on this narrow window of opportunity.

Pregnant women also need more attention, especially in South Asia. Around one-third of all children born in South Asia are of low birth weight, compared to 15% in Sub-Sahara Africa. Low birth weight indicates that a child was undernourished in the womb, or that the mother was undernourished during her childhood or pregnancy. This is reflected by statistics showing that over a third of adult women in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan are underweight, and the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia ranges between 55-81% across the region.

At the South Asia Development Marketplace, 60 civil society and grassroots organisations from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka will display their ideas in Dhaka on August 5 on how to improve nutrition to pregnant women, and to infants and young children during their first two years of life.

The goal is to encourage, showcase and learn from innovative approaches that can be incorporated into national nutrition strategic planning and programming. We expect this event to highlight the need to empower women within their families and communities in order to address the socio-cultural determinants of under-nutrition, increase access to and use of micronutrient-rich foods or supplements, and change household behaviours to address child under-nutrition.

We hope it will help reposition nutrition to the centre of development so that a wide range of economic, social, and environmental improvements that depend on nutrition and nutrition depends upon can be realised.

After all, there is an urgent need to build a strong, healthy and well-nourished population that can make the most of education and employment opportunities available in today's rapidly globalising world.

We have seen that developing countries that invest in better nutrition for their children get high returns on their spending. Good nutrition can drive economic growth rather than riding on the coat-tails of economic growth because children who are well-nourished are much less likely to be sick, more likely to go to school, less likely to drop-out, and more likely to learn better and develop to their full potential.

Well-nourished children represent strong human capital and, in these times of crises, it becomes even more critical to build this human capital to protect countries against future shocks. The World Bank is committed to helping countries to build their human capital -- the time to act is now.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments