Let's generate clerkship institution

Bengali educated class have typical aversion to the word “clerk” and the class it denotes, so to appease their anxiety we would like to clarify at the beginning that, contrary to the word “clerk” is used, law clerks do almost no clerical jobs. The institution of law clerkship originally developed in the United States. In 1882, US Supreme Court Justice Horace Gray appointed a new law graduate as “secretary,” and almost instantly the practice was greatly welcomed by other judges and these secretaries—later termed as law clerks—have become indispensable to the US judges ever since. They are bright young men and women in their 20s, fresh out of the top law schools, trained in cutting-edge developments in the law, provide research assistantship to a single judge mostly for one or two years.

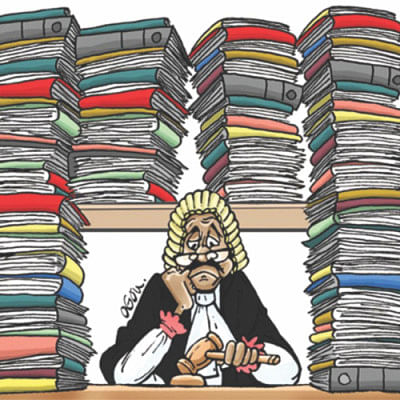

The most compelling reason for the exponential rise of clerkship institution in American courts—and later in other countries' courts was the increasing workload during the industrial growth occurring at the late nineteenth century. By doing the “drudgery of judging,” law clerks helped the judges effectively reduce their judicial time invested in every case. With almost 2.9 million pending cases, Bangladeshi judiciary has been suffering from a colossal caseload. The bleak side of this statistics is that in 2.9 million cases, justice is pending. Our judiciary has considered a multitude of strategies to tame this monstrous caseload, even making the number of judges “at least double” has been expressed in a “five-pronged strategies” by the Honorable Chief Justice Surendra Kumar Sinha. But no one ever considered introducing the clerkship institution which is an effective antidote to caseload in many countries. Mr. Chief Justice offered a statistics that if all administrative business and meetings are not held during office-hours, backlog of cases will be reduced “by an extra 10%.” But if we offer extra time to Judges' by providing them two law clerks, how much backlog will it reduce?

Though we cannot precisely fathom the backlog that law clerks could reduce if we introduce the institution in our judiciary, we can inform our readers what duties they perform in the court of other countries. The duties and responsibilities of law clerks depend on multiple factors, such as the court, the judges, and even on the season of the year. But universally law clerks perform research and related works. They read case files, prepare case summary and notes, chronology of events, find legal questions in the fact, search for case laws, articles, papers and other materials, sit in the court during hearing and take notes of arguments, crosscheck the references used in judgments, and any other job his judge may entrust upon him. Sometimes they help the judge prepare speeches and academic writings. By doing these, they save valuable time of a judge, and thus, by saving their time—to rephrase the old adage—law clerks save the judges' lives.

In contrast, a bulk of the time of our judges' life is spent in doing research work for each individual case, especially in appellate cases. They alone have to perform all of the tasks we mentioned above, which is, to say the least, a waste of judicial time. On this count, our judges are falling behind their counterparts in India and Pakistan where law clerks successfully provide research assistantship to judges in both Supreme Court and High Courts. In India, law clerks are called “law clerk-cum-research assistant,” who are selected through a highly competitive National Level Written Examination. In Pakistan, the system is taken to be a policy of “inducting fresh blood into the system.”

As clerkship is a performance-based job, the demand for better performance will eventually push law schools and related institutions into pressure to ensure quality education. When law school produces skilled graduates, it is obvious that these graduates as law clerks will keep our court abreast with cutting-edge research into law.

Now we will consider two important arguments that may arise against clerkship institution. Firstly, a legitimate question regarding the quality of law graduates—from whom law clerks are to be selected—can be raised. We argue that in every year we appoint assistant judges from these same young men. If we appoint them as judges, then why not as law clerks? As a clerk, they are not writing judgments, they are just providing research assistance to the judges. Secondly, it is a concern that law clerks may influence judge's decision and the legal process. We do not deny that there is truth in the objection. But law clerks being like the apprentice in Goethe's The Sorcerer's Apprentice, the scope of their influence in judgment as well as legal process are limited. Apprentices can do many things on their own, but can never go beyond their master, in our case their judges.

A robust clerkship institution can be the better cure to our judiciary's caseload problems. It can also be a good help to our judges—the “lone rangers” in our fight against injustice.

The writer is a Lecturer of Law, Z. H. Sikder University of Science and Technology, Shariatpur.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments